This article was originally published on August 30, 2023.

It’s hot. It’s the end of August. You make your living running around outdoors in this weather. You don’t really get weekends. You’ve been living out of a suitcase for the last five months. You’re tired. The dog days of summer have arrived and you don’t wanna anymore. Well, you do, but it’s hard. There’s a lot that happens during the day of an MLB player, and yes, I know that even the minimum salary ones make $700,000. Those are still hard working conditions and they happen day after day after day after day after day. Every day, you need to find something to keep you going and something to keep you sane. Some players are just naturally motivated like that, but for those who aren’t, something or someone needs to be that motivating force. Welcome to The Grind.

Every once in a while, I have a moment where I remember an old article that I wrote – and it always goes like this in my head – “a couple of years ago.” Except that it always turns out to be 7 or 8 years. So… in 2015, I looked at the question of whether some managers seemed to have an ability to fight against The Grind. It turned out that the answer was “Yes” and… it was worth a lot.

Managers have a rough job. We mostly think of what they do between 7 and 10 pm. They are the button pushers and the tacticians of the team. It’s just that tactics aren’t actually worth all that much to a team. Most of what we call “strategy” in baseball boils down to a few plays that aren’t called very often and only provide a bit of value here and there. But managers do so much more between 10 pm and 7 pm. It might not be the manager who does this, but it’s the manager who selects the coaches and the manager who needs to be aware of how each of the 26 players are doing. Not just on the field, but how they are “doing” as humans. It’s the manager’s job to make sure that all of them are prepared for that night’s game and they are fighting against the realities of The Grind. Sometimes that means a rousing speech. Sometimes it means a quiet conversation with someone. Sometimes it’s just knowing when to give a player the day off.

After looking at the date stamp from last time, I wondered how things have been going. Last time, I identified managers who were really good at fighting against The Grind and some of them are still managing. I got to wondering whether they were still good at it.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

So first, how do we even figure out if players are suffering from The Grind? I started with the idea of plate discipline. I settled on a simple definition of plate discipline which is that “strikes are bad” which isn’t a perfect definition, but it serves our purposes, and strikes really are bad.

The reason I thought of plate discipline to start with was that what we call The Grind is likely the effects of constant travel and sleep deprivation compounded over weeks and months. When the human body is deprived of sleep – not staying up all night deprivation, but the slow drip of “I got five last night” – the effects start first on more complex cognitive processes. Pattern recognition, visual-spatial reasoning, decision-making, those sorts of things. Those are the skills that play into the split-second ability a player has to pick up on a ball coming in at 98 mph, figure out where it’s going, make a decision on whether or not it’s a good idea to swing, and then initiate the swing motion. In other words, plate discipline.

Using data from 2018-2022 (I left out 2020, because 2020 never happened and the compressed schedule from that season messes everything up), I coded all pitches in MLB games based on whether or not they produced a strike. I also coded, for each game, how many days it had been since Opening Day.

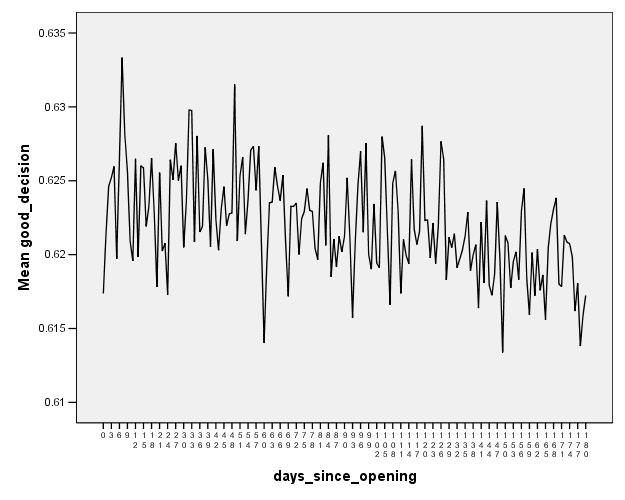

In the 2010-2014 data set I used in my article from several years ago, I found that as the number of days went along, batters made slightly worse decisions. Here’s the graph for the league overall in 2010-2014.

It’s the sort of thing that wouldn’t be visible to the naked eye, but over a lot of pitches – and the average team sees 150 pitches per night — it might turn a couple per week from a strike into something that’s not a strike (a two-strike foul, for example, would count as “not a strike.”) And turning a strike into a “not a strike” is worth a lot, about a tenth of a run per converted pitch. And we can see a small downward trend as the seasons go on.

In 2015 (and I updated the work in my 2018 book The Shift: The Next Evolution in Baseball Thinking), I looked to see whether some managers were able to bend that curve back upward. Or at least slow the rate of deceleration. It turns out that the answer was “yes” and the results suggested that managers maintained their ability (or lack of that ability) to bend the curve over several years. The effect size was big enough that a good manager on this Grind prevention measure was worth a couple dozen runs more than a bad one.

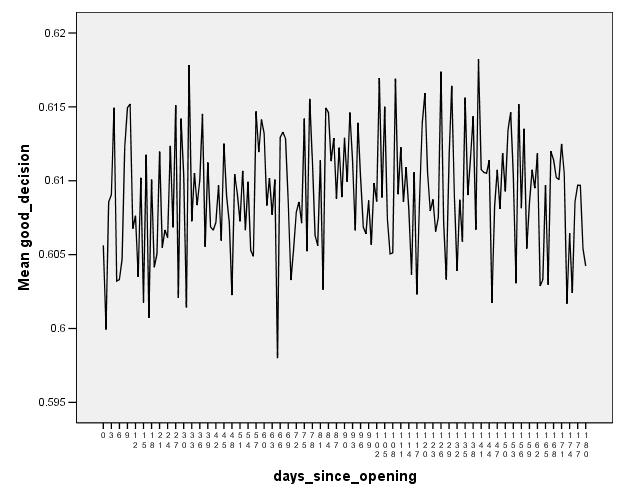

My initial goal when I started writing this piece was to see which managers had been doing the best lately, but when I ran that “here’s the basic pattern graph” for the 2018-2022 season, I got this:

Where’d The Grind go?

There’s no question that baseball remains a very grinding sport, but in the last few years, we’ve seen and heard teams taking that seriously in new ways. The Red Sox built a nap room at Fenway Park. Teams have re-thought their approach to mandatory batting practice. For some players, it’s just another thing that they have to do, and if it isn’t going to help, why waste the energy? Or if rest is the more pressing need, why not tend to that instead? The phrase “load management” has entered our collective baseball vernacular.

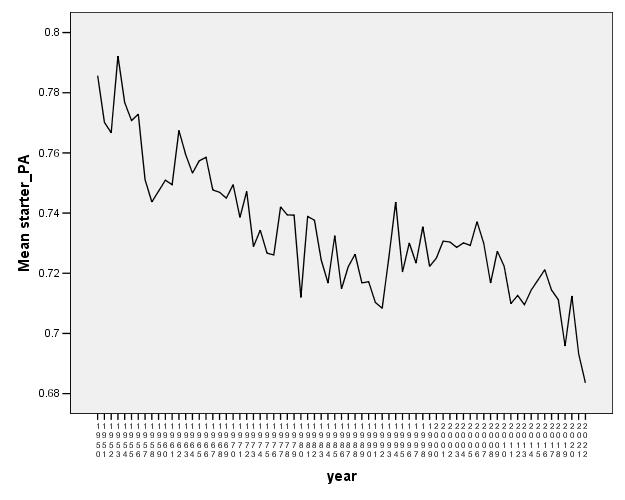

Teams have become better (and have become better able, through expansions in the talent pool) at giving their regulars more time off. This graph shows the percentage of plate appearances in each season taken by that season’s “starters,” defined as the (8 * number of teams in the league) players who had the most plate appearances that year. A higher percentage shows that teams were concentrating their playing time in their regulars, while a lower percentage shows that they got a few more days off and the bench bunch got more playing time.

There’s been a pronounced downturn over the last 10 years and particularly over the last five. It’s a trend that we see in a lot of graphs where in the last 10 years; there’s been a change in how teams approach many strategic elements of the game. A lot of the time, it’s been around finding “market inefficiencies” in what is effectively toxic cultural messaging. There’s a leftover idea that players should strive to play 162 games per season, despite the fact that humans are not pack animals. They need rest. As teams have come to realize this more and more and take it seriously, they’ve gotten a benefit.

Since I’m plugging my books today, I’ll point out that in my recently released The New Ballgame: The Not-So-Hidden Forces Shaping Modern Baseball, I looked into the issue of “starters” getting less playing time, along with other strategies like teams developing multi-position players so that they can be more modular in their lineup construction. As teams have embraced these strategies, they haven’t been using them to get more platoon advantages for example. It seems like it’s mostly about the rest and relaxation it bestows on the players. And the numbers say that’s a good choice.

Recall a few moments ago when I said that when I looked at this issue in 2015, I found that there were certain managers who seemed somewhat consistently capable of keeping players from sliding into the doldrums of summer. I estimated that the spread from worst to first among managers was a couple dozen runs. That’s a big prize to be claimed if a team can figure out how to do it, and that’s just the benefit that players get in their plate discipline from being better rested.

One of the features (or bugs, if you prefer) of the last decade of baseball has been the homogenization of strategies. As teams have studied load management, they’ve implemented policies that have promoted more rest. There is a cost to resting your players. Someone from the bench has to play instead, and the reason they’re on the bench is because they aren’t as good, but if you can trade a small downgrade today for a better performing star later in the season, you can come out ahead in the long run. As more teams do that math, the game has tilted more toward seeing rest as a strategic advantage.

As for the managers, there are probably plenty of ways that they do help to motivate players behind the scenes and keep them sharp and motivated, even in late August. And even if the policy is “give the players more frequent days off”, it’s an art to know when someone needs a breather and to match that up with a day where the matchups are favorable to allow for that day off. But when I looked to see if any of them had a special ability to arrest the effects of The Grind on plate discipline, as I found in the 2010-2014 data set, I found that the manager-specific effects had largely disappeared. More generous resting policies seem to have taken over.

The idea of rest as a strategic advantage seems to be making its way into the heart of the game. It’s happening among pitchers as well, as a model of sharing the pitching workload has developed, in part because pitchers show that sort of wearing down effect as well over the course of a season. And… in a sport that still reveres Cal Ripken for never taking a day off for a decade and a half, that’s going to be a little contentious. Strategy is often quicker to change than culture. We are living through a strange and turbulent time in baseball, even if that turbulence is caused by players sitting quietly for a day. Sometimes we all need to do that.

The post Best of BP: The Dog Days Are Over appeared first on Baseball Prospectus.

https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/87452/best-of-bp-the-dog-days-are-over/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions