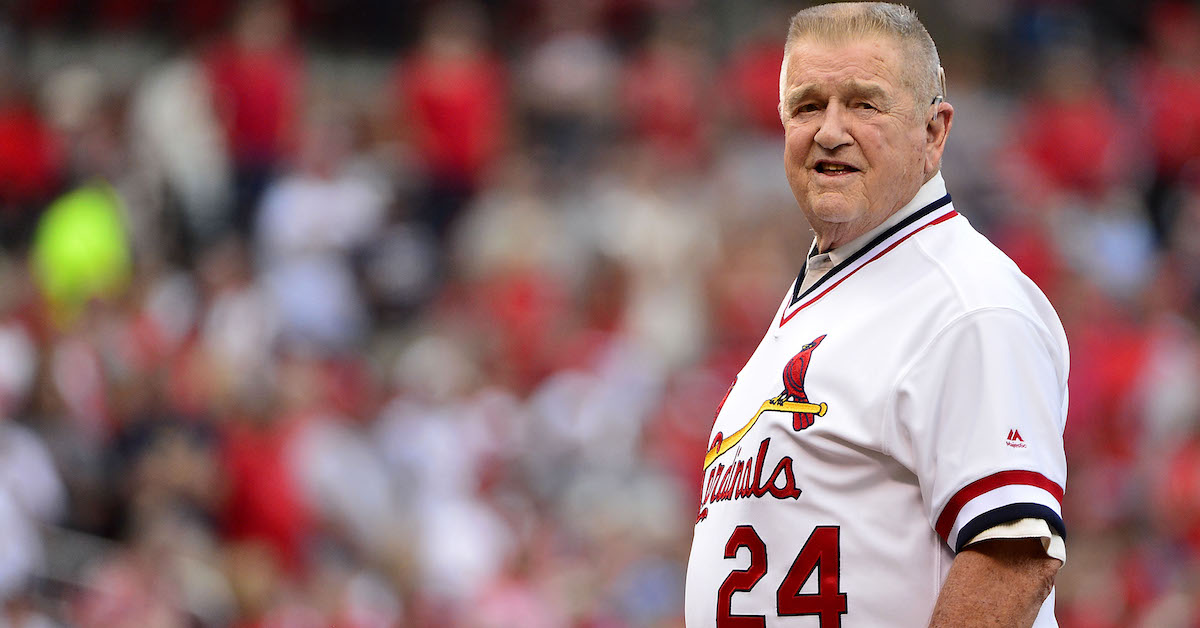

Jeff Curry-USA TODAY Sports

No manager defined the era of baseball marked by artificial turf and distant outfield fences as Whitey Herzog did. As the manager of the Royals (1975–79) and Cardinals (1980, ’81–90) — and for a short but impactful period, the latter club’s general manager as well — he assembled and led teams built around pitching, speed, and defense to six division titles, three pennants, and a world championship using an aggressive and exciting brand of baseball: Whiteyball. Gruff but not irascible, Herzog found ways to get the most out of players whose limitations had often prevented them from establishing themselves elsewhere.

“The three things you need to be a good manager,” he told Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite in 1981, “are players, a sense of humor and, most important, a good bullpen. If I’ve got those three things, I assure you I’ll get along with the press and I guarantee you I’ll make the Hall of Fame.”

Herzog was finally elected to the Hall in 2010, an honor long overdue given that he was 20 years removed from the dugout and had never been on a ballot. He passed away on Monday in St. Louis at the age of 92.

Herzog’s career in baseball spanned 45 years, from 1949 until ’94, and included eight years as a major league outfielder (1956–63) plus 13 full seasons and five partial ones as a manager (1973–90) as well as time as a scout, coach, director of player development, and GM — a résumé whose depth spoke to the levels of insight that he brought to the game. He had a keen eye for talent, and one undersold aspect of his career was his pivotal role in building the Mets’ 1969 champions and ’73 pennant winners as their director of player development from 1967–72. If not for an ill-timed remark, he might have succeeded Gil Hodges as Mets manager.

“Whitey was the boldest man in baseball,” wrote Bill James in his essential Guide to Baseball Managers, within which he noted Herzog’s penchant for platoons and odd defenses, reliance upon his benches and bullpens, and his appreciation for speed as an asset on both sides of the ball. James later summarized Herzog’s aggressive approach: “Let’s take charge of this game, let’s make this game as hard as possible for the other team, let’s force the action, put pressure on them, and make them lose.”

Calling him “Our Casey” — in reference to Stengel, who mentored Herzog when he was an outfielder in the Yankees’ chain — in an oft-reprinted 1990 profile, the Washington Post’s Thomas Boswell wrote, “Everybody in baseball says the same three things about Whitey Herzog: He’s the best manager in baseball or else the first name mentioned on a very short list. He’s the most abrasively self-confident and outspoken executive in the sport. And, whether he’s in the middle of a controversy or a pennant race, he seems to have a better time than everybody else.”

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog was born on November 9, 1931, in New Athens, Illinois, a village about 30 miles southeast of St. Louis. He was the second of three boys born to Edgar and Lietta Herzog; his father worked at the the Mound City Brewery, while his mother worked in a shoe factory. As a youngster, Herzog would sometimes skip school and hitchhike to Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis to watch the Cardinals or the Browns, and to collect batting practice balls to sell or play with. “Relly” — his nickname at the time — played baseball and basketball at New Athens High School; as a left-handed pitcher, first baseman, and outfielder, he earned second-team all-state honors and helped New Athens to the state championship game.

Though he drew interest from nearby colleges, Herzog instead signed with the Yankees in 1949, the same year as Mickey Mantle. He played for five years in the Yankees’ system, interrupted by a 1952-54 stint in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. While stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, he got his first taste of managing, piloting the base’s team to the Fifth Army championship and once beating a Fort Carson, Colorado team managed by Billy Martin.

Though Herzog never played a regular season game for the Yankees, Stengel took a shine to him during the team’s spring rookie camp. During his Hall of Fame induction speech, Herzog attributed the manager’s interest to a belief that he was the grandson of infielder Buck Herzog, a contemporary during Stengel’s playing days. “Casey and I used to sit in the press room during spring training and every night we would have a few pops and talk baseball, amongst other things… For some reason he knew that I was going to be a big-league manager.”

In that speech, Herzog recounted Stengel’s advice for how to deal with the media while managing a bad ballclub:

“You feed them and you drink with them and you stay up all night with them having a few pops. Put them to bed about 4:30 and by the time their deadline comes, they won’t even put the score of the game in.”

Herzog absorbed Stengel’s lessons on strategy as well. “I’ll bet Casey Stengel walked me down the third-base line 75 times a day teaching me that good base running boils down to anticipation and knowledge of the defense… You can steal a lot of runs,” he told the New York Times’ Richard Sandomir in 2010.

During his time in the Yankees’ organization, the towheaded Herzog acquired an indelible nickname based on his resemblance to Yankees pitcher Bob Kuzava, known as “The White Rat.” Various sources credit the observation to a local sportscaster covering the McAlester Rockets, the Class D affiliate with which Herzog started his professional career, and to Johnny Pesky, who coached Herzog with the Denver Bears in 1955.

Stocked in the outfield, in April 1956, the Yankees sent Herzog to the Washington Senators as the player to be named later, completing a seven-player deal centered around pitcher Mickey McDermott and giving the 24-year-old his big league shot. As the regular center fielder for a team that lost 95 games, he hit .245/.302/.337, then spent much of 1957 back in Triple-A, and in early ’58 was sold to the Kansas City A’s. He evolved into a useful platoon outfielder, hitting .268/.383/.384 (109 OPS+) in parts of three seasons for Kansas City and performing similarly in two seasons with the Orioles after being included in a six-player deal in January 1961. Slowed by an inner ear virus in 1963, Herzog played sparingly for the Tigers, then retired as a player. He finished his career with a .257/.354/.365 (97 OPS+) line, 25 homers, and 2.5 bWAR in 634 games.

In 1964, A’s farm director Hank Peters offered Herzog a scouting job at $7,500 a year. “I signed 12 players for $120,000 and seven of them eventually made the major league roster,” Herzog told Sports Illustrated’s Steve Wulf in 1982. “The best was Chuck Dobson, the pitcher. I could have had Don Sutton for $16,000, but Charlie Finley wouldn’t give me the money.”

After serving as a coach in 1965 under managers Mel McGaha and Haywood Sullivan, Herzog quit when Finley wouldn’t offer him more money, either. “You can take your damn mule and make him your coach,” he told the notoriously miserly owner.

Thanks to a recommendation from former Cardinals GM Bing Devine, who knew Herzog from the St. Louis area, he spent 1966 as the Mets’ third base coach under manager Wes Westrum. While his own contemporary estimate of the position’s value was comically inflated (“A good third-base coach can win 16 or 17 games a season for his club,” he told the New York Times in 1966), he had distilled Stengel’s advice, explaining, “When a base runner has a chance to score, you’ve got to remember that the percentage is with him. It’s like being a gambler — you’ll force the other side to make either a perfect play or a damaging mistake.”

A year later, Herzog was promoted, becoming the director of player development. While in that capacity, the team drafted a couple of key contributors to the 1973 pennant winners in Jon Matlack (the 1972 NL Rookie of the Year) and John Milner, and Herzog helped advance the careers of players such as Nolan Ryan, Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, and Wayne Garrett, all of whom contributed to the ’69 champions, plus Amos Otis and Ken Singleton, both of whom would attain stardom after being traded away. He even managed several of those players on the Mets’ 1967 Florida Instructional League team. During the Mets’ 1969 victory party, Hodges thanked Herzog, telling him, “For three years, whenever I called you for what I needed, you got me the right players.”

Herzog was viewed as the heir apparent to Hodges, but after the sudden death of the Mets manager from a heart attack on April 2, 1972, things didn’t unfold as expected. Mets chairman M. Donald Grant — whose name would later become mud in Queens for trading Tom Seaver — not only bypassed Herzog in favor of Yogi Berra, but also ordered him not to attend Hodges’ funeral “just so there wouldn’t be speculation that I’d be hired as the new manager,” Herzog told author Peter Golenbock. The chairman bore a grudge after word had gotten back that Herzog had once said, “M. Donald Grant doesn’t know beans about baseball!”

Herzog soon received his first major league managerial posting by resigning from the Mets in November 1972 to accept a three-year contract to manage the Rangers, replacing Ted Williams, who had advised Herzog of his pending retirement and suggested he throw his hat in the ring. The 40-year-old Herzog took over a team that had gone 54-100 in the strike-shortened season, its first since moving from Washington, D.C. to Arlington, Texas. Immediately tapping his reserve of humor, he suggested at his introductory press conference that he might also coach third base, “But if they hit like they did last year, I won’t have anything to do over there.”

As chronicled in Mike Shropshire’s hilarious account of the mid-1970s Rangers, Seasons in Hell, Herzog had to draw from that wellspring to endure the frustrations of a team in transition from veterans to youngsters — and one with a meddlesome owner, Bob Short. After drafting Houston high school pitcher David Clyde with the first pick in 1973, Short insisted that the 18-year-old lefty begin his professional career in the majors in order milk his potential as a gate attraction. The move took place over Herzog’s objections, and while it initially worked — Clyde won his debut despite walking seven in five innings — he wore out in August and finished with a 5.01 ERA.

By that point, he was no longer Herzog’s problem. Short coveted Martin, who by then had managed both the Twins and Tigers to division titles and was still on the job in Detroit; at one point he told Herzog, “I’d fire my grandmother to hire Billy Martin.” When the Tigers fired Martin on September 2, allegedly for ordering his pitchers to throw loaded-up pitches at Cleveland in protest of the umpires not ejecting Gaylord Perry for doing the same thing, Short made his move, firing Herzog, whose team was 47-91, and hiring Martin. “I thought I was hired to build more for next year than to win this year,” said Herzog at his exit interview. “I guessed wrong and I got fired.”

Declining a job in player development with the Rangers, Herzog spent most of 1974 as the Angels’ third base coach, serving as interim manager for four games between the firing of Bobby Winkles and the hiring of Dick Williams. He remained on staff into the 1975 season, until Royals GM Joe Burke reached out in late July, needing a manager after firing Jack McKeon, who had guided the 1969 expansion team to 88 wins in ’73 and had them at 50-46 thus far in ’75. As GM in Texas, Burke had hired Herzog, then resigned when he was fired; here he hired him again.

The Royals had drafted and developed an impressive core of young players centered around 22-year-old third baseman George Brett, 24-year-old righty Dennis Leonard, and 25-year-old righty Steve Busby, with astute acquisitions from elsewhere such as the 28-year-old Otis, a center fielder, 26-year-old first baseman John Mayberry, and 29-year-old left fielder Hal McRae. Within a few weeks, Herzog moved Brett from sixth to third in the batting order and replaced aging second baseman Cookie Rojas with 24-year-old Frank White, a light hitter but a slick fielder and a speedster who emerged as an exemplar of Whiteyball. The team went 41-25 on Herzog’s watch, finishing second in the AL West, then won three straight division titles — the franchise’s first taste of success — from 1976–78 by going 90-72, 102-60, and 92-70. With Herzog emphasizing a speed-and-defense style of play well suited to Kauffman Stadium’s artificial turf, Brett won his first of three batting titles (edging out McRae) and made his first of 13 All-Star teams in 1976; White won his first of eight gold Gloves in ’77 and made his first of five All-Star appearances in ’78; McRae became one of the first star designated hitters; and Leonard developed into a Cy Young contender and staff workhorse. (Busby, alas, was never the same after becoming the first active pitcher to undergo rotator cuff surgery in 1976.)

Unfortunately, the Royals lost three straight ALCS to the Yankees, the first two of which took place with Martin — who got himself fired in Texas so as to make himself available to the Yankees — at the helm and were decided in the ninth inning of winner-take-all Game 5s. They lost in 1976 when closer Mark Littell served up a walk-off home run to Chris Chambliss, and in ’77 after Herzog benched Mayberry, who had shown up late and in no condition to play, then dropped a pop-up that led to an unearned run in a Game 4 defeat. “The man couldn’t even talk, and I knew what was wrong… It must have been a hell of a party,” Herzog wrote in The White Rat, his 1987 memoir. In Game 5, Herzog started John Wathan at first base over the protests of other players, who believed Mayberry still gave the team the best chance to win; Wathan and reserve Pete LaCock went hitless, and then a faltering Leonard, Larry Gura, and Littell surrendered three runs in the ninth in Game 5, turning a 3-2 lead into a 5-3 defeat.

Blaming Mayberry — who after finishing as runner-up in the 1975 AL MVP voting had turned in two below-average seasons — for the defeat, that winter Herzog demanded the first baseman be traded. He was eventually sold to the Blue Jays just before the 1978 season opened in order to make room for phenom Clint Hurdle. With Hurdle and fellow rookies Willie Wilson, a left fielder, and shortstop U L Washington getting regular play, the Royals outlasted the Angels and Rangers in a three-way race, but fell to the Yankees in a four-game ALCS.

The Royals declined to 85 wins in 1979 as Herzog clashed with Burke over personnel moves and owner Ewing Kauffman over never having been offered more than a one-year contract. Meanwhile, some veterans resented Herzog’s handling of the Mayberry situation. Fired after the season ended, Herzog criticized Burke for not doing so sooner as a means of sparking the team.

Herzog started the 1980 season at home. At one point he was rumored to be replacing Red Sox manager Don Zimmer, but no call came until the 18-33 Cardinals fired manager Ken Boyer on June 8. Herzog signed a contract through 1982 and said at his introductory presser, “I’m gonna take this dang team and run it like I think it should be run.” The Cardinals went 38-35 on his watch before Herzog was promoted to GM, replacing John Claiborne, with Red Schoendienst stepping into the dugout on an interim basis. “I can do more for the Cardinals as GM than as field manager,” said Herzog of the promotion.

Though they had the league’s most potent offense in 1980, the Cardinals were awful at run prevention, and not fast enough for Herzog’s tastes given Busch Stadium’s turf and cavernous dimensions (414 feet to center field, 330 down the lines). In his two winters as GM, he would reshape the roster to suit his preferences, and thereafter push the team’s GMs in that direction. His clubs weren’t always successful, particularly on the pitching side (they were perennially near the bottom in strikeout rate), but his offenses were dynamic and entertaining — and, as Joe Sheehan pointed out in his newsletter tribute to Herzog, driven by high on-base percentages, which weren’t appreciated in that era the way they are today.

Cardinals NL Rankings 1980–90

| Year |

W |

L |

Finish |

RS/G |

RA/G |

|

HR |

SB |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS+ |

|

Def Eff |

| 1980* |

74 |

88 |

4 |

1 |

11 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

| 1981 |

59 |

43 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

| 1982 |

92 |

70 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

12 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

6 |

2 |

| 1983 |

79 |

83 |

4 |

5 |

10 |

12 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

7 |

| 1984 |

84 |

78 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

8 |

6 |

11 |

8 |

7 |

| 1985 |

101 |

61 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

| 1986 |

79 |

82 |

3 |

12 |

3 |

12 |

1 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

2 |

| 1987 |

95 |

67 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

12 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

9 |

10 |

8 |

| 1988 |

76 |

86 |

5 |

11 |

9 |

12 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

12 |

11 |

9 |

| 1989 |

86 |

76 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

12 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

| 1990** |

70 |

92 |

6 |

11 |

8 |

12 |

2 |

7 |

8 |

11 |

11 |

9 |

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

Yellow = won NL East title. * = Herzog managed 73 games. ** = Herzog managed 90 games.

Also underappreciated was Herzog’s successful pursuit of the platoon advantage. He generally had at least four switch-hitters in the lineup, with five in 1985 and sometimes six in ’87. Via Baseball Reference, his offenses (including the Royals and Rangers) had the platoon advantage 68.7% of the time during his career, the highest of anybody with at least 600 games managed during the 1973–90 window (Gene Mauch and Davey Johnson both had about 65%). The major league average over that span was 58.7%, putting Herzog at 119 in Platoon%+ — a stat B-Ref’s Adam Darowski and Kenny Jackelen helped to realize for this nugget (thanks, gents).

At the December 1980 Winter Meetings, Herzog went on a legendary spree. On December 7, he signed free agent catcher Darrell Porter, who had bolstered the Royals during his Kansas City tenure by making two All-Star teams (plus a third in 1980). On December 8, he and McKeon — “Trader Jack,” now the Padres’ GM — swung an 11-player deal in which the Cardinals acquired ace reliever Rollie Fingers and catcher/first baseman Gene Tenace. On December 9, he traded Leon Durham, Ken Reitz, and a player to be named later to the Cubs in exchange for another ace reliever, Bruce Sutter. Dealing from strength, he flipped Fingers to the Brewers along with pitcher Pete Vuckovich and catcher Ted Simmons in exchange for a four-player package that included pitcher Dave LaPoint. He’d clashed with Simmons, believing he could no longer control the running game and would serve the team better at first base, though that would have meant moving three-time Gold Glove winner Keith Hernandez to the outfield.

Not all of those deals panned out; the Milwaukee one gave the Brewers both the 1981 and ’82 AL Cy Young winners in Fingers and Vuckovich, with LaPoint the only one of the four newcomers whose long-term contribution with St. Louis was substantial. But the Cardinals were a better team for his efforts. With Herzog returning to the dugout in a dual manager/GM role, they compiled the NL East’s best record in 1981 at 59-43, but in the strike-torn season missed the playoffs by finishing second in both the pre- and post-strike halves. Despite a 7-2 closing run in the second half, they wound up half a game (yes) behind the Expos.

Herzog not only remained active that offseason but had even more success with his trades. In October he dealt reliever Bob Sykes to the Yankees for switch-hitting minor league outfielder Willie McGee. Sykes never pitched in the majors again while McGee would go on to win two batting titles and an MVP award for St. Louis. In November Herzog traded away pitchers Silvio Martinez and Lary Sorensen (from the Brewers trade) in a three-team deal that yielded outfielder Lonnie Smith. At the Winter Meetings, he traded outfielder Sixto Lezcano (another from the Brewers deal) and two-time All-Star shortstop Garry Templeton to McKeon’s Padres as part of a six-player deal that brought All-Star shortstop Ozzie Smith to the Cardinals. Though still just 25 years old, Templeton had worn out his welcome in St. Louis; Herzog suspended him without pay for three weeks after he gave hometown fans the finger and grabbed his crotch after they booed him for not running out a dropped third strike. Earlier, Templeton had complained about being too tired to play day games after night games. The suspension was lifted after Templeton agreed to see a psychiatrist, was diagnosed with depression, and was given medication, but the bridge was burnt. “Templeton doesn’t want to play in St. Louis, he doesn’t want to play on artificial turf, he doesn’t want to play in Montreal, he doesn’t want to play in Houston, he doesn’t want to play in the rain,” Herzog said. “The other 80 games, he’s all right.” Templeton made one more All-Star team in a career that lasted another decade, while Smith made 14 as a Cardinal, becoming a St. Louis icon and a Hall of Famer.

Herzog stepped down as GM just as the 1982 season began, but the team he built flourished, winning 92 games and the NL East, their first success since the advent of division play in 1969. The offense’s 67 homers ranked last in the NL, with only Porter and George Hendrick reaching double digits, but their 200 steals led the league; eight players reached double digits, with Lonnie Smith’s 68 propelling him to a second-place finish in the NL MVP voting. Ozzie Smith made his second All-Star team, McGee finished third in the NL Rookie of the Year race, and Sutter third in the NL Cy Young race. In their first playoff appearance since 1968, the team swept the Braves in the NLCS, then beat the Brewers — featuring Vuckovich and Simmons (Fingers was injured and missed the series) — in a seven-game World Series. Porter became the second player to win both LCS and World Series MVP honors in the same season.

The Cardinals receded to 79 wins in 1983. On June 15, GM Joe McDonald traded Hernandez to the Mets for pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. As a baseball move, this one was lopsided in favor of New York, but Herzog and Hernandez hadn’t gotten along, and the manager was already aware of the first baseman’s cocaine usage. During the 1985 Pittsburgh drug trials, Hernandez confessed that he used cocaine with teammates Joaquin Andujar, Lonnie Smith (who voluntarily entered rehab in mid-1983), and Sorenson. That year, Herzog estimated that 11 of his Cardinals players were “heavy users” in the early ’80s and said he believed cocaine had cost him a championship with the Royals.

After a mediocre 1984, the Cardinals won 101 games in ’85 despite having just one player reach 20 homers: first baseman Jack Clark, acquired from the Giants in February in exchange for LaPoint, outfielder David Green (another player from the Brewers deal), and two other players. The team’s 87 homers ranked second to last in the NL, but St. Louis again led with 314 steals, with rookie left fielder Vince Coleman stealing an NL-high 110; the Cardinals led in scoring as well while ranking second in run prevention. McGee won the NL batting title and MVP honors, hitting .353/.384/.503 (147 OPS+) with 18 triples and 56 steals, while Andujar and newly acquired lefty John Tudor each notched 21 wins and respectively placed fourth and second in the Cy Young voting behind Dwight Gooden.

The 1985 season marked the first in which the two championship series were expanded from best-of-five to best-of-seven. Facing the Dodgers, the Cardinals lost the first two games in Los Angeles, and lost Coleman to a fractured left leg in a bizarre mishap with Busch Stadium’s automatic tarp. St. Louis nonetheless stormed back to win in six thanks to some late-inning heroics. In Game 5, switch-hitting Ozzie Smith — who to that point had never homered off a righty in over 3,000 career plate appearances — hit a walk-off solo homer off Dodgers closer Tom Niedenfuer to push the Cardinals to a three-games-to-two lead. In Game 6 back in L.A., the Dodgers carried a 5-4 lead into the ninth, but the Cardinals put two on base against Niedenfuer. With two outs and runners on second and third, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda bypassed the opportunity to intentionally walk the right-handed Clark (.281/.393/.502, 149 OPS+ that year) and summon a lefty to face lefty Andy Van Slyke (.259/.335/.439, 116 OPS+) or force Herzog to go to his bench to gain the platoon advantage. Instead, Niedenfuer faced Clark, who drilled his first pitch for a three-run homer that proved decisive.

The so-called “I-70” World Series pitted the Cardinals against the Royals, now managed by Dick Howser and still featuring Brett, White, Wilson, McRae, and Dan Quisenberry in prominent roles as well as young starters Bret Saberhagen and Danny Jackson. The Cardinals won the first two games on the road, and after losing Game 3, took Game 4 as well, with Tudor notching his second victory of the series. Jackson’s five-hitter in Game 5 staved off elimination and sent the series back to Kansas City. With the Cardinals’ Danny Cox and the Royals’ Charlie Leibrandt both pitching masterfully, Game 6 remained scoreless until the eighth, when St. Louis scratched out a run on two singles and a walk. The Cardinals took that lead into the bottom of the ninth when all hell broke loose.

Pinch-hitter Jorge Orta led off by hitting a slow bouncer to the right side of the infield, where a charging Clark fielded the ball cleanly and threw to pitcher Todd Worrell covering first. The throw beat Orta, who tripped over the base, but umpire Don Denkinger called him safe. Replays showed he was out, but with no challenge system in place, Herzog argued to no avail.

Another single, a forceout at third, a passed ball, and an intentional walk loaded the bases, and then ex-Cardinal Dane Iorg singled home pinch-runner Onix Concepcion with the winning run, sending the series to Game 7. Realizing Denkinger would work the plate in the final game, Herzog sounded beaten already, saying beforehand, “We got about as much chance of winning as a monkey.” Pitching on three days of rest for the fourth time that month, Tudor was chased in the third inning after allowing five runs, and both Herzog and Andujar were ejected for arguing balls and strikes. Saberhagen went the distance for a five-hit shutout and an 11-0 win.

Disliking the abuse Denkinger took for missing the call, Herzog later made his peace with the umpire. In 2005, commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Cardinals’ pennant, he invited Denkinger to speak at a fundraiser benefitting his charitable foundation.

With Clark limited to 65 games due to a torn ligament in his right thumb, the Cardinals slipped to 79-82 in 1986 thanks to an offense that was the NL’s worst. Both he and the team came back strong in 1987 as he hit 35 homers and led the NL in walks, OBP, SLG, and OPS+, but he severely sprained his right ankle on September 9 and was limited to a few pinch-hitting appearances thereafter. The Cardinals won 95 games and the NL East, then overcame a three-games-to-two deficit to defeat the Giants in a seven-game NLCS, but Clark pinch-hit once and was left off the roster for the World Series against the Twins.

Under Tom Kelly in his first full season as manager, the Twins had gone just 85-77 before upsetting the 98-win Tigers in the ALCS, but in addition to not having to face Clark, the Twins had one other advantage: the Metrodome, where they had gone 56-25 as their fans’ high-decibel cheering unnerved opponents, and where they would play four of the series’ seven games, since home field advantage alternated between leagues rather than depending upon won-loss records. The home team won every game of the series, with the Twins outscoring the Cardinals 33-12 at the Metrodome — and only Game 7 was close. After the Cardinals scored two runs off Frank Viola in the second inning, the Twins chipped away, going ahead for good in the sixth and winning 4-2.

That was the Cardinals’ last gasp at greatness under Herzog. For the third time during his tenure, they followed a pennant with a sub-.500 season, this time 76-86 and a fifth-place finish, their worst since 1978. They rebounded to 86 wins in 1989, but when the team started the ’90 season 33-47, a disgusted Herzog resigned.

He never managed again. Long friendly with Angels owners Gene and Jackie Autry, he returned to Anaheim as senior vice president and director of player personnel in September 1991. But while he thought he’d have complete control of baseball operations, he instead wound up in a power struggle with Dan O’Brien, the senior VP of baseball operations. It was an odd situation, particularly with Herzog given license to work primarily from his home in suburban St. Louis. The Angels went 72-90 in 1992, then 71-91 in ’93. In mid-September 1993, Herzog convinced the Autrys to fire O’Brien, thus consolidating his authority. But while his ability to spot talent remained intact — mainly in the form of not trading away the likes of Jim Edmonds, Tim Salmon, and other youngsters the Angels were developing — he was constrained by a budget cut, and had fallen behind the times in his dealing with his players and their agents, alienating them with his abrasive negotiating tactics. He resigned in mid-January 1994.

Following the 1996 season, Herzog rejected an offer to manage the Red Sox; the team instead turned to Jimy Williams.

Herzog finished his managerial career with a 1281-1125 record and a .532 winning percentage. He ranked 25th in managerial wins when he retired, which may help to explain why he wasn’t considered for Cooperstown until the 2010 Veterans Committee Managers and Umpires ballot. Up for election alongside contemporaries Johnson, Kelly, Martin, and Mauch as well as older candidates, and with both Lasorda and Dick Williams sitting on the committee, he received 14 of 16 votes. Umpire Doug Harvey, who received 15, was elected as well.

In the end, Herzog’s legacy went well beyond wins and losses. In the era of big hair and plastic grass, his teams were of their time, but like Stengel and contemporary Earl Weaver, he was well ahead of the curve, masterful in assimilating information and deploying it to his advantage. Long before the age of analytics, his hand-colored defensive charts were the stuff of legend. He understood his players’ strengths and how to place them in positions to succeed, the most timeless of qualities when it comes to managing a ballclub.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/whitey-herzog-defined-an-era-but-he-was-ahead-of-his-time/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions