Troy Taormina-USA TODAY Sports

Last week, I looked into the strange fact that starter usage hasn’t declined as precipitously as it first seemed over the past half decade. It’s downright strange that pitchers are throwing nearly as many pitches per start as they did in 2019, because it sure doesn’t feel that way. It’s even stranger that the average start length has declined by a mere half inning since 2008; I’m still scratching my head about that one even though I’m the one who collected the evidence.

One potential answer stood out to me: maybe I was just measuring the wrong thing. Meg Rowley formulated it a bit better when we discussed the article: Maybe by capturing all the pitchers in baseball, I was missing the change in workloads shouldered by top starters. In other words, no one remembers the pitcher who made the 200th-most starts (Xzavion Curry in 2023, Ryan Tucker in 2008), and the usage patterns of back-end starters don’t leave much of an impression in our minds. We care about the horses, the top guys who we see year after year.

Time for a new measurement, then. I took the same cutoff points from last week’s study, which serves to control for early-season workloads. But I further limited the data this time. I first took the 100 pitchers who had thrown the most innings in each year and called them “established starters” for the next year. Then I redid my look at pitch counts per start and innings pitched per start, but only for top pitchers in each year.

In theory, this handles the pitchers we’re interested in: rotation mainstays who are still good enough to get major league jobs. Through April 30, the cutoff point for my study, there had been 904 starts in the majors. “Established starters” made 407 of those, which feels like roughly the right cutoff. How has those guys’ workload changed? Eh, basically the same as everyone else’s:

Established Starter Usage Change, Pitches/Start

| Year |

Established Starter Pitches/Start |

All Pitchers Pitches/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

96.2 |

93.5 |

2.7 |

| 2009 |

97.6 |

95.2 |

2.4 |

| 2010 |

99.3 |

97.6 |

1.7 |

| 2011 |

98.6 |

96.8 |

1.8 |

| 2012 |

98.2 |

96.1 |

2.1 |

| 2013 |

97.4 |

95.1 |

2.3 |

| 2014 |

98.1 |

95.8 |

2.3 |

| 2015 |

95.1 |

92.5 |

2.6 |

| 2016 |

95.8 |

94.2 |

1.6 |

| 2017 |

93.3 |

91.7 |

1.6 |

| 2018 |

92.3 |

90.1 |

2.2 |

| 2019 |

91.3 |

87.6 |

3.7 |

| 2020 |

84.6 |

79.2 |

5.4 |

| 2021 |

87.3 |

83.1 |

4.2 |

| 2022 |

84.4 |

80.2 |

4.2 |

| 2023 |

89.6 |

86.9 |

2.7 |

| 2024 |

88.7 |

86.2 |

2.5 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

Established Starter Usage Change, IP/Start

| Year |

Established Starter IP/Start |

All Pitchers IP/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

5.99 |

5.75 |

0.24 |

| 2009 |

6.04 |

5.78 |

0.26 |

| 2010 |

6.10 |

5.91 |

0.19 |

| 2011 |

6.14 |

6.01 |

0.13 |

| 2012 |

6.30 |

6.01 |

0.29 |

| 2013 |

6.04 |

5.83 |

0.21 |

| 2014 |

6.06 |

5.9 |

0.16 |

| 2015 |

6.01 |

5.78 |

0.23 |

| 2016 |

5.85 |

5.73 |

0.12 |

| 2017 |

5.76 |

5.61 |

0.15 |

| 2018 |

5.66 |

5.46 |

0.20 |

| 2019 |

5.52 |

5.28 |

0.24 |

| 2020 |

5.14 |

4.73 |

0.41 |

| 2021 |

5.40 |

5.07 |

0.33 |

| 2022 |

5.20 |

4.91 |

0.29 |

| 2023 |

5.35 |

5.18 |

0.17 |

| 2024 |

5.48 |

5.24 |

0.24 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

There’s nothing to see here. The starters who threw the most innings in one year look a lot like the overall major league population in the next, at least in terms of pitches per start. They get through more innings because, well, they’re better. But the divide between that top group and the overall population is consistent from one year to the next. There’s no sudden decline in the workload shouldered by the very best; the path there mirrors the slight decline in pitches and innings that we’ve seen across the league.

That’s hardly proof that nothing’s going on. Maybe 100 is the wrong cutoff. Let’s do it again with the top 50:

Top Starter Usage Change, Pitches/Start

| Year |

Top Starter Pitches/Start |

All Pitchers Pitches/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

96.3 |

93.5 |

2.8 |

| 2009 |

98.5 |

95.2 |

3.3 |

| 2010 |

100.7 |

97.6 |

3.1 |

| 2011 |

101.3 |

96.8 |

4.5 |

| 2012 |

99.8 |

96.1 |

3.7 |

| 2013 |

99.7 |

95.1 |

4.6 |

| 2014 |

100.6 |

95.8 |

4.8 |

| 2015 |

95.8 |

92.5 |

3.3 |

| 2016 |

96.9 |

94.2 |

2.7 |

| 2017 |

94.8 |

91.7 |

3.1 |

| 2018 |

93.7 |

90.1 |

3.6 |

| 2019 |

92.6 |

87.6 |

5.0 |

| 2020 |

86.5 |

79.2 |

7.3 |

| 2021 |

88.5 |

83.1 |

5.4 |

| 2022 |

86.2 |

80.2 |

6.0 |

| 2023 |

90.3 |

86.9 |

3.4 |

| 2024 |

89.6 |

86.2 |

3.4 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

Top Starter Usage Change, IP/Start

| Year |

Top Starter IP/Start |

All Pitchers IP/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

6.02 |

5.75 |

0.27 |

| 2009 |

6.08 |

5.78 |

0.30 |

| 2010 |

6.18 |

5.91 |

0.27 |

| 2011 |

6.36 |

6.01 |

0.35 |

| 2012 |

6.43 |

6.01 |

0.42 |

| 2013 |

6.24 |

5.83 |

0.41 |

| 2014 |

6.25 |

5.9 |

0.35 |

| 2015 |

6.13 |

5.78 |

0.35 |

| 2016 |

6.00 |

5.73 |

0.27 |

| 2017 |

5.85 |

5.61 |

0.24 |

| 2018 |

5.88 |

5.46 |

0.42 |

| 2019 |

5.64 |

5.28 |

0.36 |

| 2020 |

5.29 |

4.73 |

0.56 |

| 2021 |

5.60 |

5.07 |

0.53 |

| 2022 |

5.38 |

4.91 |

0.47 |

| 2023 |

5.50 |

5.18 |

0.32 |

| 2024 |

5.57 |

5.24 |

0.33 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

Honestly, there’s still very little to see here. The top 50 starters in baseball, as measured by workload, are also pitching less than they did 15 years ago, but not by as much as you’d expect. I’ll admit that I’m surprised the top 50 starters in the game averaged just over six innings per start around 2010, but hey, the data is the data.

Just for completeness’ sake, I cut it off again at the top 25. Yet again, there isn’t much to see:

Elite Starter Usage Change, Pitches/Start

| Year |

Elite Starter Pitches/Start |

All Pitchers Pitches/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

99.9 |

93.5 |

6.4 |

| 2009 |

99.5 |

95.2 |

4.3 |

| 2010 |

101.2 |

97.6 |

3.6 |

| 2011 |

102.3 |

96.8 |

5.5 |

| 2012 |

101.7 |

96.1 |

5.6 |

| 2013 |

100.1 |

95.1 |

5.0 |

| 2014 |

103.9 |

95.8 |

8.1 |

| 2015 |

97.1 |

92.5 |

4.6 |

| 2016 |

99.5 |

94.2 |

5.3 |

| 2017 |

98.3 |

91.7 |

6.6 |

| 2018 |

94.6 |

90.1 |

4.5 |

| 2019 |

92.8 |

87.6 |

5.2 |

| 2020 |

88.7 |

79.2 |

9.5 |

| 2021 |

91.2 |

83.1 |

8.1 |

| 2022 |

88.0 |

80.2 |

7.8 |

| 2023 |

92.1 |

86.9 |

5.2 |

| 2024 |

90.8 |

86.2 |

4.6 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

Elite Starter Usage Change, IP/Start

| Year |

Elite Starter IP/Start |

All Pitchers IP/Start |

Gap |

| 2008 |

6.26 |

5.75 |

0.51 |

| 2009 |

6.26 |

5.78 |

0.48 |

| 2010 |

6.27 |

5.91 |

0.36 |

| 2011 |

6.45 |

6.01 |

0.44 |

| 2012 |

6.62 |

6.01 |

0.61 |

| 2013 |

6.30 |

5.83 |

0.47 |

| 2014 |

6.42 |

5.9 |

0.52 |

| 2015 |

6.34 |

5.78 |

0.56 |

| 2016 |

6.21 |

5.73 |

0.48 |

| 2017 |

6.08 |

5.61 |

0.47 |

| 2018 |

5.96 |

5.46 |

0.50 |

| 2019 |

5.70 |

5.28 |

0.42 |

| 2020 |

5.45 |

4.73 |

0.72 |

| 2021 |

5.74 |

5.07 |

0.67 |

| 2022 |

5.52 |

4.91 |

0.61 |

| 2023 |

5.66 |

5.18 |

0.48 |

| 2024 |

5.68 |

5.24 |

0.44 |

Note: All tables in this article use starts from roughly the first month of each season to capture early-season usage patterns

Yes, very good starters throw both more innings per start and more pitches per start than their less-qualified counterparts. No, that relative usage gap isn’t changing. For the last two years in aggregate, starters are down an average of 9.2 pitches and .67 innings per start from the numbers they averaged from 2008 to 2014. Among established starters, the top 100 group, they’re down 8.8 pitches and .68 innings per start. Cut it off at the top 50, and they’re down 9.6 pitches and .69 innings per start. Go even further to the top 25, and it’s 9.8 pitches and .7 innings per start. There’s a bit of a signal there, but it’s small. Half a pitch per start of difference between the league as a whole and its best arms isn’t quite the smoking gun I was hoping for to show that elite pitcher behavior is evolving differently than the rank and file.

On to the next potential explanation, then. I like to call this one “averages suck.” Imagine a world where six of every nine starters threw a complete game, and the other three didn’t even record an out before getting chased, the ultimate in-and-out openers. This world would look absolutely nothing like the way we experience pitching workloads, but it’d average six innings per start.

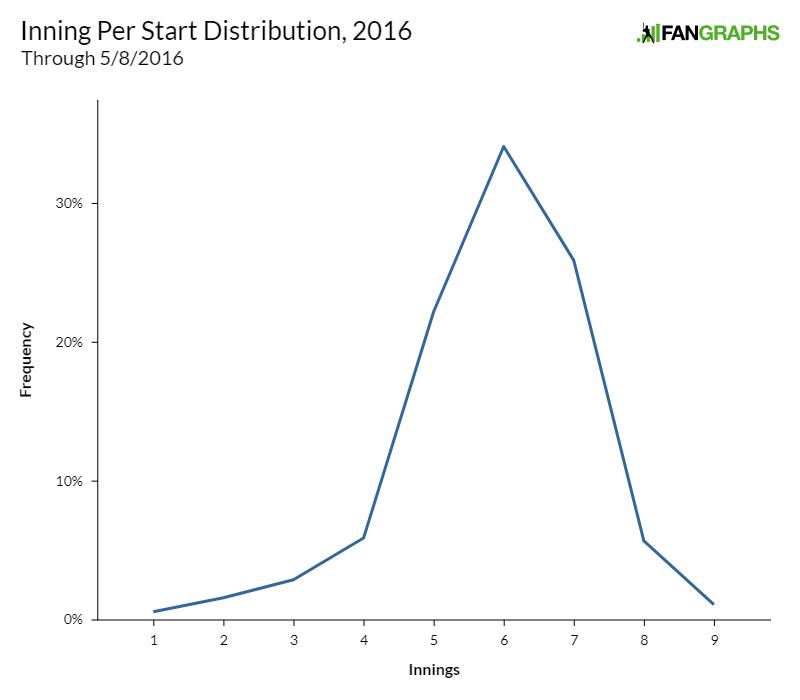

That’s not a reasonable world, obviously. In practice, innings pitched per start follow a fairly normal distribution. Here’s the distribution from the first month or so of 2016, to pick the midpoint of our sample:

A quick note on the scale: “1” means starts that lasted one inning or less; “2” means starts that lasted more than one inning, but no more than two innings – the starter recorded four, five, or six outs, in other words. That pattern continues all the way up. “9” is the only other bucket that needs explanation; that’s every start of 8.1 innings or more.

One theory of why starts feel so much shorter despite the average start length mostly not budging is that the edges are getting squeezed. Seven, eight, and nine inning starts have declined markedly. But what if two and three inning starts have declined markedly too? You can imagine why this might happen. Perhaps managers have gotten smarter about dealing with the limitations of modern usage. If you need your bullpen every night, you might be more hesitant to send your starter to the showers after only two innings. That’s seven innings your bullpen will have to pick up, and you’ll need them the next few games, because you need them every game. Surely, the starter can wear a few extra frames.

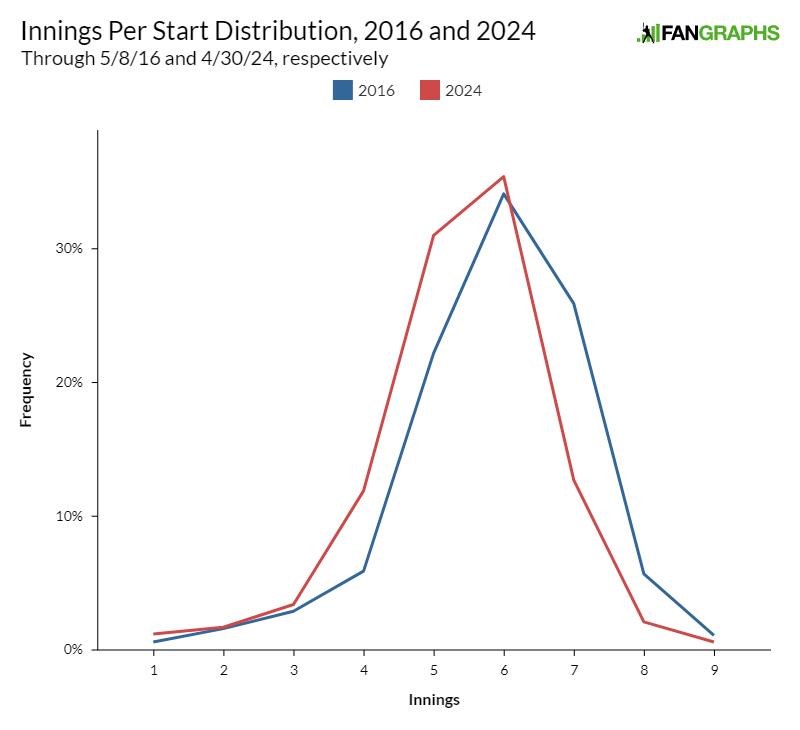

If that were the case, you’d expect the average to remain the same even as the distribution clumped up towards five-inning starts. The short starts of the past would get artificially lengthened as a bullpen preservation method. No one remembers the difference between a two-inning start and a three-inning start, but if that inning is offsetting another start that declines from seven to six, that could explain the dissonance here. Just one problem with that theory: it doesn’t hold up. Here’s 2024 by start length overlaid on 2016:

Aw, shucks. Seems like this theory doesn’t quite cut it either. We can bucket out the wings into starts of three or fewer innings, and starts of 6.1 or more innings. The story that tells isn’t one of compression; it’s one of everything heading down at the same time:

Inning Per Start Distribution, 2008-24

| Year |

<=3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

6.1+ |

| 2008 |

6.6% |

7.3% |

19.7% |

31.1% |

35.3% |

| 2009 |

4.8% |

7.2% |

22.0% |

32.6% |

33.4% |

| 2010 |

4.5% |

7.1% |

17.6% |

32.5% |

38.2% |

| 2011 |

4.2% |

4.9% |

15.4% |

34.8% |

40.7% |

| 2012 |

4.1% |

5.9% |

16.2% |

30.7% |

43.0% |

| 2013 |

4.0% |

7.2% |

19.4% |

33.7% |

35.7% |

| 2014 |

3.1% |

6.9% |

19.6% |

32.8% |

37.5% |

| 2015 |

5.2% |

6.1% |

20.5% |

33.1% |

35.2% |

| 2016 |

5.2% |

5.9% |

22.2% |

34.1% |

32.7% |

| 2017 |

5.1% |

8.1% |

22.6% |

37.3% |

26.9% |

| 2018 |

6.0% |

9.5% |

25.1% |

36.6% |

22.8% |

| 2019 |

8.3% |

11.3% |

27.0% |

33.4% |

20.0% |

| 2020 |

16.8% |

19.4% |

24.9% |

26.1% |

12.8% |

| 2021 |

11.0% |

14.3% |

28.7% |

29.9% |

16.0% |

| 2022 |

12.1% |

14.2% |

33.1% |

26.8% |

13.8% |

| 2023 |

7.3% |

12.0% |

31.6% |

34.9% |

14.1% |

| 2024 |

6.3% |

11.9% |

31.0% |

35.4% |

15.4% |

Very brief starts spiked at the start of the 2020, 2021, and 2022 seasons, which makes sense in all three cases. There was the mid-summer pandemic season start in 2020, then every pitcher was recovering from that weird year in 2021, and then the lockout delayed spring training in 2022. We’ve snapped back down to mid-single-digit rates of brief starts. We’re still seeing more than we did a decade ago, though, so it’s not an issue of fewer short starts flattering the data.

To the contrary, it seems that we’re largely seeing a parallel shift. More and more starters are making starts of 3.1-4 innings. The same is true of 4.1-5 inning starts. Starts between 5.1-6 innings have remained roughly constant; I can’t prove it, but my guess is that a lot of the starts that now go six innings would have gone longer in the past. Meanwhile, some starts that would have gone six innings in the past are now going five, and so on. The center of the distribution is moving down, in other words.

Another way of looking at it: I aggregated some buckets to try to capture the trend. In the first month of the 2008 season, 56.7% of starts went between 5.1 and seven innings, while 50.8% went between 4.1-6 innings. Only 27% went between 3.1-5 innings. Now, the bulk of the distribution is in that 4.1-6 inning grouping. I understand that these are overlapping, but I think that tells the story better. The probability distribution is evenly centered around 4.1-6 inning starts now. It used to be skewed longer:

Inning Per Start Distribution, 2008-24

| Year |

4-5 |

5-6 |

6-7 |

| 2008 |

27.0% |

50.8% |

56.7% |

| 2009 |

29.2% |

54.6% |

55.6% |

| 2010 |

24.7% |

50.1% |

58.2% |

| 2011 |

20.2% |

50.2% |

64.0% |

| 2012 |

22.2% |

46.9% |

61.2% |

| 2013 |

26.6% |

53.1% |

59.4% |

| 2014 |

26.6% |

52.4% |

60.5% |

| 2015 |

26.5% |

53.5% |

59.3% |

| 2016 |

28.1% |

56.2% |

60.0% |

| 2017 |

30.7% |

59.9% |

58.2% |

| 2018 |

34.6% |

61.7% |

54.2% |

| 2019 |

38.3% |

60.4% |

50.7% |

| 2020 |

44.3% |

51.1% |

36.8% |

| 2021 |

43.0% |

58.6% |

42.4% |

| 2022 |

47.3% |

59.9% |

38.4% |

| 2023 |

43.6% |

66.5% |

47.0% |

| 2024 |

42.9% |

66.4% |

48.1% |

In other words, pretty much everything has been affected equally. This isn’t a case of the top starters losing a ton of workload while the average Joes of the world pitch the same as always. It isn’t the very short starts getting erased from the game and messing with our data. Everyone is just pitching a little less than they used to, and in a fairly uniform shift towards fewer innings.

Here, if you’re interested in messing with the data, are the inning-by-inning buckets from 2008 onwards:

Inning Per Start Distribution, 2008-24

| Year |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 2008 |

0.8% |

1.4% |

4.4% |

7.3% |

19.7% |

31.1% |

25.6% |

7.9% |

1.9% |

| 2009 |

0.6% |

1.2% |

3.1% |

7.2% |

22.0% |

32.6% |

23.0% |

7.9% |

2.4% |

| 2010 |

0.8% |

1.0% |

2.7% |

7.1% |

17.6% |

32.5% |

25.7% |

10.1% |

2.4% |

| 2011 |

0.3% |

1.0% |

2.9% |

4.9% |

15.4% |

34.8% |

29.2% |

8.3% |

3.2% |

| 2012 |

0.3% |

0.9% |

2.9% |

5.9% |

16.2% |

30.7% |

30.5% |

9.4% |

3.1% |

| 2013 |

0.9% |

1.3% |

1.9% |

7.2% |

19.4% |

33.7% |

25.7% |

8.0% |

2.1% |

| 2014 |

0.1% |

0.9% |

2.2% |

6.9% |

19.6% |

32.8% |

27.8% |

7.5% |

2.3% |

| 2015 |

0.4% |

0.9% |

3.9% |

6.1% |

20.5% |

33.1% |

26.2% |

8.0% |

1.0% |

| 2016 |

0.6% |

1.6% |

2.9% |

5.9% |

22.2% |

34.1% |

25.9% |

5.7% |

1.1% |

| 2017 |

0.9% |

1.5% |

2.7% |

8.1% |

22.6% |

37.3% |

20.9% |

4.8% |

1.2% |

| 2018 |

0.8% |

2.0% |

3.3% |

9.5% |

25.1% |

36.6% |

17.6% |

4.0% |

1.2% |

| 2019 |

1.8% |

2.1% |

4.4% |

11.3% |

27.0% |

33.4% |

17.3% |

2.3% |

0.4% |

| 2020 |

2.7% |

5.4% |

8.7% |

19.4% |

24.9% |

26.1% |

10.6% |

1.5% |

0.6% |

| 2021 |

2.2% |

3.4% |

5.4% |

14.3% |

28.7% |

29.9% |

12.5% |

2.3% |

1.2% |

| 2022 |

2.4% |

3.8% |

5.9% |

14.2% |

33.1% |

26.8% |

11.5% |

1.7% |

0.5% |

| 2023 |

0.8% |

1.7% |

4.9% |

12.0% |

31.6% |

34.9% |

12.1% |

1.5% |

0.5% |

| 2024 |

1.2% |

1.7% |

3.4% |

11.9% |

31.0% |

35.4% |

12.7% |

2.1% |

0.6% |

Also, just for funsies, I did the same analysis but limited it to only the top 100 pitchers, as defined above. Here’s that table:

Inning Per Start Distribution, 2008-24

| Year |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 2008 |

0.8% |

0.6% |

3.4% |

5.5% |

16.6% |

30.0% |

31.1% |

9.5% |

2.5% |

| 2009 |

0.6% |

0.4% |

2.4% |

5.9% |

18.4% |

30.8% |

27.5% |

10.9% |

3.0% |

| 2010 |

0.6% |

1.0% |

2.1% |

5.5% |

16.7% |

30.4% |

27.6% |

12.5% |

3.6% |

| 2011 |

0.4% |

1.0% |

2.2% |

4.8% |

14.8% |

30.9% |

31.7% |

9.8% |

4.4% |

| 2012 |

0.4% |

0.4% |

1.8% |

4.6% |

11.7% |

28.8% |

34.7% |

13.9% |

3.8% |

| 2013 |

0.6% |

1.3% |

1.5% |

4.4% |

17.6% |

33.0% |

28.8% |

10.2% |

2.7% |

| 2014 |

0.0% |

0.6% |

1.2% |

4.6% |

18.3% |

33.4% |

30.8% |

8.9% |

2.2% |

| 2015 |

0.2% |

0.4% |

3.7% |

2.6% |

18.3% |

33.1% |

30.1% |

10.0% |

1.6% |

| 2016 |

0.8% |

1.7% |

2.7% |

4.3% |

20.5% |

33.1% |

28.5% |

6.8% |

1.7% |

| 2017 |

0.8% |

1.4% |

2.4% |

6.1% |

20.8% |

37.1% |

22.9% |

6.5% |

1.8% |

| 2018 |

0.4% |

1.0% |

2.5% |

9.4% |

22.9% |

36.4% |

20.4% |

5.1% |

2.0% |

| 2019 |

0.9% |

0.9% |

3.7% |

10.1% |

24.8% |

32.7% |

23.3% |

2.6% |

0.9% |

| 2020 |

1.9% |

2.6% |

5.9% |

14.3% |

24.9% |

32.1% |

15.0% |

2.4% |

1.0% |

| 2021 |

1.7% |

2.6% |

3.0% |

11.1% |

24.1% |

34.7% |

17.6% |

3.5% |

1.7% |

| 2022 |

1.7% |

2.8% |

3.2% |

11.5% |

30.8% |

31.0% |

16.8% |

1.7% |

0.6% |

| 2023 |

0.6% |

1.1% |

3.4% |

11.5% |

29.1% |

36.4% |

14.9% |

2.3% |

0.6% |

| 2024 |

0.2% |

1.2% |

1.7% |

9.8% |

27.0% |

39.8% |

16.7% |

3.2% |

0.2% |

This looks basically the way you’d expect it to. Starters who managed a ton of volume in the previous year are still averaging more volume than the overall population. But while a whopping 44% of starts by top starters went 6.1 or more innings from 2008 through 2015, we’re down to around 20% now. The 5.1-6 inning bucket has grown to offset that. No matter how you look at the data, the conclusion seems clear: Every pitching workload has declined, just a little bit, across the board. It looks more dramatic to me when I look at the prevalence of very long starts, so maybe that’s a better way to tell the story, but the fact remains: workloads haven’t shortened that much, and the past half-decade looks like a plateau, but they’re down, and there’s no obvious reason for them to go back up.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/a-deeper-dive-into-pitcher-usage-trends/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions