Gregory J. Fisher-USA TODAY Sports

The following article is part of Jay Jaffe’s ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2024 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, and other candidates in the series, use the tool above; an introduction to JAWS can be found here. For a tentative schedule, see here. All WAR figures refer to the Baseball-Reference version unless otherwise indicated.

It began with a torn labrum in my right shoulder, the result of a swimming pool mishap that ultimately sent me under the knife about six weeks before my 34th birthday and took whatever remaining gas there was out of my fastball. This is how I wound up in a shoulder sling in December 2003, first at the Winter Meetings in New Orleans and then with my family in Salt Lake City, watching the snow fall as everyone else went skiing.

I’d gone to New Orleans to meet several members of Baseball Prospectus, who had invited me to write something for them about the 2004 Hall of Fame ballot given the positive reception my expansive breakdowns of the previous two ballots had gotten at my own Futility Infielder blog. On January 6, 2004, I debuted at BP, introducing a metric cryptically called WPW (and soon WPWt, for WARP Weighted) that I defined as “an attempt to cobble together a simple, easy-referenced figure which considers both career and peak; it’s simply an average of the WARP3 and PEAK figures.” The astute reader will recognize this as the basic definition of JAWS, particularly on the occasion of my celebrating the 20th anniversary of the introduction of my Hall of Fame fitness metric. Welcome to the party!

Given this milestone, I thought it would be appropriate to take a look back, both to outline the metric’s history and to consider its impact. Two decades ago, I could not have imagined that JAWS would become such a prevalent yardstick in Hall of Fame voting, referenced by some of the most accomplished and respected writers in the industry and by numerous fans following along. Nor could I have imagined that I’d be among those voting, a full-time professional writer with 14 years of membership in the BBWAA as well as a book under my belt devoted to the topic of the Hall of Fame. It was my dumb luck to stumble into a topic about which many baseball fans not only felt passionate, but that renewed itself every year with the annual elections. Holy mackeral, as Vin Scully would say.

I had begun writing about baseball as a sidelight to my day job as a graphic designer of textbooks and children’s books. Most of my writing was pegged to current news or what I’d witnessed at the ballpark, but the Hall of Fame coverage — which had its foundation in my love of Bill James’ 1985 and 2001 Historical Abstracts, as well as his ’94 book about the Hall, The Politics of Glory — had particularly struck a chord, reaching thousands of readers instead of my usual audience of a few hundred thanks to it being featured on Baseball Primer (later Baseball Think Factory). I had broken down the 2002 and ’03 ballots using Win Shares, a value metric introduced in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract in the fall of ’01. Win Shares didn’t click with the statheads, given a methodology that was difficult to understand (a year later, James delivered a highly technical 700-page tome devoted to it), and some very odd choices, such as each Win Share representing one-third of a win, or a 52-48 split for pitching and defense versus offense.

In late 2002, Baseball Prospectus’ Clay Davenport introduced Wins Above Replacement Player (WARP), which estimated each player’s total value — offense, defense, baserunning — above that of a theoretical “replacement player,” a freely available minor league call-up. WARP used a lower replacement level than current formulations of WAR, said to be something on par with the abysmal level of play of the 1899 Cleveland Spiders (20-134, .130). I had sprinkled WARP3 (the version with historical adjustments to account for shorter 19th-century schedules and the improvement in leagues over time) into my 2003 Hall of Fame ballot analysis, but was somewhat taken aback by the way the metric’s low replacement level suggested that Brett Butler’s body of work (108.3 WARP3, including a whopping 434 fielding runs above average) made him a borderline Hall of Fame candidate. Thankfully, with better data and a better process, Davenport revised WARP in late 2003.

In my previous analyses, I had relied not only on Win Shares but upon James’ somewhat outdated Hall of Fame Standards and Hall of Fame Monitor metrics, neither of which accounted for park and league scoring levels or took note of defense beyond applying bonuses for a player’s position — adjustments we were now capable of accounting for via WARP. So as I sat there in my sling, I transcribed each Hall of Famer’s career batting, fielding, and pitching runs data as well as WARP into an Excel spreadsheet, calculating the averages at each position and then measuring the current candidates against those standards; at the time, I removed the worst player at each position, inevitably an outlier, from the calculations. Building upon an idea introduced in James’ first Historical Abstract and expressed in a few different ways in its follow-up, I calculated a player’s peak value as well, experimenting with a few different alternatives but settling on a player’s five best consecutive seasons, “compensating for war- or severe injury-related seasons by ignoring them completely or, in the case of Carlton Fisk, combining two half-seasons into a full one.”

The use of this more advanced data underscored — and better quantified — points that James had made in The Politics of Glory. As I wrote:

One thing, in looking over my spreadsheet and in considering the history of the Hall of Fame, is abundantly clear: the institution has been sullied by mediocre and inappropriate choices. Perhaps that’s simply a function of our vantage point, 67 years after the first election. Better equipment and better training have contributed to longer careers, a larger pool of players has elevated the caliber of play, and our ability to collect and process data about the game’s history and analyze it with sophistication has increased our knowledge and, hopefully, raised our expectations of what constitutes a Hall of Famer.

Thus what became central to the JAWS project was the identification of candidates who met or exceeded the standards, and the promotion of those candidates for election as a way of improving the institution (or at least not eroding it further). While WARP’s replacement level was still too low — candidates such as Andre Dawson, Dale Murphy, Jim Rice and Dave Parker all had WARP3 totals about 40-50 wins higher than their current WAR totals — my analysis showed that all of those players were below the standards at their position, some by a little and others by a lot. From among the candidates, I identified Keith Hernandez, Ryne Sandberg, Alan Trammell, and Paul Molitor as Hallworthy on the position player side, while tapping Bert Blyleven, Dennis Eckersley, Goose Gossage, and Lee Smith in the pitching follow-up published on January 14, 2004. My basis for touting all three relievers was the fact that only two were enshrined at that point, namely Hoyt Wilhelm and Rollie Fingers; it was time to flesh out a standard.

This was an opening salvo in the use of all-encompassing advanced metrics to sketch out Hall of Fame standards at each position. Its most startling finding — at least to its inventor — was that Blyleven was well above the bar set by the average enshrined starting pitcher, and that the more popular Jack Morris was significantly below it. The battle lines that would define the first decade(ish) of JAWS had been drawn. (Having recounted the blow-by-blow of those battles in The Cooperstown Casebook, excerpted at this very site, I’ll sidestep them here.)

The series was popular enough within BP and with its audience that I was encouraged to keep going; it turned out that people liked to read about the Hall of Fame, and not just during the winter, whether it was to think about which active players might be headed to Cooperstown, or which honorees were the most egregious choices. By the time I broke down the 2005 ballot, I had — with the encouragement of BP co-founder and editor Christina Kahrl — given the metric a catchy and very self-conscious acronym, JAWS, for Jaffe WARP Score. This was much more fun, as I could then cite the trailer of the famous shark movie: “It is as if God created the Devil and gave him… JAWS.”

“Like the famous cinematic shark, [it] generally elicits screams at the first hint of its approach,” I wrote years later.

By the time of the 2006 ballot, I had switched from my initial definition of peak to one that used a player’s best seven years at large, something that was apparently easier for Davenport to automate (I wasn’t about to re-transcribe from every card, and so I was dependent upon him for annual data queries). The choice of seven years wasn’t exactly scientific, but I found that it was a sweet spot for explaining the elections of many short-career players. The more years you lump into the peak score, the more it converges with career WAR, making it somewhat redundant.

I had also begun contributing regularly at BP outside my JAWS work, first for the Prospectus Triple Play series (monthly bullet-point tidbits about the Twins, Dodgers, and Giants) and then the Prospectus Hit List, a weekly power rankings that blended Davenport’s first-, second-, and third-order Pythagorean Standings. In mid-2007, I added a twice-weekly column, Prospectus Hit and Run, and basically made the leap to full-time writing. In December 2010, I was accepted into the BBWAA along with my BP colleague David Laurila.

For as much encouragement as BP and its audience gave me, the site’s paywall limited the reach of JAWS. What’s more, BP’s infrastructure and design were such messes, and money so tight, that it took years even to get a single leaderboard page that displayed career WARP leaders. In the entire time I was there, nobody built a leaderboard devoted to JAWS; it was all in my spreadsheet.

I don’t know the extent to which JAWS played a role in the January 2011 election of Blyleven, but it was something worth celebrating. Between my BBWAA membership, mentions from the likes of Joe Posnanski and Peter Gammons, and some sharing via Twitter, JAWS gained enough traction that in November 2011, MLB Network invited me to audition for its new Clubhouse Confidential show, hosted by Brian Kenny. In my debut on November 29, 2011, Kenny and I discussed the 2012 Golden Days Era Committee ballot, and particularly Ron Santo, Minnie Miñoso, Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, and Luis Tiant before turning our attention to Albert Pujols. “I love JAWS already,” said Kenny at one point in the segment (stay tuned for little FanGraphs-related Easter egg near the five-minute mark).

Less than a week later, Santo, whom I had begun championing within the Veterans Committee process in the spring of 2005, was elected to the Hall via that 2012 ballot. It was more likely an example of correlation rather than causation, but either way it was bittersweet, as Santo — just the 12th third baseman elected to the Hall — had died due to complications related to bladder cancer and diabetes just a year earlier.

I joined the Clubhouse Confidential rotation of sabermetric correspondents, which also included Rob Neyer, Dave Cameron, Joe Sheehan, and Vince Gennaro. This gave me a chance to use JAWS to break down the 2012 BBWAA ballot on television; for one two-part segment, Sheehan and I did a roundtable that also included Jon Heyman, who didn’t agree with our conclusions about Morris, to say the least.

In April 2012, Baseball Prospectus published Extra Innings, a sequel to the popular Baseball Between the Numbers, published five years earlier. Within the book, editor Steven Goldman gave me prime real estate in Part I to contribute two chapters. In “What Really Happened in the Juiced Era?,” I covered the way the ball itself and other factors besides performance-enhancing drugs had changed within the game to make home runs more prevalent. In “How Should the Hall of Fame Respond to the Steroid Era?” I covered the history of PEDs in baseball and introduced JAWS to a wider audience.

That same spring, I was invited to participate in a roundtable at the inaugural SABR Analytics Conference in Arizona, on a panel that included Neyer, Cameron, and Gennaro. It was there that I ran into Sean Forman, the founder of Baseball Reference and already a friend through online correspondence and past SABR conventions. In a brief conversation, I asked him if he’d be interested in working up a Baseball Reference WAR-based version of JAWS. He was enthusiastic about the possibility, though it wasn’t until September that we even touched base again on the topic. On November 14, 2012, WAR-based JAWS made its debut, with each player’s career, peak (WAR7) and JAWS not only on every player page but with the sortable positional rankings pages as well. To my view, moreso than putting the metric on TV or in a book, this was the point at which JAWS stepped into Technicolor. We weren’t in Kansas anymore.

By that point I had a new gig, writing a new daily blog called Hit and Run for Sports Illustrated’s website, starting in late May. Suddenly, my audience increased by at least an order of magnitude, and come time for the 2013 election, editor Ted Keith gave me free reign to expand my ballot roundups from a few hundred words per candidate in position-based breakdowns to bios of a couple thousand words, helping to place the advanced statistics in the context of each player’s history while also revisiting the career highlights and lowlights. In the cases of Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa — all new to the 2013 ballot, along with Craig Biggio, Mike Piazza, and Curt Schilling — those histories included a lot more to untangle with regards to PEDs. Nobody was elected that year, but on MLB Network and in print (or pixel), JAWS got attention from some heavy hitters within the industry who grasped the value of the metric in helping to triage their ballots.

When that phenomenon repeated during the 2014 cycle, an acquisitions editor at Thomas Dunne Books named Rob Kirkpatrick invited me to lunch and asked if I’d be interested in writing a book about the Hall of Fame. In fact, I had already sketched an outline when the powers within Baseball Prospectus suggested I do the same circa 2010, but the project was tabled because the money was negligible. I had a title and a catchy, sardonic subtitle that had been kicking around since 2007 based on a riff with BP’s Derek Jacques: The Cooperstown Casebook: Who’s in the Hall of Fame, Who Should Be In, and Who Should Pack Their Plaques. Over the next couple of months I wrote a book proposal that became “How Voters Put Third Base in a Corner,” a chapter detailing the position’s underrepresentation within the Hall, Santo’s career, and the battle to elect him.

After the 2013 election, I also served on an eight-member committee chaired by outgoing BBWAA president Susan Slusser that was tasked with studying the backlog on the ballot, as well as potential rule changes that might alleviate it. The committee was stocked with members who reflected a broad spectrum of viewpoints, ranging from “the system is fine” to “the system is broken.” Six of the committee members had the 10 years of service required to vote and a seventh (the late Jim Caple) was a couple years away; the eighth was me, the grunt with the spreadsheets. Via our middle-of-the-road proposal, we asked the Hall’s board of directors to expand the ballot from 10 slots to 12. They tabled the request into oblivion, and instead instituted a rule sunsetting honorary voters; they had already put a rule into place the previous summer cutting short candidacies from 15 years to 10.

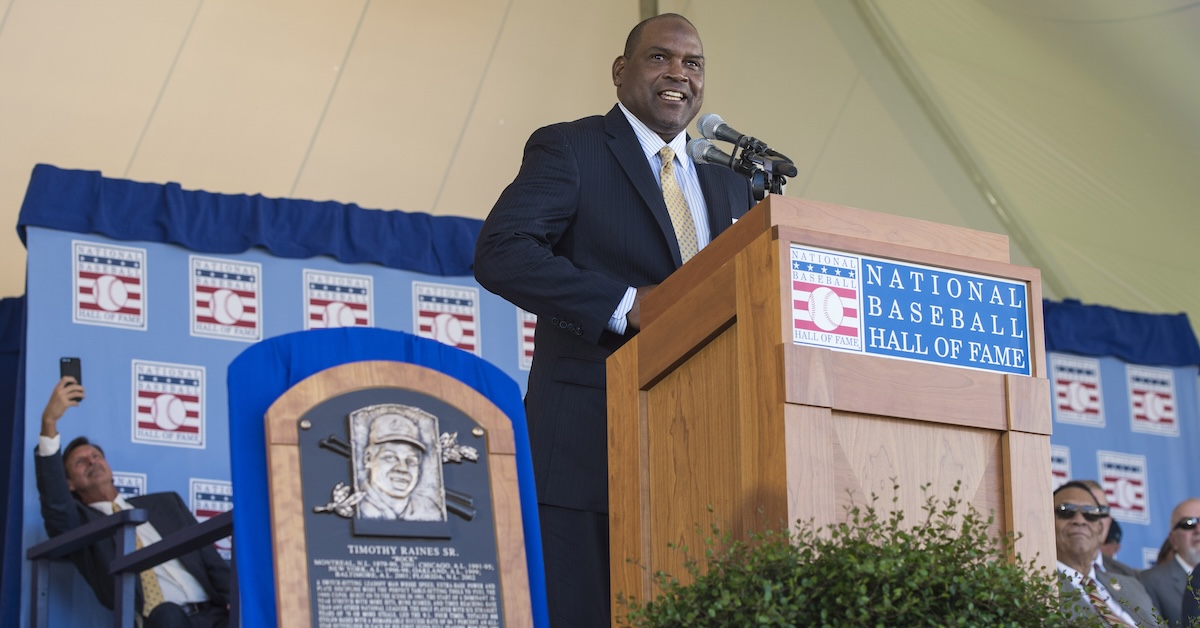

The Casebook, whose publication was delayed by a year because I had so much to say — I went 104 pages over my suggested word count, big surprise — arrived on July 25, 2017, to strong reviews if not robust sales. The elections of some players during the timespan in which I was working on the book, including Piazza and Jeff Bagwell, helped to simplify the editing process. I did allow myself a victory lap by leaving in a chapter devoted to the recently-elected Tim Raines, a favorite player from my youth whose candidacy had started sluggishly before benefiting from the increased attention paid to his career by the stathead community. I wasn’t the only one stumping for Raines, but with some attention paid to the fact that JAWS showed him to be the equal of the much more celebrated Tony Gwynn, his election in his 10th and final year of eligibility was a validation of my work. Likewise for that of Bagwell, elected the same year despite offensive totals suppressed by a shortened career, a good chunk of which was spent in the Astrodome.

Over the next several years, the pattern repeated itself, elevating candidates that at one point or another I hadn’t dared project for election in my annual five-year outlooks — a positive sign, I believe, of the metric’s impact. A stathead favorite would land on the ballot, receive little attention at first — or lose ground amid some of the strongest ballots in modern voting history — but benefit from the repeated exposure of his case and credentials. This certainly wasn’t all my doing singlehandedly, but Edgar Martinez, Larry Walker, and Mike Mussina, all profiled in the Casebook, followed this pattern. Martinez debuted with 36.2% in 2010, sank to 25.2% by ’14, and was elected in ’19, his 10th and final year. Walker, who debuted with 20.3% in 2011 and dipped as low as 10.2% by ’14, was elected in ’20, his final year. Mussina (20.3% in his 2014 debut, elected in ’19) didn’t even need 10 years. Neither did Scott Rolen, who merely got a 200-word capsule in the book; he debuted with 10.2% in 2018 and was elected last year. The likes of Billy Wagner (10.5% in his 2016 debut), Todd Helton (16.5% in his 2019 debut), and Casebook subject Andruw Jones (7.3% in his 2018 debut) are following that path as well. Meanwhile, it’s probably just a coincidence that the player we put on the cover of the Casebook, Mariano Rivera, became the first unanimously-elected candidate in 2019.

Helping to accelerate the rise of these candidates was Ryan Thibodaux’s Ballot Tracker. In the wake of the BBWAA’s choice to publish every voter’s ballot for the annual awards (MVP, Cy Young, Rookie of the Year, Manager of the Year) starting in 2012, voters became increasingly willing to publish their Hall of Fame ballots as well, with nearly 90% voting for a resolution presented at the 2016 Winter Meetings that would require it, only to have the Hall overrule the organization. With the vast majority of voters publishing their ballots on their own accord either via the Tracker or the BBWAA’s own site two weeks post-election, what had always been something of a feedback loop, with voters gravitating towards candidates as they approached 75%, accelerated thanks to the transparency of the Tracker. There was suddenly no need to wait until the next spring for voters to ask their peers whom they cast ballots for and why, then spend the next year mulling that possibility — now they could act on that information more quickly. Oh, we’re going for Martinez these days? I’d better take another look.

The Tracker, social media, and JAWS have combined to turn Hall of Fame voting into a winter spectator sport unto itself, with readers holding voters accountable for their ballots. The results can sometimes interject an element of nastiness or at least uncomfortable scrutiny into the proceedings, but the worst of that happens primarily when voters act as if they don’t owe readers an explanation, or treat their audience with condescension or contempt. Hell hath no fury like that towards a man making a grand gesture of sending in a blank ballot, or one with only one or two candidates checked. As for the Hall of Fame, so long as it can protect those who would prefer to keep their ballots anonymous, the institution loves the free publicity it receives at this time of year.

From 2014–20, BBWAA voters elected 22 candidates over seven cycles, the largest flood of candidates to enter the Hall over any such span. Even with the flood reduced to a trickle lately, with just two candidates elected over the past three years, the highest 10-year running totals of candidates elected have come from the last four cycles (25 from 2011–20, 24 from 2014–23). This happened despite overly qualified players such as Bonds, Clemens, Sosa, Rafael Palmeiro, Manny Ramirez, and Alex Rodriguez failing to get enough support because of their links to PEDs. Particularly with fewer candidates reaching once-automatic milestones like 500 homers and 3,000 hits, and those reaching them sometimes surrounded by suspicion, voters have had to rethink what makes a Hall of Famer, and how to measure it, and for that job, they’ve turned to WAR and JAWS. The honorees haven’t appreciably watered down the Hall, either, despite what some codgers would have you believe. From 2000–11, the writers elected 20 players to the Hall, with an average JAWS of 55.2. From 2012–23, they elected 25 players, with an average JAWS of 58.0. Even after removing relievers from the pool (two in the earlier set, three in the later one), the advantage is 60.2 to 58.4 in favor of the latter group — and again, that’s with some of the best players of the period by WAR and JAWS excluded due to PEDs. While the Era Committee process has still resulted in the election of candidates less favored by the metric (good grief, Harold Baines), the elections of Trammell and Miñoso have added a couple more Casebook-profiled candidates to the plaque room, over by the rest of “my guys.”

JAWS has undergone some minor changes along the way, more than I’ve recounted here. With the help of the invaluable Adam Darowski — himself the creator of the Hall of Stats, a much-respected alternative Hall of Fame metric — at Baseball Reference, I’ve fidgeted with various ways to measure relievers (R-JAWS) and tried to account for lessening starter workloads (S-JAWS). Closer to home, I’m now attempting to incorporate catcher framing data from Baseball Prospectus and FanGraphs. I’ve never built an fWAR version of JAWS — in my 2018 job interview, David Appelman and I agreed that bWAR would remain the official version of the metric even if I was hired — but it’s an idea we’ve mused about.

I don’t want to overstate the impact of JAWS. I’ve never advocated for it as the only criterion by which a candidate should be judged, as it doesn’t account for postseason play, awards (flawed as their voting may be), or historical importance, among other things. And it’s not as though every voter referring to the metric is voting in lockstep with its conclusions. Each one brings to the process their own lifetime of experience and point of view, and there’s plenty of room for disagreement on candidates even beyond the question of how to handle the PED-linked ones. But I hope the metric I created and the body of work that surrounds it have made them more receptive to taking another look when our impressions differ.

I’m genuinely flattered that so many have turned to JAWS in that spirit. I’m grateful to my editors at Baseball Prospectus (Joe Sheehan, Christina Karhl, Steven Goldman, and John Perrotto), Sports Illustrated (Ted Keith and Chris Stone, who put the metric in the magazine a handful of times), and FanGraphs (Meg Rowley, and before her Carson Cistulli as well as Jon Tayler) for indulging me and keeping me on task, and to everyone who’s followed along. I can’t wait to see where JAWS goes in the next 20 years.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/chewing-on-jaws-at-20/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions