A pintail hen takes flight over a marsh pond. R. Jeff Huth / Adobe Stock

As hunters and bird watchers track the waterfowl migration each year, many of them look up to the clouds of southbound birds and ponder: How far can ducks migrate in a day? Earlier this month, a pintail hen gave us an answer. She was sitting on a puddle in eastern Russia when she got the urge to fly back to her home continent. With the wind at her back, she took off at approximately 10:30 p.m. and was soaring over the Bering Sea by midnight. Reaching ground speeds of up to 150 miles per hour, the hen stayed airborne over southeast Alaska and the North Pacific. Twenty-five hours and roughly 2,000 miles later, the duck finally touched down in a wetland somewhere in northern California.

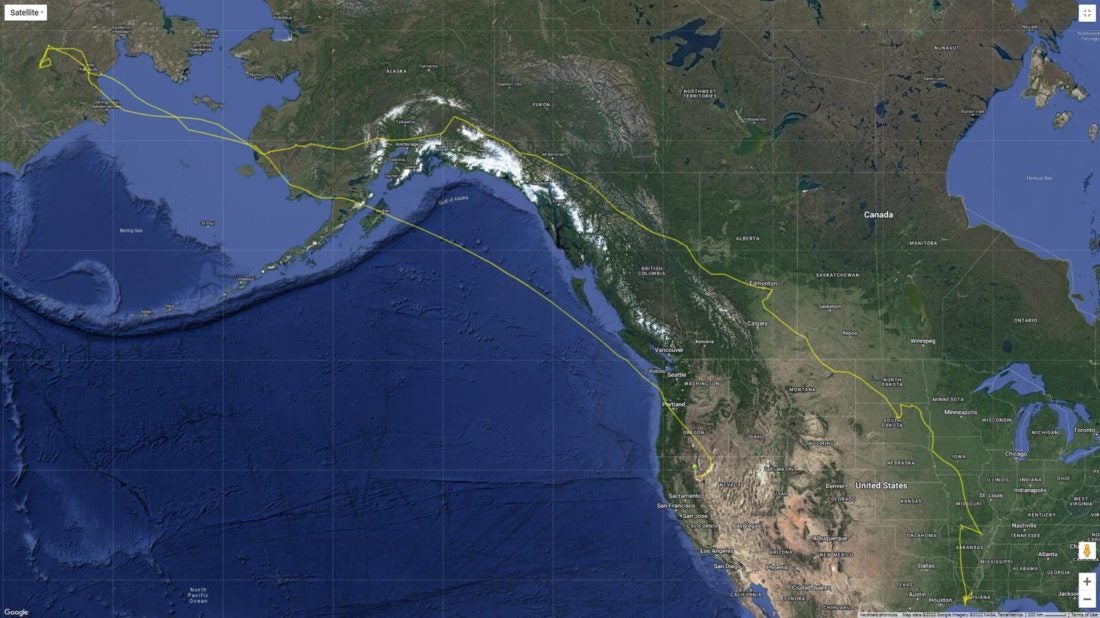

The bird had traveled approximately 10,000 miles over the last 10 months, and her journey wasn’t over yet. The hen’s final leg will carry her across the Pacific and Central Flyways all the way to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, where she was originally tagged by researchers in January.

“It’s unbelievable,” says Paul Link, a lead waterfowl researcher with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. “It’s the first bird I’ve ever seen do this. We’re way over here in the Southeast, and most pintails don’t cross three flyways like that. Certainly, to my knowledge, none of them have ever crossed into a different continent.”

But she’s not the only duck to make such an epic migration. Days after Link pieced together one pintail’s journey, he saw that another tagged pintail hen had taken a similar route, flying all the way to Russia and back. He says that bird is currently up around Great Falls, Montana, and he expects the two hens to head back to Louisiana any week now.

These two examples are cases of extreme long-distance and high-speed migration. According to Ducks Unlimited, most waterfowl fly at speeds of 40 to 60 mph, so with a 50 mph tail wind, ducks could travel approximately 800 miles during an eight-hour flight. Typically, a mallard would have to feed and rest for days after such a journey. However, new tracking technology is giving us an even better picture of how far ducks migrate—and why they might be going such long distances.

Using New Tech to Track Birds

Link has been studying waterfowl migrations for the last 14 years or so. Formerly the management coordinator for LDWF’s North American waterfowl management plan, he now works full-time as a researcher for the agency. He says this will be his fourth year in a row tracking pintails, but over the years he’s worked with nearly every waterfowl species from specklebellies to blue-winged teal.

Link says advancements in transmitter technology have ushered in a new era of waterfowl research. After years of using traditional, backpack-style transmitters that weigh about 15 grams, he was able to get his hands on lighter, 10-gram transmitters last year. The devices feature small solar panels that keep them charged for long periods at a time, and a couple have even functioned over multiple migrations, he says. The small size of the transmitter allowed Link to experiment with a new attachment method that is less cumbersome for the birds.

A pintail hen is fitted with a new, lightweight transmitter in LDWF’s lab. courtesy of Paul Link

“It’s basically like a skin piercing that holds the transmitter on their backs,” Link tells Outdoor Life. “There’s no harness or traditional neck-and-body loops like most transmitters we’ve used in the past.”

Also, unlike old-school transmitters that use VHF technology and require researchers to actively search for signals, the new, lightweight transmitters rely on GPS-GSM technology and use cellular networks to transmit data in real time. This means that as long as the bird is close enough to a cell tower, Link can see its location on an hourly basis, along with other information such as the bird’s heading and flight speed.

Working with graduate students this January, Link was able to fit 30 pintail hens with these new transmitters using his new attachment method. He also fit another 27 pintail hens with the slightly heavier, backpack-style transmitters. All 57 birds were captured in Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge on the southwest coast of Louisiana.

Over the course of this spring, Link and his students kept track of these green dots as they headed north toward the Prairie Pothole Region, which is where most of the continent’s pintails nest every summer.

“It’s my daily ritual,” Link says. “The first thing I do in the morning and the last thing I do at night is look at the control panel and see where all the birds are.”

When he logged onto his computer in late April, one of the green dots had vanished. This wasn’t unusual, and he explains that in his experience, only 50 percent of tagged pintails tend to survive from year to year. (He also admits that fitting them with transmitters doesn’t exactly help their odds of survival.)

“This particular bird went offline in southeast North Dakota in late April, and from there we just assumed the worst,” Link says. “By the time we get to the first of October, you’re thinking that bird probably got killed on her nest and is in a badger hole or a fox den.”

He was wrong.

To Russia and Back

Link isn’t entirely sure of the date, but sometime between Oct. 2 and 4 he saw that one of the transmitters had come back online. It was sending a signal from somewhere in northern California. He figured the duck had been killed by a hunter.

“I’m like, oh boy, that can’t be good. It probably means that someone from California went to the Dakotas and shot her,” he says. “But I clicked on the dot and saw that it was one of the pintails. I clicked the link, expecting to see her bouncing from airport to airport … but nope, there goes her line. She went all the way up through the boreal to Alaska, then across to Russia and back across the Pacific to northern California. It all checked out, and since then she’s transmitted several times. She’s bouncing around the Sutter Buttes area, just doing what ducks do.”

This map shows the 10,000-mile trip the hen took from Louisiana to Russia and back to California. courtesy of Paul Link

Link was surprised, but he was even more shocked a few days later, when he saw that one of the hens fitted with an old-school transmitter had taken what he calls an “eerily similar route” to Russia.

“In fact, at three different points throughout their migration between Rockefeller and Russia they were within a couple hundred meters of each other,” Link says. “It’s hard to wrap my head around it, but they were on the same wetland at the same time in northeast South Dakota, and in Russia they were within a couple hundred meters of each other, but five weeks apart.

“Every time I see stuff like this it makes me wish I could get on a plane and go look at it,” he continues. “You know it’s something special when birds put their feet on the same piece of ground—or on the same sandbar in the same river.”

While the flight paths of the two hens were similar, their stories are somewhat different. By looking closely at the transmitter data, which shows exactly how long each of the birds stayed in one place, Link ascertained that the first pintail hen tried to nest in South Dakota in early April. She lost her nest after eight days—Link assumes it was depredated—and then she took off for Russia. But the second hen never even tried to nest before moving on.

“When this bird passed through the eastern Dakotas this spring, it was a desert,” Link says. “The ground was brown, and the few semi-permanent wetlands were sheet ice. So, she literally went another 4,000 miles and never initiated a nest. Just said this isn’t the year, I’m not going to risk my own health and waste the energy.”

Forced Migrations

Aside from giving waterfowl researchers something to scratch their heads over, the epic journeys these two ducks undertook could also serve as proof that pintails are being forced to migrate further north because of climate change and habitat loss. Last month, Outdoor Life reported on the prolonged drop in pintail populations in this year’s waterfowl survey, and one scientist theorized that we could be looking for pintails in the wrong places during surveys.

Both pintails passed through the Dakotas this spring on their way to Russia, but only one attempted to nest. Matthewadobe / Adobe Stock

“It could be they’re losing habitat, or it could be they’re actually gaining habitat in the north due to climate change,” explained Delta Waterfowl biologist Dr. Chris Nicolai. “And they’re just starting to move out of the areas we’re surveying, and we’re missing them.”

Link and other researchers have discussed the forced migration theory as well, and he says that in the case of the second pintail that flew to Russia, this is exactly what happened. After choosing not to nest in the PPR, the bird left the survey area prior to May 1 and was not included in this year’s duck count.

He also says it would make sense for the birds to fly farther north than they have historically because of the amount of habitat they’re losing on the prairie. And since pintails migrate earlier than other ducks, they can’t hang around and wait for conditions to improve in a drought year—which is what gadwalls, mallards, and a lot of other mid- to late-nesters do.

“Pintails have a lot going against them. When they show up on the landscape, it’s boom or bust. If the conditions aren’t perfect, a lot of them aren’t even going to attempt to nest,” Link explains. “They’re also attracted to the shortgrass prairie landscapes, and thats the area that’s seen the largest conversion to row crops here in recent years. They estimate that 1.8 million acres of native prairie was converted to annual agriculture in the Prairie Pothole Region alone last year.”

Unlocking the Secrets of Birds

Looking at all 57 of the pintails that were tagged in Louisiana this January, it’s clear that we still have a lot to learn about these birds. The two far-flying hens that Link tracked were obviously the most intriguing of the bunch, but it’s possible that they’re not so much exceptions to the rule as they are examples of what ducks are capable of.

At least eight or nine of the tagged birds didn’t survive nesting season. Their transmitters were recovered by Link and other researchers in the Dakotas and Canada. Meanwhile, two other pintails that Link is still tracking might have made it all the way to Russia this summer, but instead they did something that he finds even more fascinating. They turned around.

Paul Link pulls birds from the net at Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge; Link works with graduate students to capture ducks from the refuge in January. courtesy of Paul Link

Link explains that although conditions in the PPR were bleak in early April, things improved substantially at the end of the month when two good blizzards hit the region.

“We actually had a couple pintails that somehow knew that,” he says. “They were up along the edge of the parklands in the boreal forest in central Canada, and they actually turned around and went back to the eastern Dakotas and successfully nested.”

The way Link sees it, there’s only one explanation for why those ducks turned around. Why else would they go back to a place that they flew over weeks before and deemed unfit for nesting?

Read Next: Pintails Hit Their Lowest Population in Decades. Some Researchers Think We Could be Miscounting Them

“There’s no reason other than birds communicating with each other. Ducks obviously share information, and they have a communication network that we underestimate,” Link says. “I’m sure there’s been a bird sitting in the parklands when another bird drops into their wetland and is over there chattering: ‘You wouldn’t believe how much water there is in the Dakotas, it’s over the roads!’ Stuff like that absolutely happens and nobody will ever convince me otherwise.”

Waterfowl researchers may never fully understand what makes ducks tick, or why one pintail would stay in the Dakotas while another flies to Russia. But that won’t keep Link and others from trying.

“As we unlock all these little secrets,” he says, “they’re surprising us at every corner.”

The post How Far Can Ducks Migrate in a Day? About 2,000 Miles appeared first on Outdoor Life.

By: Dac Collins

Title: How Far Can Ducks Migrate in a Day? About 2,000 Miles

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/conservation/pintail-duck-migrate-russia-louisiana/

Published Date: Fri, 28 Oct 2022 15:09:48 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://manstuffnews.com/weekend-warriors/3-classic-striper-surf-lures-you-should-be-throwing-right-now

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions