Gregory Fisher-USA TODAY Sports

I like to amuse myself by imagining a scenario in which Brad Pitt’s Billy Beane has to replace a departing Juan Soto. Now, if Moneyball came out in the 2020s, Soto would’ve been traded years ago and Jonah Hill’s Peter Brand would be heroically figuring out how to procure a block of taxpayer-funded stadium-adjacent condos for Steve, the cheapskate owner. But it’s my imagination, so it doesn’t have to be that bleak.

This is a kind of reverse-Six Million Dollar Man scenario: “We have to rebuild him; we don’t have the money.” Soto doesn’t provide any special value in the field or on the bases; even the cheapest team in the league can find an unremarkable defensive corner outfielder who steals 10 bases a year. The tricky thing about finding a poor man’s Soto is replacing his ability to get on base.

Guys who run a .400 OBP, or a walk rate in the high teens, are rare but not unique. Especially if you exclude those high-OBP guys who also bat near .300 and have 30-plus home run power, the tools that price the imaginary A’s out of Soto’s market. (Or Bryce Harper’s or Aaron Judge’s or Kyle Tucker’s.)

For about a year now, my answer to the question of how one would go about Hatteberging Soto’s Giambi has been LaMonte Wade Jr., the Giants’ first baseman. Wade leads all of baseball with a 21.4 BB%; having drawn only a single intentional walk this season, Wade’s unintentional walk rate is less than two points below Barry Bonds’ unintentional walk rate in 2001 and 2004. (Anyone who walks that much in a city as hilly as San Francisco must have calf muscles the size of rugby balls.)

Wade’s has only homered twice in 2024 as of this writing, and his ISO is only .111, but if he could hit for power he’d be making $30 million a year too.

Let’s lower the plate appearance threshold a little, to 90. No. 2 on the walk rate list is DJ Stewart, who according to Baseball Savant also has the lowest chase rate in the league. Stewart was a late first-round pick by the Orioles in 2015 out of Florida State, but never caught on with Baltimore even as the team languished in the 100-loss zone.

Stewart emerged as a part-time player with the Mets last year, and in this rebuilding year the 30-year-old has staked a claim to the long side of a DH platoon. Stewart is only hitting .205, but his walk rate, along with four home runs in 69 at-bats, has brought his wRC+ all the way up to 141.

Even in a quarter of a season as a platoon player, this is a pretty remarkable performance. Stewart was good when he played last year (.244/.333/.506 in 58 games) but he’s doubled his walk rate and cut his strikeout rate by a third. His chase rate — 25.8% last year and close to 30% for his career heading into this season — has fallen to 14.0%.

So before the Mets-Phillies game on Wednesday night, I asked Stewart what adjustments he’d made to bring all this about, to become the most selective hitter in baseball.

Stewart shrugged.

“I’ve always had a good eye,” he says. “I just feel good with my swing right now, and I’m really zoning in on where I want the ball to be. And if they’re not throwing it there, then I’m not swinging at it.”

Stewart’s right — he has always had a good eye. His college coach, the late Mike Martin, was famous for developing offenses that were absolutely miserable to pitch against; Martin’s teams were usually among the national leaders in walks and OBP, and as a result his Seminoles were good for 40 wins a year like clockwork. Stewart was Florida State’s standout hitter during his time in Tallahassee, and in his draft year — in an environment fairly hostile to offense — he posted an OBP of an even .500.

“It’s definitely something that’s preached at Florida State, to get on base any way you can, whether that’s drawing walks or getting hit by pitches,” Stewart says. “But at this level, you want to get on base, but you want to do damage as well.”

Stewart can do damage when he makes contact, but is very choosy about “his pitch.” Basically, anything up in the zone is no good. He’s still looking for his first hit this year in the top third of the strike zone. Anything in the bottom third of the zone is fine, but not great. But he demolishes pitches in the middle third.

DJ Stewart, Top to Bottom

| Zone |

AVG |

SLG |

wOBA |

Whiff% |

Pitch% |

| Top Third |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

44.7 |

16.3 |

| Middle Third |

.440 |

.880 |

.568 |

6.5 |

18.1 |

| Bottom Third |

.188 |

.438 |

.314 |

26.9 |

14.3 |

SOURCE: Baseball Savant

On pitches middle-middle, especially, Stewart is a menace. Like, everyone does damage on pitches over the heart of the plate, but even by that standard Stewart has been awesome this year. And he knows it. He’s seen 27 pitches middle-middle, swung 23 times, and missed once. Here are his numbers on those pitches, along with how they compare to hitters across the league.

I’m Trying to Get Down to the Heart of the Strike Zone

| Stat |

AVG |

SLG |

wOBA |

Whiff% |

| Value |

.533 |

1.200 |

.742 |

4.3 |

| Rank |

29th |

16th |

13th |

43rd |

SOURCE: Baseball Savant

Minimum 250 total pitches seen through 5/14 (329 players)

Still, getting literally nothing out of the top third of the strike zone isn’t great, and probably explains why Stewart is walking 20% of the time but is only hitting .205.

But one of the big breakthroughs in baseball analysis in the past year has been formalizing the idea of selective aggression: swinging at pitches you can do damage on and spitting on the others.

“I’m not up there trying to draw a walk, that’s for sure,” Stewart says. “I’m trying to do damage in my zone. And if they miss [my zone]? Take it and live with the results.”

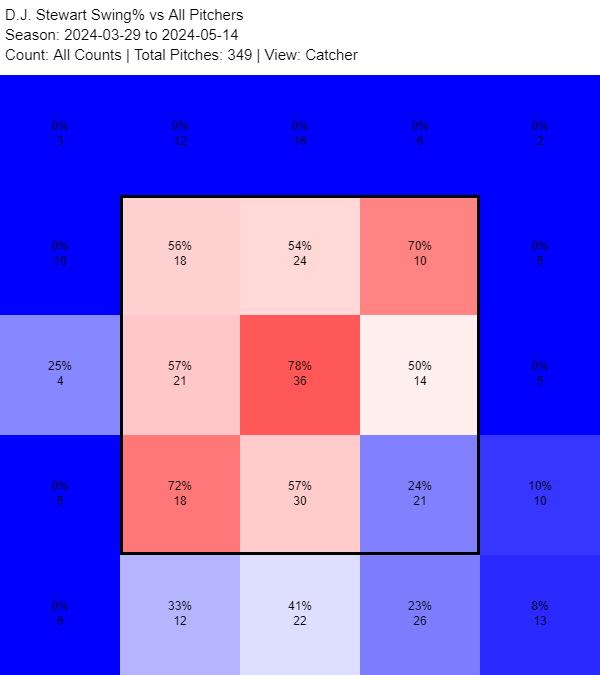

So with that in mind, here’s Stewart’s swing rate by pitch location.

He’s still swinging at pitches that beat him up in the zone, but outside the zone? Stewart just isn’t interested. Those squares are bluer than Cookie Monster’s backside.

Also, are you curious how a guy with a 19th-percentile whiff rate ended up with a 57th-percentile K%? I sure as heck was. Turns out that with two strikes, Stewart is only swinging at 3.2% of pitches outside the zone. That’s tied for the third-lowest swing rate among the 329 hitters who have seen 250 or more pitches this season. So that probably helps.

And because Stewart has exhibited such unusually good command of the strike zone, he’s played his way into a regular role, starting and playing a higher percentage of his team’s games than in any pervious season. Even though he’s only started a little over half the Mets’ games, Stewart says he’s very happy with the communication he’s gotten from manager Carlos Mendoza and the Mets coaching staff.

“Every year has a learning curve,” he says. “It’s a little bit different. But I think our manager does a very good job of communicating with us — situations [we might play and] who we might face if we’re not starting.”

On Sunday, Stewart got his second career start in an unfamiliar role: Batting leadoff. With Brandon Nimmo nursing side soreness, Mendoza put Stewart — who’s second to Nimmo on the team in walks — at the top of the lineup.

With the Mets playing the Phillies — a team that leads off its lineup with a hitter who batted .197 with 47 home runs and led the league in strikeouts in 2023 — I asked Stewart about it. As a stocky left-handed hitter who hits from a crouch, the more Stewart walks the more he starts to resemble a Kirkland Signature Kyle Schwarber.

Stewart replied that he’d batted first growing up, so he was comfortable at that spot even if he’s been more of a middle-of-the-order guy in the pros. He also took pains to stress that “we have a very good leadoff batter.”

But: “I don’t care where I hit. It doesn’t matter to me.”

In terms of lineup position, that might be true. But “where” — knowing where to swing and where to take — has been the key to Stewart’s season.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/dj-stewart-is-walking-here/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions