Ken Blaze-USA TODAY Sports

In 2023, Emmanuel Clase ran a 3.22 ERA and a 2.91 FIP. His 44 saves were a career high and five more than any other pitcher. Compared to the rest of the league, he was great. Compared to prior versions of Emmanuel Clase, however, he was dreadful. In 2021 and 2022, Clase was an unstoppable force of nature, running a 1.33 ERA and a top-five groundball rate while striking out more than a batter per inning. Then in 2023, Clase fell off a cliff, though admittedly, he landed on another, still pretty lofty cliff; not with a splat, but gently, into some soft, leafy bushes.

What happened to Clase? Everything happened! There were situational factors and mechanical factors. There were changes in consistency and approach. Everything is connected when it comes to pitching, with one factor cascading upon another. The fun is in following the chain.

Let’s start with the obvious: Clase was due for some regression. He outpitched his peripherals in 2022, and then he underperformed them in 2023. Such is life:

Clase’s Luck Ran Out

| Year |

xwOBA-wOBA |

BABIP |

LOB% |

FIP-ERA |

| 2022 |

.032 |

0.222 |

72.3 |

0.62 |

| 2023 |

-.007 |

0.295 |

60.5 |

-0.31 |

His BABIP got much worse, especially with runners on base. Cleveland’s defense fell from fifth in baseball in 2022 to 13th in 2023, so it seems safe to chalk a large chunk of Clase’s BABIP woes up to some combination of defense and luck.

Clase also faced tougher batters in 2023, presumably because the balanced schedule meant he spent less time beating up on the rest of AL Central. In 2022, 44.7% of his pitches came against the Central, but in 2023, it was just 27.1% Big fish, bigger pond. In 2022, his opponents had a collective wOBA of .304 and xwOBA of .307. In 2023, those numbers were .311 and .313.

That’s it for the situational factors. They get us some of the way there, but the underlying metrics tell their own, very convincing tale:

Clase’s Stuff Ran Out

| Year |

Chase% |

Whiff% |

K% |

BB% |

Best Speed |

GB% |

Barrel% |

| 2022 |

46.2 |

30.1 |

28.4 |

3.7 |

75 |

64.5 |

2.2 |

| 2023 |

30.8 |

27.4 |

21.2 |

5.3 |

77.8 |

56.6 |

5 |

Clase earned fewer chases and fewer whiffs, resulting in more walks and fewer strikeouts. When batters did put the ball in play, they hit it harder and elevated it more. In other words, everything that can get worse got worse. Let’s update our original question: What happened to make Clase so much more hittable?

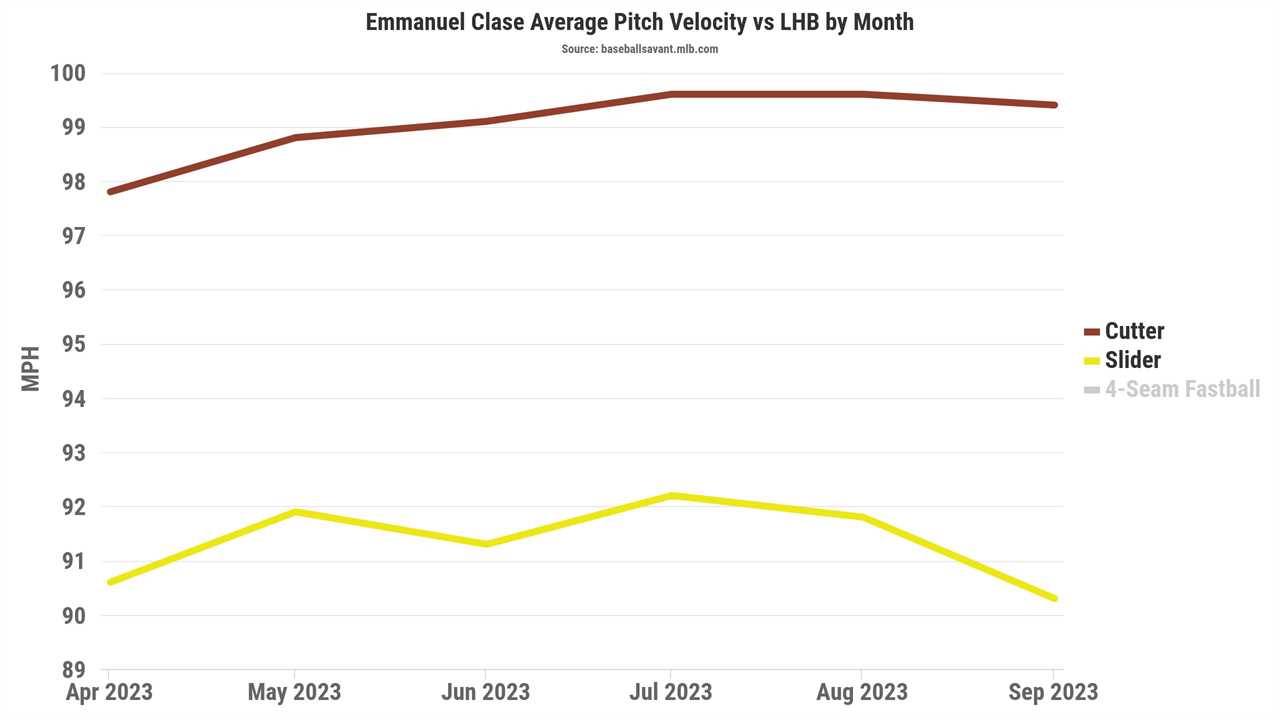

First, Clase lost a little bit of velocity. From 2022 to 2023, his cutter fell from averaging 99.5 mph to 99.1, and his slider fell from 91.9 to 91.1. However, it’s worth noting that much of that velocity loss occurred at the beginning of the season, and it ticked up later in the year:

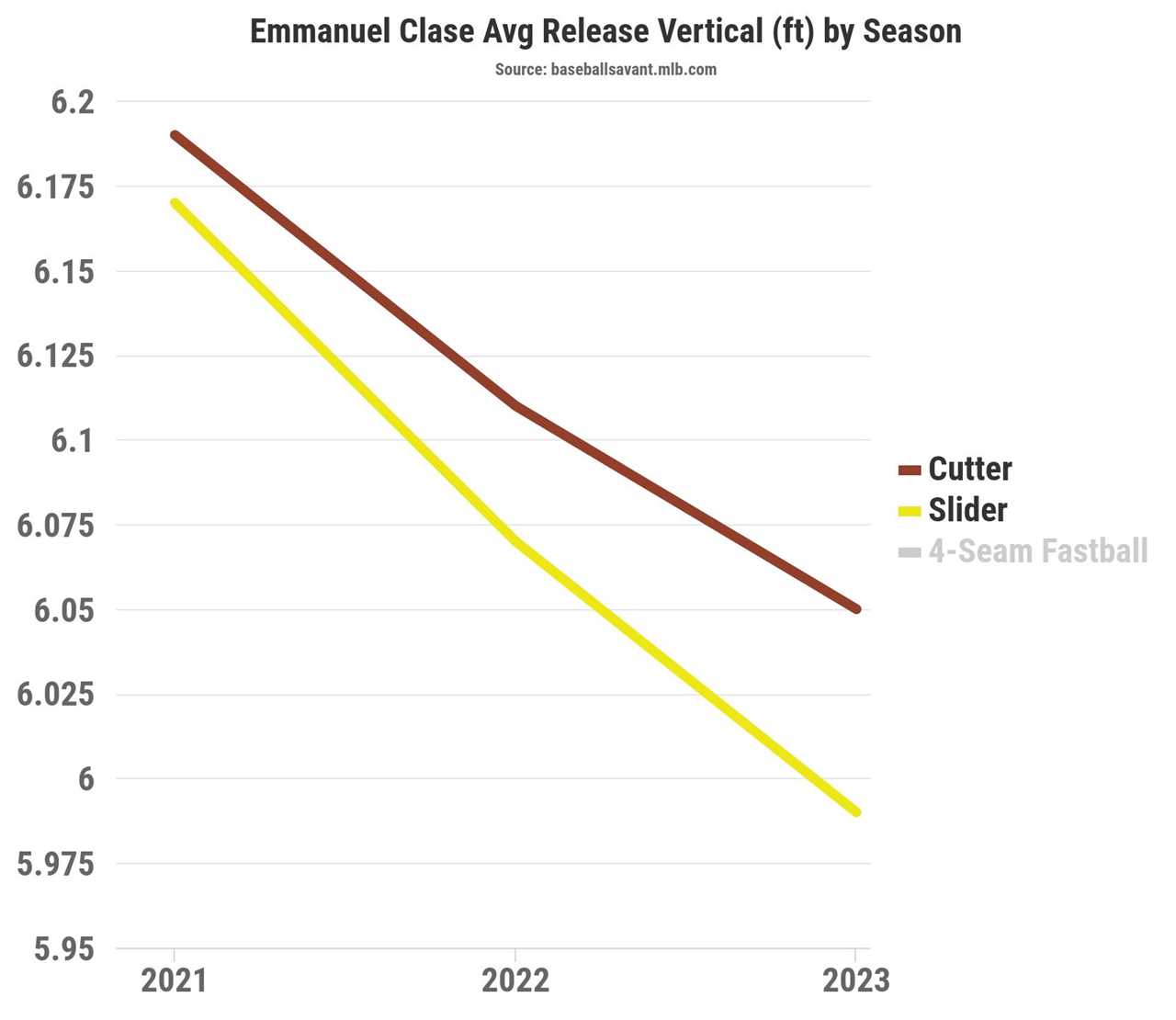

There wasn’t a big difference between Clase’s performance in the first half of the season and the second half, so we shouldn’t place too much blame on his velocity. Back in May, John Foley noted that one of the factors to which Clase and the Guardians attributed the drop was a lower release point. In fact, his release point has been dropping for the last two years, and the gap between his cutter and slider has been widening:

We’re only talking about roughly two inches over the last three years, but that doesn’t mean it’s nothing. I used the six-foot mark as a dividing line and pulled the splits on Clase’s slider in 2022:

Slider Splits by Vertical Release Point (2022)

| RP |

Pitches |

EV |

LA |

Brl% |

Whiff% |

Chase% |

| Above 6’0” |

258 |

86.6 |

5.4 |

0 |

44.6 |

57.4 |

| Below 6’0” |

101 |

85.7 |

6 |

4.8 |

35.6 |

42.6 |

The pitch performed much, much better when Clase released it higher. It racked up more chases and whiffs, and induced weaker contact. It makes a lot of sense that when the Guardians looked at Clase’s lower release point at the beginning of the 2023 season, they saw a problem. However, the problem never got rectified. Clase’s release point didn’t bounce back the way his velocity did. Maybe Clase tried and failed to adjust his release point. Maybe he didn’t try at all. Either way, he stopped running those huge splits in 2023:

Slider Splits by Vertical Release Point (2023)

| RP |

Pitches |

EV |

LA |

Brl% |

Whiff% |

Chase% |

| Above 6’0” |

171 |

89.2 |

7.6 |

3.2 |

28.1 |

34.7 |

| Below 6’0” |

204 |

89.2 |

13.8 |

6.7 |

33 |

30.8 |

That’s a whole lot messier. The splits are much smaller, and not necessarily in the same direction. It’s always difficult to pin a change in results on a mechanical change after the fact, but it’s even more dangerous to do so when the results are so murky.

Clase’s lower release point came along with changes to his movement profile, and in this case, they’re the exact changes you’d expect from someone with a lower, wider release point. His slider lost an inch of drop and his cutter lost an inch of rise, and both pitches also added an inch of sweep. Basically, Clase traded vertical movement for horizontal movement. That’s not necessarily an even trade, since vertical break is more helpful in getting whiffs. Perhaps even more important, those two lost inches of vertical break make the movement profiles of the cutter and slider a little less distinct:

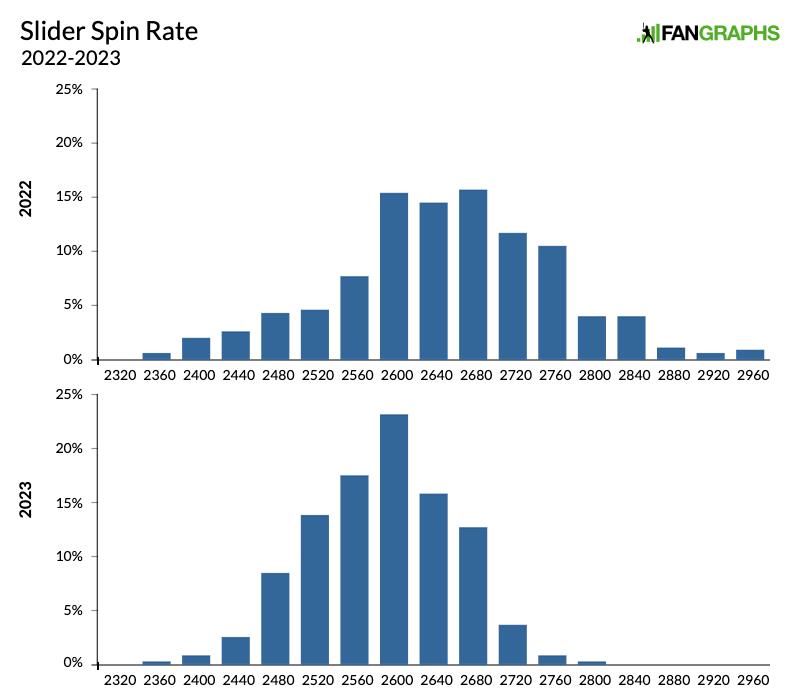

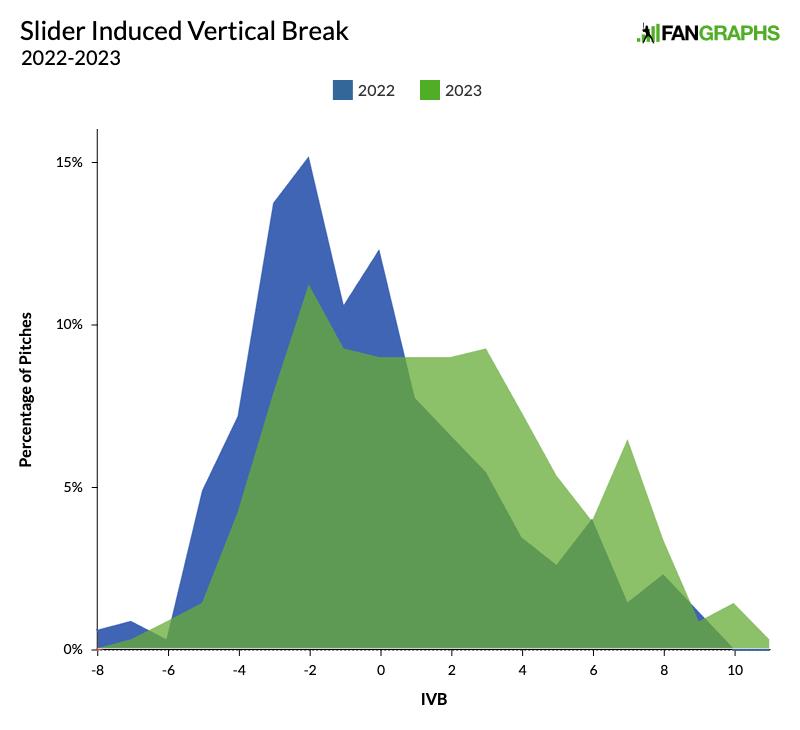

Clase’s slider also became much less consistent. I pulled the Statcast data for every tracked slider over the past two years and bucketed them into groups two ways. First, I looked at spin rate:

In 2022, Clase’s slider sat between 2,600 and 2,800 rpm, occasionally pushing 3,000. In 2023, he was almost never able to get up to 2,800 at all. That’s a pretty big change. Next, I bucketed the sliders by vertical break, independent of gravity. You’ll see two things going on, one on the left side of the graph and one on the right:

As with the spin rate graphs, Clase’s ceiling got lower. On the left, you can see that Clase couldn’t generate as much drop as he did in 2022. That’s not great, but it’s probably not as big a deal as what’s happening on the right side. Clase threw a whole lot more sliders that didn’t drop at all — or as you might know them, hanging sliders.

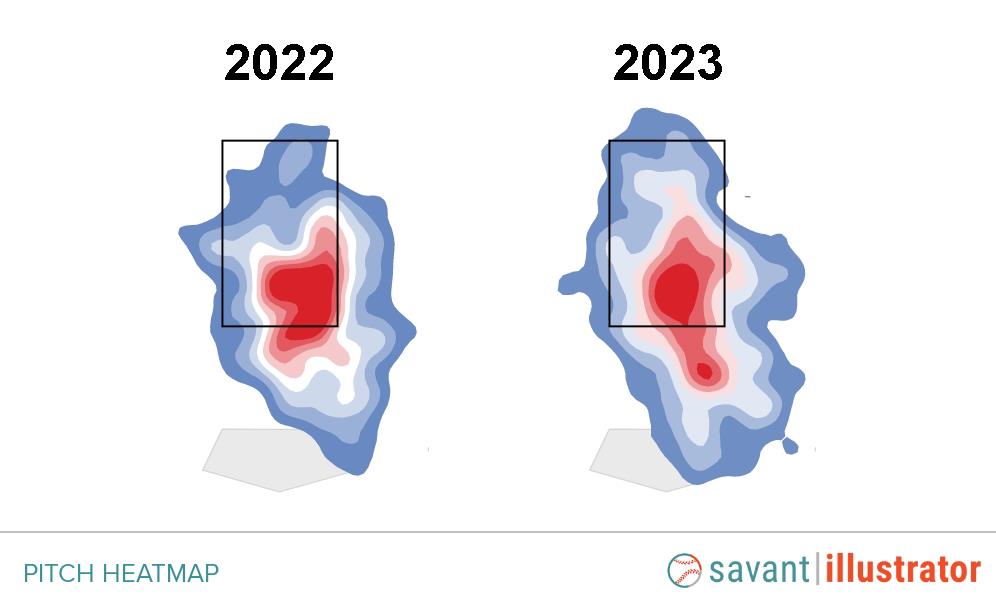

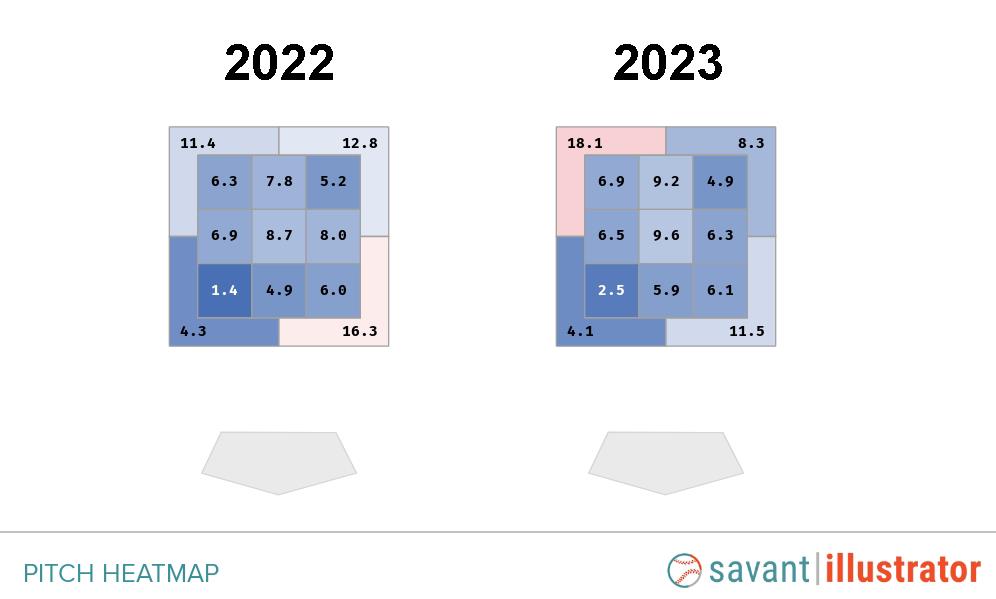

Now, movement isn’t the only factor here. A slider intentionally located up in the zone would also likely have less vertical break, but it seems safe to assume that most of this wasn’t intentional, especially when we look at where Clase has historically located his slider. Again, there’s no way to know whether this is related to his release point (or whatever caused the change in his release point in the first place), but Clase struggled with his control much more than he had in 2022:

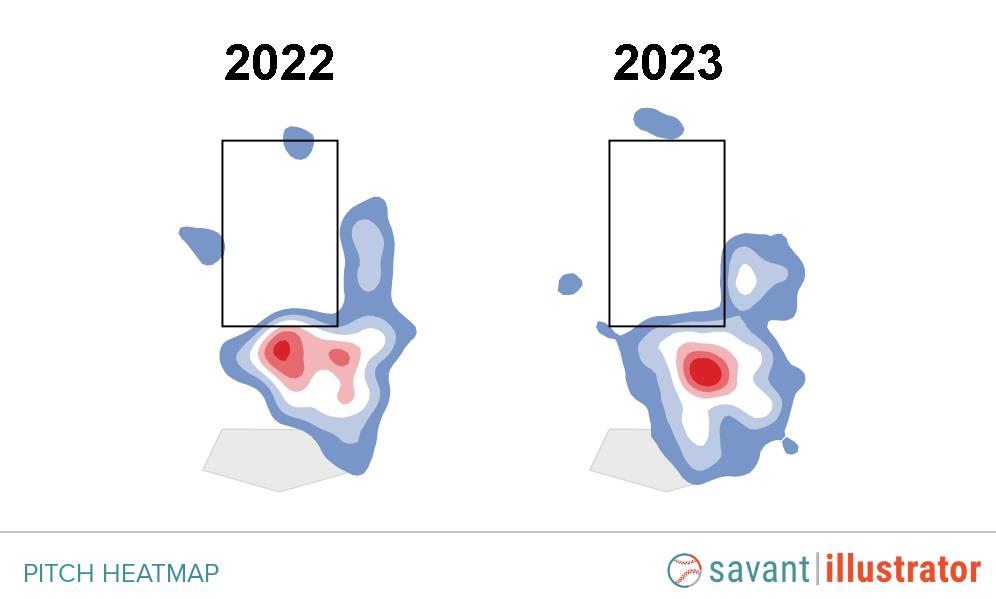

In 2022, Clase absolutely owned the outside corner. He was much less precise in 2023. Not only did the pitch leak back up and toward the middle of the plate, Clase wasn’t as good at locating it just beneath the zone, where it could earn the most chases. It’s easier to see if you focus on pitches outside the zone:

Look how much bigger the blob on the right is. Look how much farther the red parts are from the strike zone. That’s one way to earn fewer chases: make your pitches less tempting.

Here’s a turning point. So far I’ve been showing you the ways that Clase’s slider got worse from 2022 to 2023. As a result, I believe that Clase trusted his slider less than he did in 2023. This is where Clase being a two-pitch pitcher makes things really fun. It’s very easy to see which pitch he believes in at any given time. Clase threw his cutter 60% of the time in 2022, but he increased that to 67.6% in 2023. Look at how his pitch usage varied depending on the count:

Oddly, Clase threw the slider more when he was way behind, in 3-0 and 3-1 counts. It’s not as if Clase was pitching backward, throwing his slider more early in the count. In nearly every other count, the 2023 version of this chart has a lot more maroon than the 2022 version. That increased cutter usage is especially notable with two strikes. When he had two strikes, Clase threw the slider 40.9% of the time, compared to 54.4% in 2022:

Cutter Percentage by Count

| Year |

Even |

Behind |

Ahead |

| 2022 |

64.3 |

75.4 |

47.6 |

| 2023 |

68.9 |

78.2 |

56.9 |

| Difference |

+4.6 |

+2.8 |

+9.3 |

That in itself is part of the reason the slider’s chase rate was so much lower in 2023. He threw it a whole lot more in hitters’ counts, when they were much less apt to chase! When batters are behind, they’re more likely to protect on anything that looks like it could be close. In 2023, hitters chased 33.2% of the time when they were behind in the count, compared to 26.2% of the time when they were ahead or even. When pitchers are ahead, they’re more likely to bury a slider in the dirt looking for a chase, rather than trying to throw a perfect pitch that just catches the strike zone.

In two-strike counts, Clase’s slider had a 50.7% chase rate in 2022 and a 39.7% chase rate in 2023. That’s a drop-off of 11 percentage points, but it’s much less than the pitch’s overall drop-off of 20.5 points. That overall difference would have been smaller had Clase trusted the pitch more, especially in two-strike counts.

The surface numbers say that Clase’s slider was better than his cutter in 2023. By Baseball Savant’s run values, it was worth 1.2 runs per 100 pitches, compared to 0.3 for the cutter. It had a .211 wOBA, compared to .307 for the cutter. When batters did chase Clase’s slider, they whiffed more often than they had in 2022 (67.2% of the time, up from 60% in 2022).

However, take a look at what happens when we isolate even counts. In those counts, Clase’s slider had an RV/100 of 4.9 in 2022. That’s absurdly high. But in 2023, it dropped all the way to -0.3. It turned into a net negative! The cutter dropped as well, but from 1.4 to 0.6. It’s easy to understand why Clase trusted it more. Still, the cutter had its own control issues:

Instead of shooting for the outside corner, Clase often missed up and in to righties. I watched a couple dozen of those misses. Sometimes Clase was looking for a swing-and-miss with high heat, but a lot of the time he was just plain missing, unable to get on top of the ball at all.

You can understand why he might view that kind of miss as preferable to a miss with his slider. At least a 100 mph cutter above the zone changes the hitter’s eye line, making the next low pitch harder to hit. A slider that misses low and away doesn’t help as much to set up the next pitch, and a slider that misses over the heart of the plate is very bad indeed.

In the end, it’s not just that everything happened to Emmanuel Clase in 2023, it’s that everything is connected. There’s no way for us to know which of the factors I’ve mentioned affected which, but the line that I’ve been drawing goes something like this: Some underlying physical factor affected Clase’s release point, which affected his movement and his command, which affected his confidence in his slider, which made him throw his cutter more often. Independently, Clase’s batted ball luck tanked, which also could have fed into a distrust of his stuff. Through all of it, he was essentially the same pitcher, throwing two pitches in the hopes of inducing weak grounders and glove-side chases.

There is a lot more that could be written about Clase’s 2023. Despite pitching worse, having worse luck, and throwing his out pitch less often, he still managed to have a very productive year. He notched his second consecutive 40-save season, while also becoming the first pitcher in 17 years to rack up 12 blown saves. If I had to guess, I’d make the most boring prediction possible: the 2024 version of Emmanuel Clase will be somewhere in the middle. Still, I’ll be very curious to see how he gets there.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-concatenated-case-of-emmanuel-clase/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions