Valentin Popov is the owner of Tower Lodge Outfitters in Saskatchewan. Andrew McKean

WHEN WE WERE INTRODUCED, Valentin Popov declined my handshake. He was preoccupied with reattaching the severed tip of a finger, which he had hacked off earlier in the day with a machete as he trimmed birch branches above a bear bait.

Over the next week, as I cleared trails with Popov, wrangled his 4-wheeler through the bogs of northern Saskatchewan, and hunted black bears in his company, he would occasionally unbandage the finger, urinate on it, and then rewrap it with black electrical tape. “Keeps it clean,” he grunted when he noticed my raised eyebrows at this unorthodox antiseptic.

Popov has owned Tower Lodge Outfitting on the south shore of Dore Lake for a dozen years, but he hardly seems like the presiding head of this bear, deer, and fish camp. He shuns the role of back-slapping host, preferring instead to scuttle among the gear sheds, scrounging tools, repairing ATVs, prepping bear baits, and chainsawing in half the frozen beaver carcasses that adorn every bait site like the mangled cherry on a particularly gory sundae.

In short, he seems like an especially motivated guide, not the owner of a well-regarded hunting outfit.

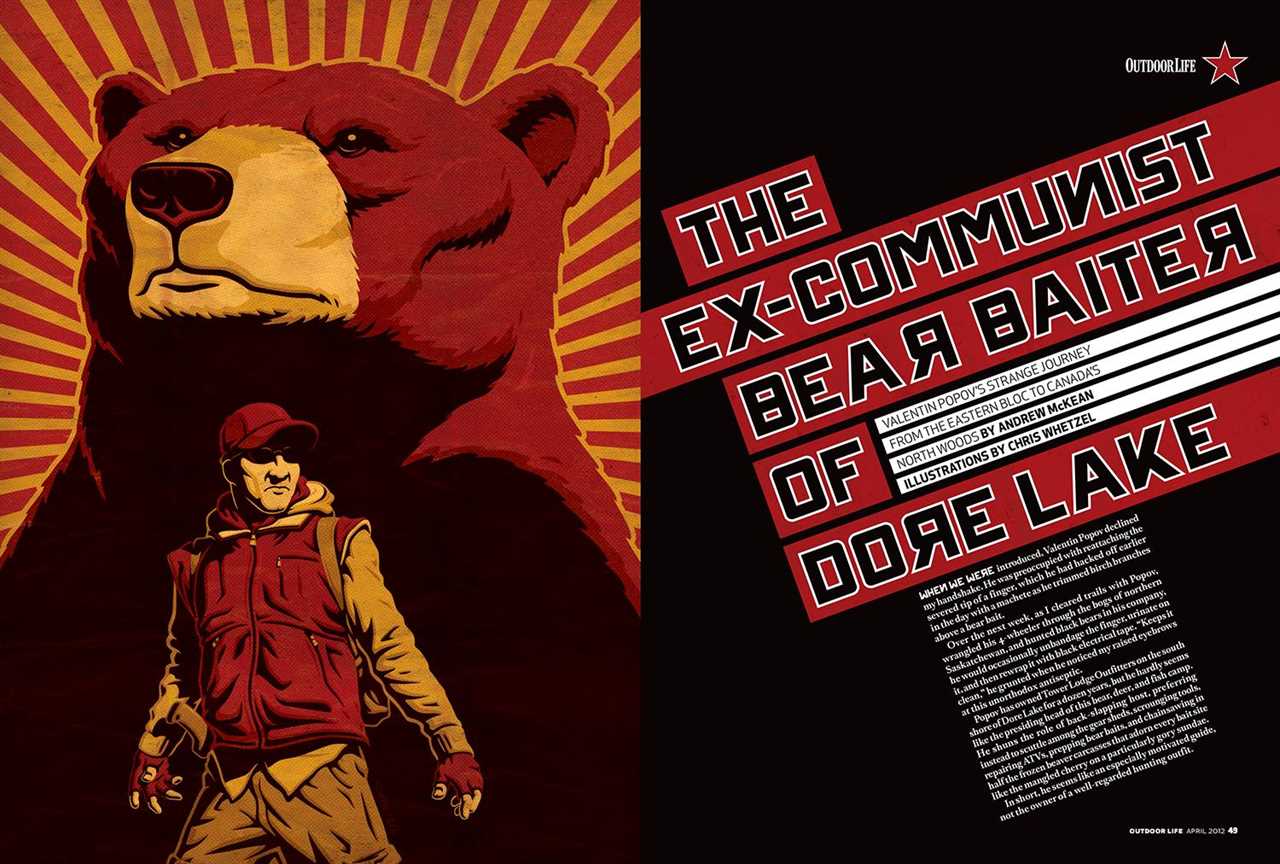

The original magazine spread, from April 2012, featured illustrations by Chris Whetzel. Outdoor Life

That’s as Popov wants it. Instead of shaking hands (we’ve established how hard that is for him) and holding court in the lodge, Popov is more comfortable delivering hunters to stands, skinning the bears they kill, then listening to their stories of curious sows and hungry boars that tried to climb their trees, wolves that howled all night, and northern lights that crackled along the horizon.

Popov says very little. Partly it’s his nature. Partly it’s his rough Slavic accent. He is a proletariatBulgarian by birth, but Popov is a north-woods homesteader by choice.

How he got here, to this timbered wilderness west of LaRonge, is equal parts Cold War intrigue, common criminality, and undiluted determination. But every day that he spends under the pale blue sky of the Canadian north, roaming the birch forests and blackberry briers, and tuning his senses to the seasonal movements of the bears that provide his income and his identity, confirms his decision 30 years ago to escape the soul-sucking Communists of his native Bulgaria.

Flight to Feedom

When he was 21 years old, Popov—then a conscript in the national army—got off an Air Bulgaria jet bound for Havana as it refueled in Newfoundland, walked up to an airport security guard, and said the only English word he knew, the word he had practiced for months back in Sophia: “Refugee.”

The Canadians gave him asylum, but Popov had nowhere to go and no one to receive him, and after a hungry month in Montreal, he committed the most ancient of crimes. He stole a loaf of bread. Caught, he was sentenced to a remedial work program. He learned how to fix automobiles, and when his sentence was over, he knew enough about cars and Canada to know he wanted to head west. He pulled out a map of the country, closed his eyes, and let his finger fall. It landed on Rosetown, Saskatchewan, a grainbelt town near the Alberta border. Popov got as far as Saskatoon, where he took a job in a body shop, working as an apprentice mechanic. Within five years, often working 20 hours a day, he owned the business. He wrote home asking his childhood friend Vi if she wouldn’t mind coming to Canada to be his wife.

Val Popov’s Tower Lake Lodge sits on the south shore of Saskatchewan’s Dore Lake. Andrew McKean

Val taught himself to speak English, but he reads it poorly and has difficulty writing it. So at his shop—which he says he owns in order to subsidize the outfitting business—he mainly “swings wrenches” with his employees, leaving Vi to answer phones, write checks, and deal with the administrative side of the business.

It’s the same way at camp. Vi picks hunters up at the airport, settles them into their cabins, and asks about food preferences and the weather back home. Val is in constant motion, as though something, or someone, is chasing him.

It turns out he is the one in pursuit.

Spend enough time with Val Popov and you realize that he is trying to capture what we are all after in one way or another: the clarity, freedom, and single-mindedness of youth.

This occurs to me in perhaps the most unwholesome quarter acre of forest I’ve ever seen. I’m helping Val prepare a bait site. Years of baiting bears have made this place look like an abandoned meth lab, or the unkempt camp of a backwoods hermit with an insatiable sweet tooth. The ground is littered with tattered plastic garbage bags, oats soaked in canola oil, stale doughnuts, post-date Gummi Bears, dog food, and the shattered Styrofoam trays that once held frozen smelt.

Val has a system for his bait sites, each of which features a 55-gallon oil drum with a dozen holes the size of a baby’s fist punched in the base. Into the drum he drops half a frozen beaver.

“The bears play with the beaver,” says Val. “They can’t get it, but they try to pull bits of it through the holes. It keeps them at the bait, and the longer they stay at a site, the more comfortable they feel about coming back.”

The barrel also serves as a reference for hunters.

“If the bear’s back is as high as the top of the barrel, shoot it,” Val says in a Slavic accent so thick that “it” sounds like “eet.”

A smaller plastic barrel is the centerpiece of the site. This is where Val stashes his bait, stuffed through a 6-inch hole in one end. He then sets the barrel on its side and pushes two or three deadfall spars into the opening. A bear is uniquely equipped to pull out the logs to get to the bait. A wolf might gnaw at the logs. A pine martin or fisher might try to stick a paw through the hole. But a bear will use its claws and substantial forearms to pull the timber out to get at the goodies inside the barrel. If Val arrives at the site and the spars are pulled out of the barrel, he knows a bear has hit the bait.

A strand of barbed wire tethers the plastic barrel to a tree. The wire is intended to keep the barrel from being carried off by an ambitious bear, but it also snags a hank of hair so Val can see in an instant the color of the bear hitting the site.

Popov prefers life in the bush to that of camp, clearing trails through the dense spruce and birch forests, and guiding hunters. Andrew McKean

Grandfather Nature

We are nearly finished freshening this particular site when Val looks up at the sky, watching a glossy-black raven swoop to the top of a towering spruce tree. The silence is just about to become awkward when Val finally speaks.

“This is why I love coming here. Do you hear it?”

I don’t hear anything, and am wondering if this is some sort of a backwoods initiation ceremony.

“Nothing,” Val says in his accent. “This place reminds me of Bulgaria, the places I walked with my grandfather. We walked every Sunday. In the mountains. In the forests. Around the lakes. It’s where I fell in love with the outside. The sounds of nothing.”

There’s no holding Val back now. We have been constant companions for four days. We are friends. He has something to say.

“This is what I could never understand about the Communists. They wanted to use nature. To make it work for them, the sawmills and factories. The dams. They didn’t want anybody to own anything. But they wanted to own nature. There were a lot of reasons why I had to leave, but that was the main one.”

Popov’s camp caters to anglers as well as hunters. Andrew McKean

And here’s where Val tells me his story, downwind of the thawing beaver. Of his heart-racing decision to leave the plane, of his despair at trading the cheerless apartments of Sophia for the gray sidewalks of Montreal, of the humiliation of stealing food, of his desire to own land of his own, to run a business where no one could tell him what to do. Of his affection for bears, which he describes in terms that parents reserve for children. Of his quest to find a place in the world where he can make his own decisions, and live with the results.

It occurs to me that I’m looking at the freest man I know, this displaced Communist turned modern-day homesteader. He knows what he wants and has the clarity of vision and strength of will to get it.

In his company I feel slightly inadequate and uninteresting.

Then Val spots a hank of brown-black hair hanging from his snag wire.

“That’s a bear worth waiting for,” he says, stacking empty bait buckets on the 4-wheeler. “Come. We have work to do.”

Before we can hunt, though, we must visit a half dozen bait sites, checking them for activity and filling the barrels when we find fresh sign.

Popov freshens his bear baits with a trademark mix of oats, canola oil, and dog food. Andrew McKean

At this early stage of the season bait is mainly recreational for bears this far north. After six months of hibernation, they are plugged up—“irregular” is the term we humans would apply to this gastric condition. They need roughage to spark their metabolisms, so they seek out greening grass in meadows and the sunny edges of deep timber. They come to the bait sites mainly to play, drawn by the exotic mix of scents and substances.

Val doesn’t get serious about hunting a site until he spots a plug, a greasy black wad of colon bile. Once a bear evacuates the plug, it will visit a bait site with consistency and enthusiasm.

Each site is named for its location or some memorable occurance that took place there. We visit Crazytown (named for the 13 bears that descended on the site at one time. “Crazy,” Val remembers, shaking his head). We bait Ben’s Cabin, Spooky, Stove (after a rusted relic from a trapper’s abandoned camp), Graveyard, Shockey’s (named for Jim, Val’s celebrity neighbor to the west), Three Lakes.

At Crazytown, we find a bear’s butt plug, and decide to hunt it the next day.

Crazytown

The dense timber and sucking mud of these boglands make driving a normal vehicle impossible. Instead, we drive Val’s side-by-side Rhino miles into the bush until we reach what looks like an abandoned relic of an industrial logging operation. It’s Val’s pride and joy, and it might be considered a mechanical version of himself—practical, muscular, and unpolished. Called a Nodwell, it’s a tracked swamp-bogger designed for the uranium mines and permafrost outposts to the north of here. Val cranks the tired diesel, and the Nodwell belches smoke and rattles like an oil drum half full of rusty nails. It looks like a tank that might have defended Stalingrad, but instead of a gun, it is armed with a dozer blade that flattens alders and willows as we blaze a trail to Crazytown.

Seeing his animated delight at working the twin track controls like some oil-field puppeteer, I start to question Val’s nearly holy regard for the quietude of nature. But after a couple of cacophonous miles, we shut off the Nodwell and walk to the bait, silent as squirrels in the greening woods.

I sit in the treestand for hours, feeling a little like an assassin staking out a convenience store. I watch a family of yearling cubs scamper around behind their mom, then a couple of juvenile bears playing tag. Just before dark, I see a big boar skulking in the trees behind the barrel. I’m ambivalent about shooting a bear I haven’t really hunted.

Then I recall my week in Val’s company, rigging bait barrels, soaking up his Old World wisdom, watching the north woods come alive in the rising spring. I have hunted hard and well, and this bear—a brown-black boar with a back as high as the barrel—is my reward.

This story originally ran in the April 2012 issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.

The post The Ex-Communist Bear Baiter of Dore Lake appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

By: Andrew McKean

Title: The Ex-Communist Bear Baiter of Dore Lake

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/ex-communist-bear-baiter/

Published Date: Thu, 11 May 2023 17:22:19 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://manstuffnews.com/weekend-warriors/takeaways-from-a-turkey-hunter-who-was-accidentally-shot-by-his-longtime-hunting-partner

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions