Nick Turchiaro-USA TODAY Sports

In 2021, Vladimir Guerrero Jr. put on a remarkable show, hitting .311/.401/.601 with 48 home runs. He finished second in MVP voting to Shohei Ohtani — perhaps the only drawback to having Ohtani in the league is he’s going to end up dwarfing about a decade of other great performances on the historical record — with a season that looks even better in context.

In the past 100 years, only 10 AL or NL players have posted full seasons with a .300/.400/.600 slash line at age 22 or younger. And this is not one of those things hitters tend to achieve before flaming out. Of those 10 players, five — Ted Williams, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Joe DiMaggio, and Eddie Mathews — are not only Hall of Famers but inner-circle Hall of Famers. Albert Pujols will be once he’s eligible. Alex Rodriguez would be if he’d stayed away from Biogenesis and/or not been so weird the entire sport had it out for him. That leaves three active players: Bryce Harper, Juan Soto (in the COVID-shortened 2020 season), and Vladito.

So that’s five Hall of Famers, three future Hall of Famers, plus one guy who would be in the Hall of Fame if performance were the only consideration. But what of the young Guerrero?

I was thinking about this recently, as Guerrero and the Blue Jays traded arbitration numbers. It’s the most expensive arbitration case left on the docket, as Guerrero filed for $19.9 million, with the Blue Jays coming in at a hair over $18 million. The discrepancy between the two is more than twice what Casey Mize — the former no. 1 overall pick whom the Tigers are taking to trial over the cost of a certified pre-owned 2019 Honda CR-V — is even asking for. The Blue Jays are conceding that Guerrero, who is still due another year of arbitration after this one, is worth what would be first-division starter money on the open market.

That’s not really what Guerrero produced last year. In 156 games, he hit only 26 home runs, with a batting line of .264/.345/.444 and a wRC+ of 118. Remember the 2019 Home Run Derby?

That guy had an ISO under .200 last year. TJ Friedl, the buntin’-est cowboy east of the Pecos River, did better. Guerrero’s full-season WAR, 1.0, is derived in part from defensive metrics that are so unkind to the young Guerrero I worry that they violate the terms of this website’s comment policy. But even the bat was underwhelming compared to the admittedly astronomical expectations Guerrero went in with.

So here we have — at the risk of startling the ghost of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hagel back into corporeality — two contradictory versions of Guerrero. On one hand, the supreme hitting talent, the combination of plus-plus hit tool and 80-grade raw power, who has shown that he can hit with Hall of Famers. This player would be two full seasons from reaching free agency in time for his age-27 season and, like Harper and Soto, ringing the bell for many hundreds of millions of dollars.

On the other hand: What if Josh Bell was short? A good player — absolutely a good hitter — but one who’d have trouble in free agency for the same reasons Rhys Hoskins is still without a home. A great designated hitter has huge value. A good DH? Eh, you can go without.

So what’s the problem? How is Guerrero suddenly merely a good hitter rather than a transcendent one?

The first thing to point out is obvious: For a guy who hits the ball as hard as he does, Guerrero is pretty earthbound. That means fewer hard-hit balls in the air, and by extension, fewer extra-base hits and home runs. We’ve known this about him forever, and while it’s a weakness, it isn’t a fatal one. If you can read this, you’re old enough to remember a time when Christian Yelich was hitting 40 home runs a year with a GB/FB ratio that made Tim Anderson look like Phil Plantier. For all the hype about launch angle over the past decade, there’s a point where you can hit the ball so hard the trajectory doesn’t matter very much.

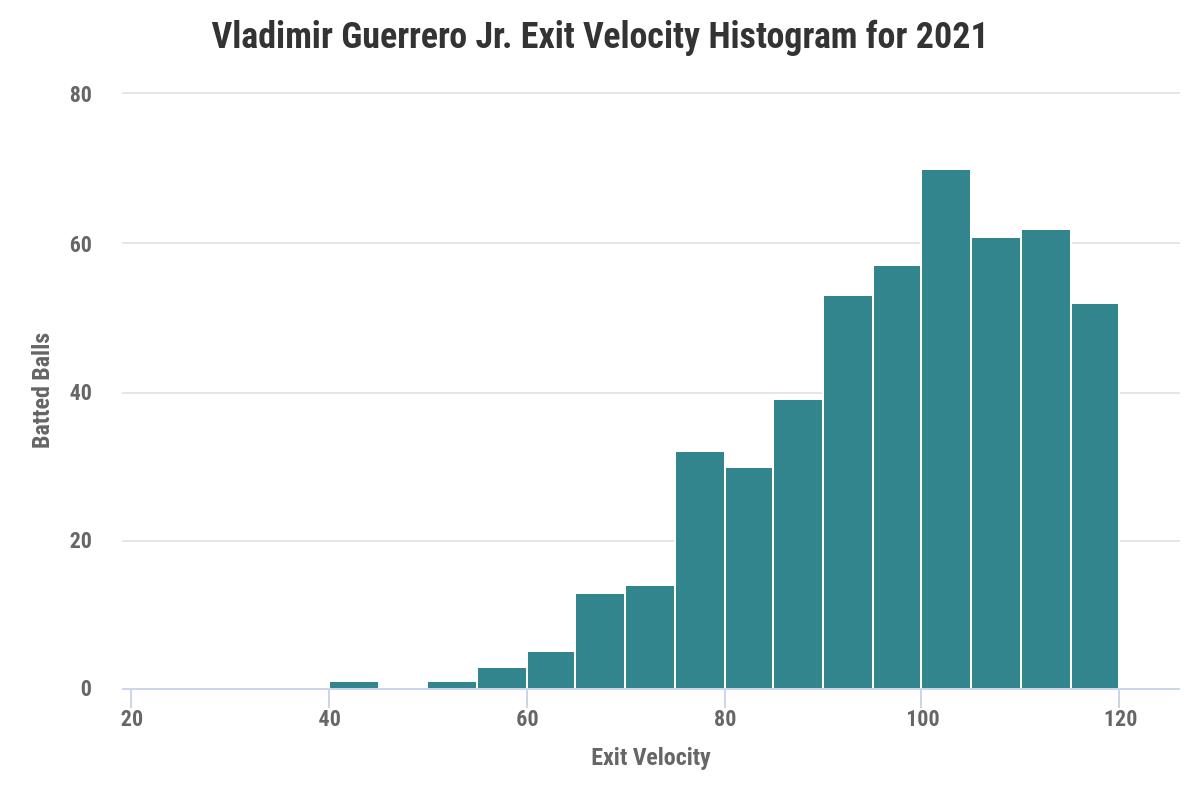

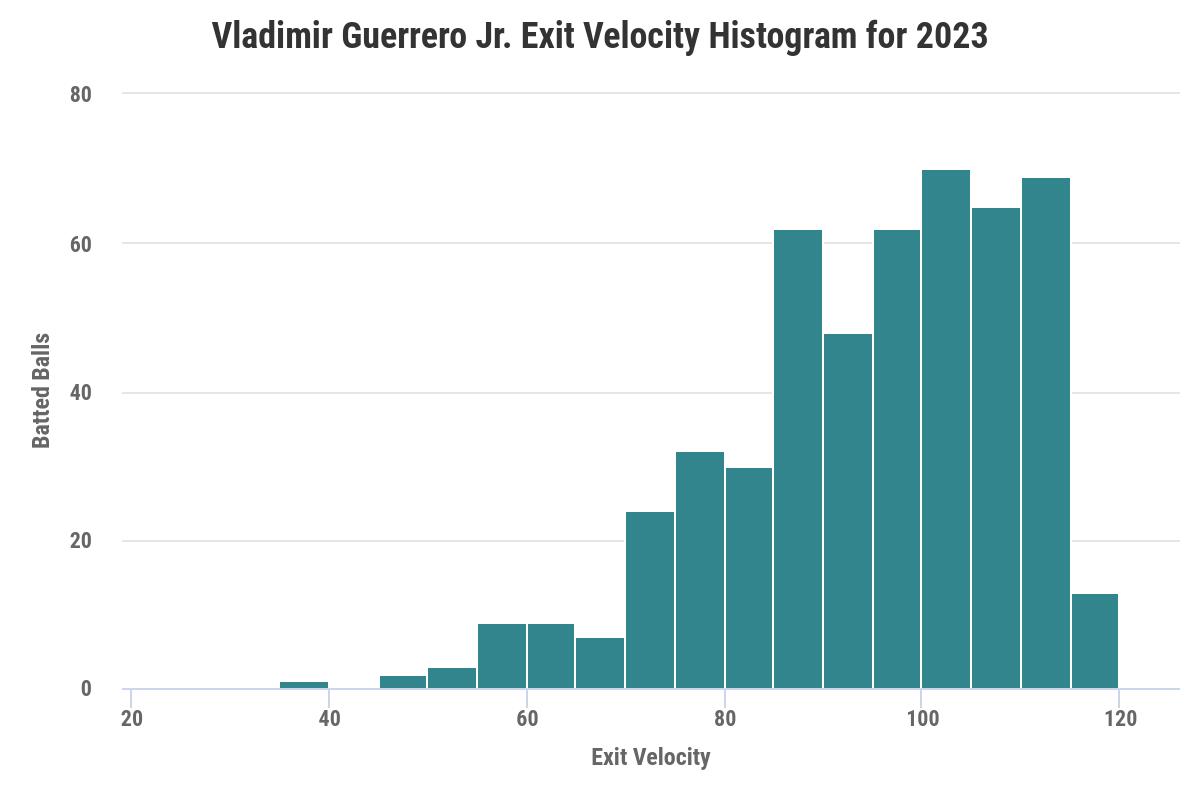

Which brings up problem no. 1: Guerrero didn’t hit the ball quite as hard in 2023 as he did in 2021.

See how far the right tail of this histogram goes, and compare it to 2023, which is still good but not top-five-in-baseball good.

It takes an outlier to buck a trend, and when Vladito was no longer regularly producing outlier exit velos, he was no longer able to buck the trend that groundball hitters put up less impressive power numbers.

Vladito’s Leaguewide Ground-and-Pound Ranks

| Year |

GB/FB |

ISO |

HardHit% |

| 2021 |

157th |

9th |

6th |

| 2023 |

212th |

125th |

30th |

Minium 300 PA (262 players in 2021, 293 players in 2023)

“Hit the ball in the air more!” I can hear you screaming, and that’s easier said than done. More than that, I wonder if Guerrero’s struggles (“struggles,” really; it bears repeating that in 2023 he was comparable offensively to Pete Alonso and Christian Walker) are the result of following what you might call the conventional wisdom when it comes to hitting.

Hear me out.

Vladito’s great strength is his ability to combine contact and power. In 2021, 20 qualified hitters had an ISO of .250 or better; of those, the young Guerrero had the second-lowest strikeout rate, just 15.8%. The only player from that group who struck out less was José Ramírez, and I just read somewhere on the internet that Ramírez is “a marvel.” “Contact” is probably not the right way to put it; in 2021, Guerrero had the 28th-lowest strikeout rate among qualified hitters but the 94th-lowest contact rate.

Bringing this back up is making my eye twitch, but down here in the Delaware Valley, we had some Discourse last fall. The Phillies, led by Harper and Kyle Schwarber, spent the first two and a half rounds of the playoffs ambushing opposing pitchers back to the stone age. When the bats went quiet in the second half of the NLCS, that same approach — which had looked unstoppable earlier in the week — got blamed for the collapse.

I bring this up because Guerrero is doing exactly the kind of evolved hitter stuff these critics want all modern sluggers to do. He doesn’t strike out much. He doesn’t uppercut to get the ball in the air. He hits the ball hard to all fields.

And he’s worse off for it.

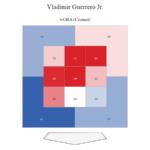

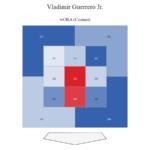

In 2023, Vladito had the highest contact rate of his career. In 2021, he had a huge hole in his swing at the bottom third of the strike zone, and in the past two years, he’s closed it; 2021 is on the left, 2023 on the right, from Baseball Savant.

So he’s making more contact, which is great in theory. But getting the bat on the ball isn’t the object of the game.

Guerrero is making more contact in parts of the zone where he doesn’t do as much damage. He’s also making more contact on pitches that are outside the zone altogether. His O-Contact% in 2021 was the lowest of his career, and the best part of nine percentage points lower than it was in 2023. Contact on these pitches turn into outs, or worse, double plays.

Nobody needs to be reminded of the perils of the hard grounder less than Vladimir Guerrero Jr. As a right-handed batter who hits the ball extremely hard on the ground and runs the bases at a spirited andante, he was built in a lab to hit into double plays: 92 of them since his debut, the second-highest total in the majors in the past five seasons.

In 2021, Guerrero was making the most contact in the upper two-thirds of the strike zone, which also happened to be the area in which he did the most damage. Now, he’s covering more of the zone but at the cost of making much less effective contact everywhere.

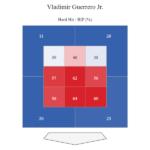

Here’s his wOBACON by region of the strike zone, again with 2021 on the left and 2023 on the right.

The 2023 heat map is just depressing to look at. It displeases me. Let’s move on.

What happened over the past two years, at the risk of oversimplifying things, is that Guerrero traded quality of contact in his kill zone for quantity of contact everywhere. You want to know why his HR/FB rate dropped from 26.5% in 2021 to 14.5% in 2023? Because his home runs come on hard contact up in the zone, and this happened.

And Guerrero’s groundball rate is only one of two directional concerns to his offensive game that required an outlier performance to overcome. As you’re no doubt aware, baseball stadia tend to have deeper outfields in center than down the lines. Vladito hits a lot of fly balls to center. When the ball is coming off the bat at 110 mph, it gets out. When it’s hit at 100 mph, it gets caught. And that spray tendency absolutely killed him in 2023, as Ben Clemens wrote in September.

A true dialectical examination of Vladimir Guerrero Jr. would attempt to resolve the contradiction between the harder-hitting 2021 version and the better zone coverage we saw in 2023. To hell with that — I say throw the measured 2023 approach in the oubliette altogether. If anything, 2021 wasn’t extreme enough.

The most remarkable thing about Guerrero, as I’ve said, is his minuscule strikeout rate for how hard he hits the ball. But a low strikeout rate is not an end in and of itself. It’s a gift. It means he has room to play with, to come out of his shoes swinging at pitches up in the zone, to swing and miss more, to cheat and clear his hips early — if it means restoring that exit velocity in the 110s. Aaron Judge and Shohei Ohtani are the two highest-paid batters in baseball, and two of the hardest-hitting. Both of them strike out almost twice as often as Guerrero does.

So if Guerrero wants to get paid properly, to return to that Hall of Fame path, he needs to stop trying to hit everything and get back to hitting fewer pitches harder.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-new-vladimir-guerrero-jr-is-holding-the-old-one-back/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions