Courtesy of Andrew Golden

Your local beat reporter has the power to shape the way you see your favorite team. Day in and day out, it’s their voice delivering the good news and the bad, telling you what’s happening on the field and in the locker room. If you’re lucky enough to love a team with a good beat writer, it can absolutely deepen your relationship with the sport. A reporter might become required reading because they write beautifully, make you laugh, really know the game, ask good questions, or build great relationships with the players. If you don’t have a good beat writer, it’s easier to drift away from the team, and even the sport. They matter quite a bit, is what I’m saying. Despite that fact, beat reporters are rarely the focus. For all they mean to us, we don’t even see their faces all that often. Most of the time, all we see of a beat reporter is a disembodied hand holding a recording device (or, as in the picture below, the very tip of their nose).

It’s a complicated job. It requires knowledge of the game, constant creativity, tight deadlines, long hours, travel, and the ability to forge good relationships with players despite the fact that you sometimes have to stick a recorder in their face and ask, “So what was going through your mind when you made the error that cost your team the game?” In order to learn more about what the job actually entails, I reached out to Andrew Golden, who took over as the Washington Post’s lead beat writer covering the Nationals this season and has been on the beat for a few years.

Although he’s barely three years out of college, Golden’s credentials are imposing. In high school, he played baseball and wrote about sports for the school paper and for a blog he ran with some friends. He double-majored in journalism and African American studies at Northwestern, where he covered sports for the student newspaper, the Daily Northwestern, earning internships at the Kansas City Star, Chicago Tribune, and Washington Post. The Post internship came immediately after graduation, and he was hired full-time when it ended. Golden had spent three months covering the Washington Commanders and another three covering various sports when an editor asked him if he’d like to cover the Nationals, working with the lead beat writer at the time, Jesse Dougherty.

“I always loved baseball,” he told me. “It’s my first love, and so l hoped at some point I could cover it. I just didn’t think it would happen the way that it did.” He joined the club during the last week of Spring Training in 2022. “To go from helping out with Navy basketball coverage to then suddenly you’re in the clubhouse and you see Juan Soto and Josh Bell, it was very much a culture shock… I don’t think I talked to Juan Soto for the first month, I was so starstruck.” When I spoke to Golden last week, he took me through the nuts and bolts of the job, and humored me when I asked questions like whether it was possible for a beat reporter to be an introvert.

For Golden, 24, a normal day on the beat starts at 9 a.m., earlier if it’s a Sunday. The first thing he does is go over the previous day’s game. “I typically like to look back at the night before and see the big trends,” he said. “Obviously, when you’re writing on deadline, there are certain things that you might miss because you need to type or something happened in the late innings that maybe you missed. So I typically like to go back and look at the night prior and do some studying… I go back and look at Baseball Savant. Does anything stand out? Did this pitcher utilize one pitch more than he normally does? Those sorts of things. What trends did I miss?” He’ll also catch up on the previous day’s news at each level of Washington’s farm system and read whatever might have been written about the Nationals or their players from other news outlets. For the first of several times throughout the day, he’ll consult with his editors about what he’s working on now and what he might work on next.

Most importantly, he’ll research and write. In addition to writing game stories, beat reporters write everything from statistical deep dives to profiles of coaches and players to breaking news about the business side of the game. At 5:12 on Friday morning, the Post published an article Golden wrote about how Trevor Williams has succeeded by using his four-seamer less often. On the day we spoke, he mentioned that he was researching Luis García Jr.’s recent success at the plate. If all that sounds like a lot, well, it is. Later in the interview, I had to circle back and make sure that I understood the logistics of, specifically, at what point of the day Golden has time to do normal person things like go to the store. The answer: whenever he finishes all of the work above. “I get normal things done,” he laughed. “There is that free time, that flexibility during the morning, definitely. I promise I have groceries in my fridge.” For that reason, he dreads 4:00 p.m. games, which don’t leave time to do anything either before or afterward. “I love 1 o’clock games or 7. You know you’re going to have the front or the back end free, but 4 o’clock is right smack in the middle.”

It’s not always feasible, but for a typical 7 p.m. game, Golden prefers to get to the ballpark at 1:45. The clubhouse opens to reporters at 3, and until then he writes down questions he’d like to ask and keeps an eye on the field. “I like to be there early. Sometimes you’ll see a guy on the field doing something and it might pique your interest.” At 3, he goes down from the press box to the clubhouse. “It’s open for 45, 50 minutes, so that’s your time to talk to players, talk to front office people if they’re there, talk to whoever’s around.” Reporters are only allowed in certain parts of the clubhouse. Places like the kitchen, training room, and bathroom are off limits. Some parts Golden has never seen even once. “There’s two sections,” he said, “an office area and a coaches’ locker room area where we’re not really allowed. And there’s a back section we’re not allowed either, and I truly can’t tell you what’s back there.” Manager Davey Martinez talks to reporters at 4, and after that reporters go on the field to watch batting practice.

“You can still get players then if you want,” he explained. “If you can grab them coming off the field, that sort of thing. That’s typically when I like to talk to Darnell Coles, the hitting coach. The hitting coach is really busy, but I always know that he has to come off the field and walk past me, so I can get him when he’s coming off the field.” Golden laughed as he said the last part, but he explained that learning each player’s routines and figuring out how to be in the right place at the right time is actually a crucial part of the job. “I think that’s one of the things about the beat that people don’t realize. There’s definitely a rhythm to how things go. You know the relievers will always be around because they’re not doing a ton of prep work before the game… But starting pitchers are rarely around because they’re obviously going through their whole routine to get ready. And the hitters are kind of hit or miss. It depends on when they go to the cage and what their routine is. That’s one thing I didn’t know early on, like, ‘Oh, I want to talk to Josiah Gray.’ And Josiah was figuring out his routine and going through his stuff, and I was like, ‘Man, why is he never here?’ You have to kind of give these guys these moments and try to figure out what their routines are, and you build around that.”

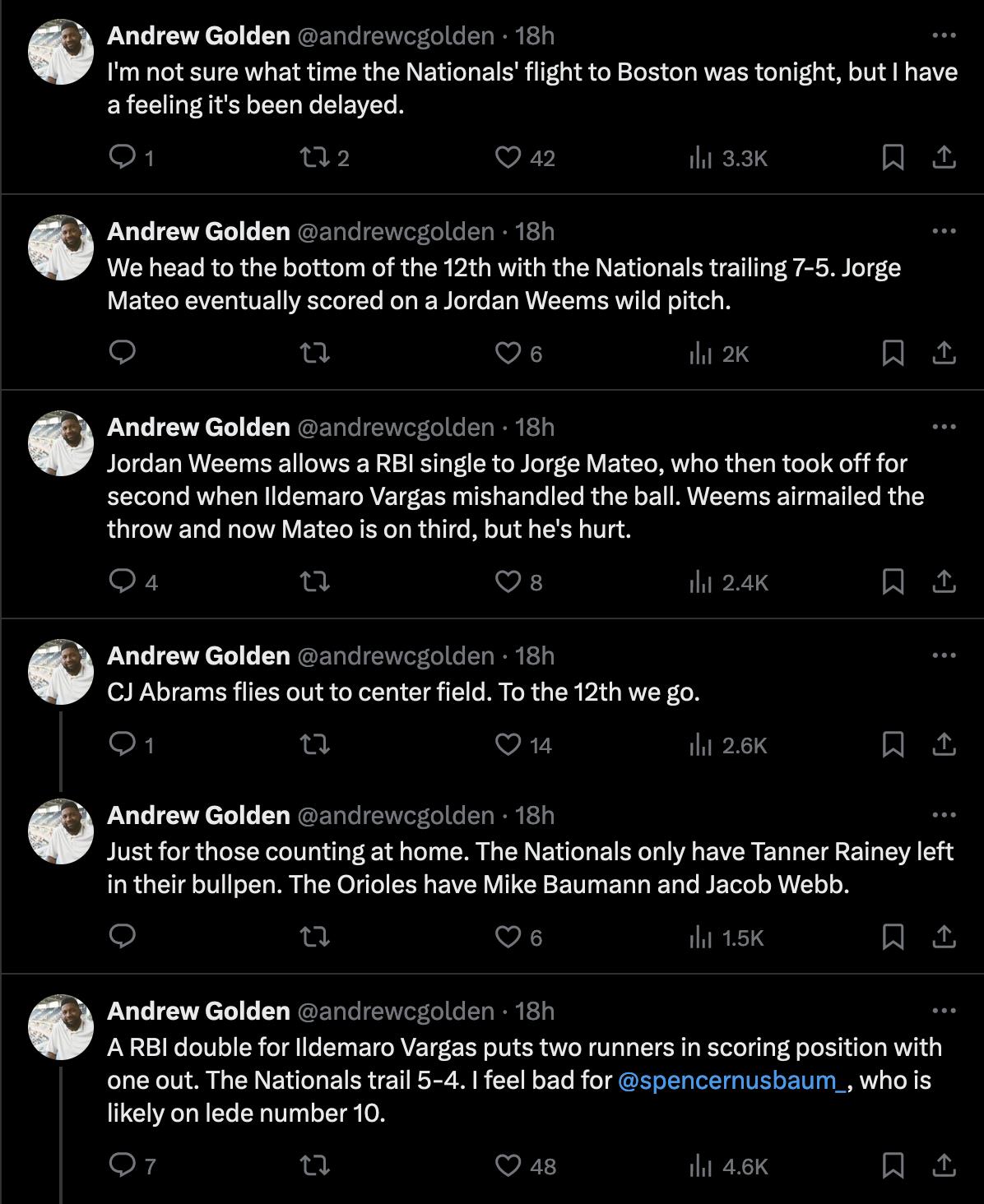

Once batting practice is over, reporters return to the press box to eat dinner before the game. For a night game, Golden’s 700- to 800-word game story is due when the final out is recorded, which means that he’s taking notes and writing throughout the game, then rewriting when new developments come up. “That was an adjustment too,” said Golden. “When do you start writing? Because obviously things can change. If somebody hits a go-ahead home run in the eighth inning, it can completely flip your story… Sometimes it just takes time to kind of develop that muscle and learn how to do that. I think that was a struggle at first, but then it starts to get a little bit easier, it starts to come to you a little more naturally.” Many beat writers also tweet the play-by-play throughout the game. Here’s a sample of Golden’s Twitter feed during last Wednesday night’s 12-inning affair between the Nationals and Orioles. Luckily for him, colleague Spencer Nusbaum was in charge of the game story that night.

As soon as their stories have been filed, reporters head back down to the clubhouse to hear from players and coaches again. “While we’re down there, our editors are editing the story,” said Golden. “And then we’ll come back up, and then we’ll add quotes in, and that’ll be the final story. So it’s probably an hour between when I file the first one and the second one.” At that point, the reporters finally get to go home or to their hotel, unless it’s getaway day. Golden generally prefers to go straight from the ballpark to the airport so that the next day, he can wake up in the city where he’ll be covering the game. I stammered a bit after Golden finished walking me through a normal day on the beat. It was a lot to take in. “So, so that’s — I mean, that’s a long day,” I said. “Yeah,” he said, laughing. “It is a grind. I’m sure people kind of know that, but I don’t think they know the extent. I mean, I have friends who are like, ‘Well, the game starts at 7. Don’t you get there at like 5:30?’”

It’s a grueling job: a month away from home during spring training, then a six-month-long season of days like the one described above, half of them on the road, with few days off. Knowing that, I asked Golden whether my impression of the beat writer demographic was correct. I’d noticed that beat writers tend to be either very young reporters or veterans who have been doing it forever because they’ve found a way to balance the lifestyle. “Yeah, that’s absolutely correct, at least from what I’ve seen,” he said. “I remember somebody telling me when I started, ‘Yeah, this is a job that you have when you’re single and have no kids’… You do it when you’re young, because it’s easier to manage a 162-game season when you don’t have all those other responsibilities, families, all that stuff.”

Golden recently got engaged, and the quirks of his job have been a part of the relationship from the very beginning. His first date with his now-fiancée was supposed to take place on the first Sunday of October 2022, but the Nationals and the Phillies needed to play four games in three days, all of them rain-soaked because a hurricane was bearing down on the east coast. Golden was texting her throughout the weekend, trying to explain the scheduling and scoring arcana that would determine whether he could make it or whether they’d need to reschedule. “It’s hard to explain how ridiculous it is. I’m trying to explain to her… we just have to get to the fifth inning and then we’re good. She’s like, ‘Why do you only need to get through half a game?’ There are so many things about baseball that we think are so normal that actually are not normal to normal people.” To make the grind more manageable, he now sends his parents and his fiancée an email every month with his entire travel itinerary, down to the flight numbers and hotels.

Golden mentioned another challenge to working the beat for an extended period of time: finding new ways to tell the same story. “I think when you first get started on the beat, everything feels new,” he said. “Coming up with ideas can be challenging when you’ve written stuff before. Trying to think, ‘How can I make this new?’ or ‘How can I make this different from before?’” As with any job, some days are harder than others. “There are some days where you just don’t have it. There’s just some days where you’re tired, you just got off a plane this morning and you drove to the stadium. And it’s day eight of a road trip and you’re like, ‘Man, I just don’t have it today.’ Those days definitely happen.”

All of this makes Golden more impressed by the veterans who have been doing it for years and years. “There are people who do balance both and who do this for a very long time. Mad props to them for that,” he said. “I can imagine trying to balance all those things, but it definitely is either younger people or people who have been doing this like 40 years and really know the business, know everybody in the business, and know the organization. The people who have institutional knowledge, it’s really interesting. One of our beat reporters is Mark Zuckerman [of MASN]. He’s been covering the team since 2005. He has an institutional knowledge that I just don’t have.”

That brought us to another important part of the job: Beat writers need to develop relationships with the people they’re covering. I asked Golden whether he has an easier time talking to players now than he did when he first started. “Definitely, yeah,” he said. “When you first join the beat there is a bit of — it’s not discomfort, but — I guess discomfort is the right word. They don’t really know you, you don’t really know them, and now you’re developing trust with them.” The most important thing is putting in the time, especially on road trips. “When you travel, and they realize that you’re traveling with them a lot and they see you on the road a lot, you’re going through the ride with them. I think they start to respect you more and they start to open up more, because they also understand you are going to be around.” Traveling and befriending writers in other cities has also made that easier. For example, when the Nationals signed Eddie Rosario, Golden asked Justin Toscano, who covered Rosario for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, for advice on how to connect with him. He also traded notes about Jeimer Candelario and Nick Senzel with Charlie Goldsmith of the Cincinnati Enquirer, which was easy because Goldsmith also happened to be Golden’s college roommate.

Golden mentioned several other ways to build trust with players. When they see you keep your word about not printing off-the-record comments, they start to trust that you’re not there to make them look bad. Similarly, they appreciate when a writer strikes the right balance when someone’s struggling. Some of the Nationals follow Golden on social media, where it is sometimes his job to talk about what’s going wrong with the team. “It can be a little bit awkward having to go to guys and be like, ‘Hey man, what happened there? Why’d you make that mistake?’ Or, ‘What was going through your mind?’ It can be awkward, uncomfortable. Nobody wants to ask about failures.” Managing to tell the truth respectfully makes a difference. “As long as you’re fair, and you’re not attacking them personally, I think people can respect that… I think a lot of times, people think the players will get upset if you say something negative. But I also think if you pretend like everything is positive and going well, I think they get upset with that too. Where the guy is 2-for-40 in his last 10 games, and you’re like, ‘What do you think you’re doing well at the plate right now?’ And they don’t want to hear that… You don’t want to personally attack somebody or say something negative about them as a person. But I also do think there’s a balance. You want to be honest with where they’re at. And if they get upset with your honesty, you have to live with that.”

Toward the end of the conversation, I asked Golden what people might not understand about his job. He mentioned the hours and the various unseen aspects, but he also talked about the perspective that comes from doing it day in and day out, and the way that all of his research allows him to ask the right questions. “Having to know the ins and outs of the team, and thinking critically about every roster move. What does this mean? Even just now, Robert Garcia just returned from a rehab assignment, and then Matt Barnes got DFA’d. And what does it mean? What does it mean for Tanner Rainey? I think my first year, I was not thinking like that. Now, your brain naturally goes like that. It’s an odd thought, like, ‘Man, my brain moves like this now?’ But there’s a lot of thought that goes into this.”

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/what-its-like-to-be-a-beat-writer/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions