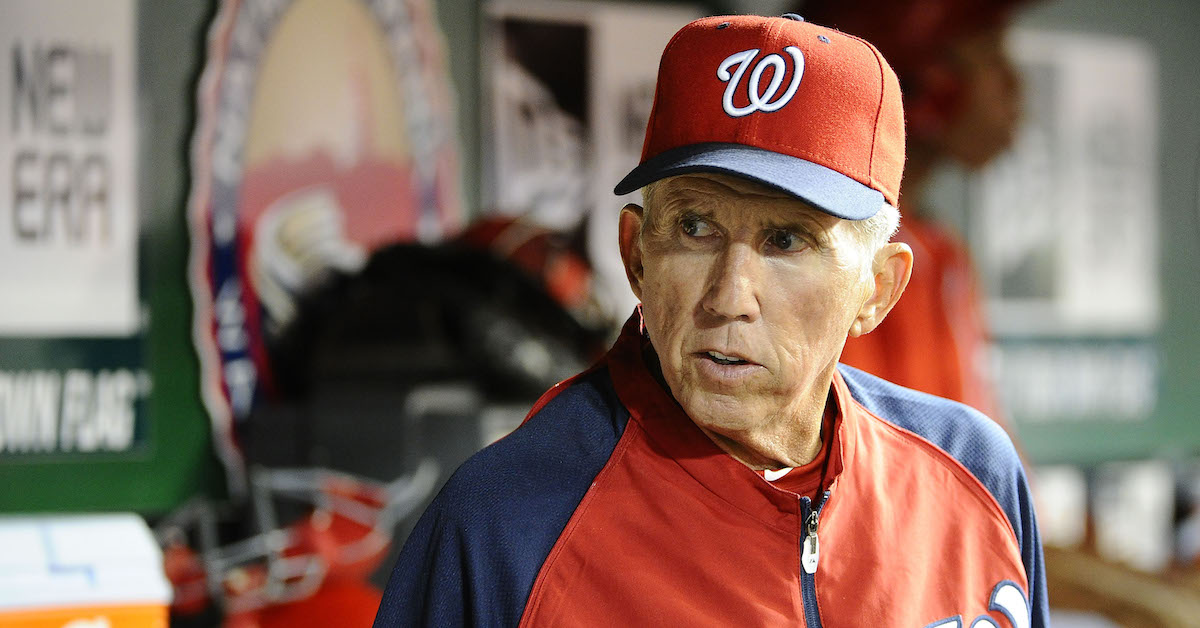

Brad Mills-USA TODAY Sports

This post is part of a series covering the 2024 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee Managers/Executives/Umpires ballot, covering candidates in those categories who made their greatest impact from 1980 to the present. For an introduction to the ballot, see here. The eight candidates will be voted upon at the Winter Meetings in Nashville on December 3, and anyone receiving at least 75% of the vote from the 16 committee members will be inducted in Cooperstown on July 21, 2024, along with any candidates elected by the BBWAA.

2024 Contemporary Baseball Candidate: Manager Davey Johnson

| Manager |

G |

W-L |

W-L% |

G>.500 |

Playoffs |

Pennants |

WS |

| Davey Johnson |

2443 |

1372-1071 |

.562 |

301 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

* Average based on the careers of 21 enshrined AL/NL managers from the 20th and 21st centuries

Davey Johnson

Like Billy Martin before him, albeit with far less drinking and drama, Davey Johnson was renowned for his ability to turn teams around. He posted a winning record in his first full season at four of his five managerial stops and took four of the five franchises that he managed to the playoffs at least once. But after six-plus seasons managing the Mets, he never lasted even three full seasons in any other job and never replicated the success he had in piloting the 1986 Mets to 108 wins and a World Series victory.

A fine player in his day, Johnson spent parts of 13 seasons in the majors (1965–75, 1977–78) with the Orioles, Braves, Phillies, and Cubs, hitting .261/.340/.404 (110 OPS+), making four All-Star teams and winning three Gold Gloves; he also spent two seasons in Japan. He’s perhaps best remembered for setting a single-season record for homers as a second baseman with Atlanta in 1973 (42, plus one as a pinch-hitter), and for being the first player with two pinch-hit grand slams in the same season in ’78. It was in Baltimore, where he was a key part of four pennant-winning teams (including the 1970 champions) under Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver, that the seeds of his managerial career were planted.

Johnson, who had graduated Trinity University with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, devoured Earnshaw Cook’s 1964 proto-sabermetric tome Percentage Baseball and came to appreciate its emphasis on on-base percentage. Upon persuading Orioles owner Jerry Hoffberger to let him use the IBM mainframe of the National Brewery (of which Hoffberger was chairman), he programmed the computer to test his theories about baseball. His printed-out presentation of his “Optimization of the Baltimore Orioles Lineup,” via which he argued he should bat second instead of sixth or seventh, wound up in Weaver’s trash can. “But I know he got it out of there after I left,” Weaver told ESPN’s Jerry Crasnick in 2011. Johnson absorbed plenty from the statistically inclined skipper, including his disdain for bunting in favor of swinging for the fences.

In 1979, as his career was winding down, Johnson got his first taste of managing via the Miami Amigos in the short-lived Inter-American League, which also had franchises in Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Puerto Rico. After that league folded at midseason, he managed the Mets’ Double-A affiliate in 1981 and then their Triple-A affiliate in ’83; at the latter stop, he introduced the use of a computer to minor-league baseball. He took that with him to the majors the following year, when general manager Frank Cashen hired him. The Mets had gone 68–94 under George Bamberger (who was fired on June 2) and interim manager Frank Howard in 1983. At his introductory press conference, Johnson gave reporters a taste of his unvarnished candor when he spoke of Howard agreeing to return to coaching on his staff by saying, “Frank is a stubborn man, he won’t hide his opinion from you. To be honest, I didn’t like the way he managed. But he’s a good baseball man.”

Johnson was decades ahead of his time in using statistical databases to figure out probabilities and optimize his lineup, though thanks to his experience as a player, he avoided much of the stigma that would later surface against the so-called Moneyball backlash. “Players aren’t machines,” he told the Boston Globe’s Lesley Visser in 1985, “but the chances of something happening in a particular situation are illustrated by the computer. I don’t run my club by computer, but I use it as another tool.”

Johnson’s players didn’t necessarily love knowing that their boss was using a computer, but fortunately, the Mets had talent, and Johnson got a lot out of the colorful, star-studded squad, which featured Gary Carter, Lenny Dykstra, Dwight Gooden, Keith Hernandez, Darryl Strawberry, and many more — at least until their hard-partying ways caught up. From 1984 to ’88, the team won at least 90 games every year, finishing no lower than second place.

Johnson’s arrival as a major league manager coincided with that of Gooden, the heat-throwing phenom. As a 19-year-old, he won NL Rookie of the Year honors, striking out 276 hitters and leading the Mets to 90 wins — 22 more than the previous season and the franchise’s highest total since its championship-winning 1969 squad. The next year, Gooden went 24–4 with a 1.53 ERA and 268 strikeouts en route to NL Cy Young honors. The Mets won 98 games, though they finished three behind the Cardinals in the NL East.

Though Gooden regressed in 1986, by this time the Mets had a top-notch rotation that also featured righties Ron Darling and Rick Aguilera and lefties Bob Ojeda and Sid Fernandez to go with a potent lineup. They claimed a share of first place on April 22 and never left; by July 1, they were 51–21, with a 10.5-game lead in the division. They not only won the NL East by 21.5 games but also tied for the NL’s highest win total since 1910, then beat the Astros in a tight six-game NLCS and the Red Sox in a thrilling seven-game World Series.

After winning 92 games but again finishing three behind the Cardinals in 1987, the Mets rebounded to win 100 games and the NL East in ’88. That team met an ignominious fate, however, losing a seven-game NLCS to the Orel Hershiser-led Dodgers after going 10–1 against them during the regular season. After New York slipped to 87 wins (and another second-place finish) in 1989, ongoing clashes with the front office made a 20–22 start in 1990 too much to survive. Johnson received news of his dismissal via a television report.

Still under contract with the Mets, Johnson didn’t get another managerial job until 1993. He interviewed to succeed Lou Piniella, who resigned after the 1992 season, in Cincinnati, and when 31-year-old general manager Jim Bowden hired Tony Perez instead, Johnson and fellow candidate Bobby Valentine both accepted jobs as consultants to the front office. When the Reds got off to a 20–24 start, Bowden chose to ditch Perez in favor of Johnson. The Reds finished just 73–89 but won the NL Central with Johnson at the helm in each of the two strike-shortened seasons, with records of 66–48 and 85–59; in the latter season, they swept the Dodgers in the Division Series but were swept by the Braves in the NLCS.

Despite that success, Johnson didn’t get along with owner Marge Schott, who was under suspension for “use of racially and ethnically insensitive language,” though she retained control of the team as general partner. Schott disapproved of Johnson living with his fiancée before marriage and wanted former Reds All-Star Ray Knight to manage the team instead. She hired Knight as assistant manager and announced in midseason that he would take over from Johnson for 1996 no matter how the team fared.

Johnson returned to Baltimore, where he took over a team that featured future Hall of Famers Cal Ripken Jr., Roberto Alomar, Eddie Murray, and Mike Mussina as well as Rafael Palmeiro and Brady Anderson, who hit 50 homers that season. The Orioles improved from 71 wins to 88 in 1996, claiming the AL Wild Card and then beating Cleveland in the Division Series before falling to the Yankees in the ALCS. The next year, with Harold Baines, Eric Davis, and Jimmy Key all joining the fold, the team won 98 games but again could get only so far as the ALCS. Another clash with an owner, this time Peter Angelos, led Johnson to fax in his resignation on the same day he was named the 1997 AL Manager of the Year.

Johnson next surfaced in Los Angeles, where he spent two undistinguished years at the helm of the Dodgers (1999 and 2000), a franchise in the midst of a jarring transition from the stability of the O’Malley family and long-tenured managers Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda to ownership by News Corp. and a revolving door in the manager’s office. Johnson feuded with general manager Kevin Malone, who was openly critical of him, and after the Dodgers topped out at 86 wins with the game’s third-highest payroll, he was fired.

Johnson spent over a decade away from the majors, dabbling in international baseball with the national teams of the Netherlands and the United States, guiding the latter in the 2009 World Baseball Classic. He finally returned to a major league dugout in mid-2011, at the age of 68, when he took over the Nationals after the unexpected resignation of manager Jim Riggleman. He had joined the team in 2006 as a consultant under Bowden, the team’s vice president and general manager; after Bowden resigned amid a federal investigation into a Latin American bonus-skimming scandal, Johnson became a senior consultant to GM Mike Rizzo in ’09. In his first full season back, he navigated a squad featuring 19-year-old Rookie of the Year Bryce Harper and pitching phenom Stephen Strasburg (who was controversially shut down in mid-September) to 98 wins. Though he would again win Manager of the Year honors, the Nationals squandered a two-run lead in the ninth inning of the fifth and deciding game of the Division Series against the Cardinals. While they won 86 games in 2013, they missed the postseason, and the 70-year-old Johnson was nudged back into a consulting role. He never managed again.

Hall-wise, Johnson’s career is a short one compared to those enshrined purely as managers. Among those from the 20th and 21st century, only Whitey Herzog and Billy Southworth managed fewer games, but both won at least three pennants, where Johnson only won one. His 1,372 wins rank a modest 33rd all-time, but on the other hand, his .562 winning percentage is 14th among those who managed at least 1,000 games — seventh if you limit the field to those who did so after the 19th century, behind the active Dave Roberts (.630) and Hall of Famers Joe McCarthy (.615), Southworth (.597), Frank Chance (.593), Al Lopez (.584), and Weaver (.583). Even including 19th-century managers, Johnson is 17th in games above .500, joining the 15th-ranked Dusty Baker and the 16th-ranked Roberts as the only ones among the top 21 who aren’t enshrined either as managers, pioneers/executives, or players.

That’s impressive stuff, but much less impressive is Johnson’s postseason track record. Four times — in 1986 and ’88 with the Mets, in ’97 with the Orioles, and 2012 with the Nationals — he took a team with the league’s best record into the postseason, yet only once did he make it through to the World Series. For as innovative as he may have been in the dugout, he would be the only post-19th-century manager enshrined without having won at least two pennants. In a format where voters are limited to selecting at most three candidates out of eight for their ballots and where two of the other three managers on the ballot (Jim Leyland and Cito Gaston) have multiple pennants, that works against Johnson.

Johnson has already struggled to stand out on a Hall of Fame ballot before. He was one of seven candidates stuck in the five-votes-or-fewer scrum on the 2019 Today’s Game ballot, which saw Baines and Lee Smith elected; Piniella (who’s also on this year’s ballot) fell one vote short. If I had a vote, I’m not sure one of my three spots would go to Johnson, though I wouldn’t rule him out without closer analysis of the other seven candidates.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/2024-contemporary-baseball-era-committee-candidate-davey-johnson/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions