© Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel/USA TODAY NETWORK

On Wednesday, the estimable and exquisitely coiffed Jeff Passan reported that MLB is considering a small change to the pitch clock for 2024. In its first year, the pitch clock counted down from 20 seconds with runners on base; MLB wants to bring that number down to 18 seconds. The proposal also includes a reduction in mound visits from five per team to four. MLB’s competition committee will deliberate over these proposals and then — considering more than half of the body is appointed by the league — most likely rubber-stamp them.

As for the headline change? It’s two seconds. It’s nothing. Two Mississippi. The Astros’ pitching staff alone has two Mississippi guys. (Okay, two Mississippi State guys.) MLB has already made the single biggest change it’s ever going to make to the timing of the game by instituting the pitch clock in the first place. How much can two seconds possibly matter?

I cannot imagine it’ll matter that much. If pitchers can deliver the ball within 15 seconds with the bases empty, surely they can do it within 18 seconds with baserunners on — especially in the age of PitchCom. If taking away the ability to vary delivery tempo reduces pitchers’ ability to control the running game, so much the better. We just spent all season freaking out over how cool the likes of Ronald Acuña Jr. and Corbin Carroll are; let them steal even more bases.

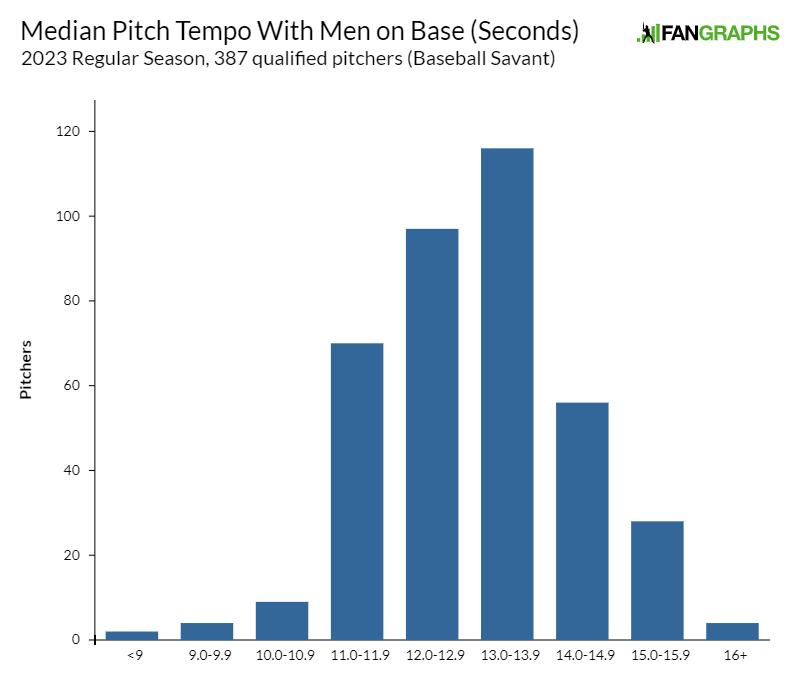

Most pitchers are going to be able to deal with this change without even noticing. Even with men on base, more pitchers took 10 or fewer seconds to deliver the ball than 16 or more.

This change would also only affect less than half of the pitches thrown in the majors next year. Between the 2023 regular season and playoffs, there were almost 730,000 pitches thrown; just 43.2% of them came with men on base, and that’s the highest ratio of any full season since the introduction of Statcast. In all likelihood, the most noticeable effect of this rule change will be that teams don’t have to replace the lightbulbs on the pitch clocks as frequently.

The introduction of the pitch clock and pickoff rules could not have been a more rousing success in its first year. MLB’s stated goal was to bring down game time, and that it did. MLB is unusual, as businesses go, in that the league wants there to be less of its product. We’re fortunate pizzerias don’t abide by a similar “less is more” philosophy.

The average big league game in 2023 lasted two hours and 42 minutes, down 24 minutes from 2022 and 29 minutes from 2021, the year a three-hour, 11-minute average time of game set a new all-time high.

This past spring, I took my six-year-old niece to her first baseball game, and at two hours and four minutes, it ended up being the shortest Phillies game in 11 years. Thank goodness, because we got the whole game in before my own lack of parenting experience (“Sure, you can eat that whole adult-size serving of ice cream on your own!”) caused any problems.

This season also featured a one-hour, 50-minute Nationals-Pirates game, the shortest major league contest in 13 years. All told, 14 games clocked in at two hours or less. Shaving 20-odd minutes off the game is nice. For people who work at the park in any capacity, or parents of young children, or season-ticket holders who just like to be in bed before 10 PM, it really does make a difference.

But it’s not just about knocking down the total run time of the ballgame; the pitch clock did wonders in terms of eliminating dead space, those agonizing still seconds between pitches with Craig Kimbrel or Giovanny Gallegos on the mound. It’s not just that the games were 15% or so shorter than before, it’s that the 15% that got cut was all fat; it came from the most boring, like, 20-25% of the game.

Eventually, though, we viewers adjusted. And so did the players:

Pitch Timer Violations by Month

| Month |

Games |

Pitcher Clock Violations |

Per Game |

| March/April |

425 |

203 |

0.48 |

| May |

415 |

165 |

0.40 |

| June |

390 |

116 |

0.30 |

| July |

367 |

99 |

0.27 |

| August |

411 |

88 |

0.21 |

| September/Oct |

421 |

76 |

0.18 |

On one hand, that’s good. Players figured out how to manage the clock pretty quickly. Pitchers ran afoul of the timer about once every other game in March and April; in September, that ratio was about one every six games. By midseason, you’d have to be in the park staring at the clock in center field in order to notice anything had changed.

But they also figured out how to game it. Catchers quickly cottoned on to the fact that it was better to burn a disengagement and call timeout with one second on the clock — like a quarterback looking at double zeroes on the play clock — than risk a violation or a rushed delivery. Hitters began using their own timeouts more routinely; the two-strike hitter timeout is almost a pro forma move now.

Here, we return to Passan’s report: The reasoning behind the tweak to the pitch clock is that games were stretching out over the course of the season. Games played in April and May clocked in at two hours, 37 minutes; games played in September were seven minutes longer, on average.

That’s because baseball players and coaches are both clever and highly motivated to play the game they want. Given enough time, they will find loopholes and weak points in the rules, and eventually further regulation will be introduced to bring the game back in line.

The putative reason for player pushback on the shortened pitch clock is that the game’s newly heightened tempo will lead to more pitcher injuries. Framing the issue this way paints proponents of a tighter pitch clock as insensitive, even anti-player.

To which I’ll say this: Goosing the tempo of the game makes pitching more physically arduous under the conditions the teams and players have created for themselves. From physical conditioning to pitch design to roster construction to in-game tactics, everything has been optimized for the max-effort, breaking ball-heavy one-inning reliever.

This method of player development and deployment is self-reinforcing. As standards increase for pitchers, the number of pitchers who can throw 200 above-average innings a year, turn over a lineup three times, pitch into the seventh inning of a playoff game… are there even 30 of those guys in the entire league now?

The more demanding the job gets, the more pitchers get hurt, and the more replacements must be created. And the best way to create a new useable big league pitcher is to stick him in front of an Edgertronic camera, teach him a slider, and tell him to go out there and throw like hell for 20 pitches at a time.

Of course pitchers are going to get hurt doing that. If you were asked to run a 5K, took off at a 400 meter pace, and got hurt halfway through the race, it wouldn’t mean that running was inherently dangerous. The rules have just disincentivized cultivating endurance, because with 13-man pitching staffs, you can stack up eight or nine grip-it-and-rip-it dudes in your bullpen and go an inning at a time.

I already mentioned one of the first and shortest games I went to this year, but let’s turn to one of the last and longest: Game 2 of the ALDS between the Orioles and Rangers. This was an 11-8 game that went three hours and 45 minutes, with 13 pitchers and five mid-inning pitching changes. Eight Orioles pitchers combined to throw 115 strikes out of 206 pitches, and issued 11 walks.

No pitch clock is going to speed the game up when both teams are bringing in a new reliever every five innings.

Legislating that out of the game would be a titanic challenge for MLB, if the league were even inclined to make such changes. It’s probably the thing I like least about the current major league on-field product, and if I were made dictator of the world, with carte blanche to change it, I do not know where I’d start.

An individual team, incentivized to win, will pursue that goal with total indifference to the entertainment product. That, on a philosophical level, is why game times started to swing back up next year. But until and unless something can be done about that, let’s shave another two seconds off the pitch clock in the meantime.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/clock-stock-and-two-smoking-seconds/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions