Dan Hamilton-USA TODAY Sports

So, so, so much digital ink has already been spilled writing about Shohei Ohtani’s groundbreaking, $700 million contract. It’s a sign of baseball’s new era. Maybe it’s an accounting gimmick. Did he sell himself short? Did he set a new high bar? Is he giving the Dodgers a loan, or an unfair competitive advantage? Is the competitive balance tax broken?

I don’t really think it’s any of those things, as you can probably tell from the fact that I included them in my opening paragraph, and in rapid succession at that. In fact, I don’t have much of an opinion about what this contract “means.” I don’t think it’s a good idea to try to figure out how baseball works based on a unicorn, basically. You’d do just as well trying to figure out how countries work by looking at Singapore, or how weather works by looking at a tornado.

That said, boy do I love numbers, and I especially love goofing around with them. I really enjoyed Jon Becker’s CBT explainer, as well as Rob Mains’s look at deferrals and tax regimes. One thing that I feel very strongly about is that treating this as either Ohtani getting fleeced by the Dodgers or him and the team pulling a fast one on the entire league is misunderstanding the situation.

Here’s how this article is going to go: I’m going to give you a few paragraphs on how I’m thinking about the deferrals in Ohtani’s contract, and then I’m going to give you a new toy. That toy is a spreadsheet that lets you turn any contract with deferred payments into the kind of contract we’re used to, in equivalent terms. Then you can use it to see how things would have gone if Ohtani deferred his money even longer, or if he took more money now, or what a new Juan Soto deal might look like if it comes in this style. Or you can not use it at all! It’s completely up to you.

First things first: acting like the Dodgers were going to give Ohtani $700 million regardless, and that he just let them defer it out of kindness or some desire for them to win now, doesn’t make much sense to me. He’s not a rube who’s never seen a contract. He has a team of people who understand the time value of money, and all that. If the Dodgers gave him a normal deal, they would have offered him less, obviously. Everyone here went into this with eyes wide open.

Here’s the way I like to imagine it. The Dodgers call up Ohtani and tell him they’d like to give him a 10-year deal worth $470 million. Ohtani is sipping a cognac – he’s rich, of course he’s sipping cognac. “That amount works for me,” he says, “but I have some terms. I’d like to invest some of it in risk-free assets over the next 10 years as part of my portfolio-based approach to guaranteeing my children and my children’s children generational wealth. Also, as a very rich person, I’d like to do some tax structuring, so let’s do that too. Why don’t you set the cash aside today, but then put the money into an account for 10 years and invest it in treasuries before paying me?”

Tom Tango pitched it as Ohtani giving the Dodgers a loan. I wouldn’t go quite that far, because they put the money in escrow, but that comes pretty close to the way I see it. If the Dodgers set aside $45 million today and invested it at an annually compounding 4.2% rate (10-year treasuries yield 4.2%, so that isn’t a number I just pulled out of thin air), they’d have $68 million in 10 years. Then they give that $68 million to Ohtani, along with the $2 million they’ve already paid him, to make $70 million. But they’re setting aside $47 million or so in each year of the deal to make the math work, because the current CBA requires teams to set aside “an amount equal to the present value of the total deferred compensation obligation” within two years of when it’s earned. In other words, the Dodgers are setting aside $47 million within the next two years to pay Ohtani for his 2024 contributions, so the deal really does feel like the way I described it, 10 years at $47 million per.

Actually, they’re legally obligated to set aside $46 million, based on the rules of the CBA, which is another confusing part of this discussion. The formulaic competitive balance tax number ($460 million) is often referred to as present value, and it’s certainly a present value, but it’s not exactly the same as the way I’d think about it. Instead of using market rates, it uses a contractually defined rate, the federal mid-term rate reported by the IRS each year. That’s a different thing than the present value you’d get by discounting at risk-free rates ($470 million), but it’s pretty similar, which just makes all of this more confusing. Interest rates are tricky! I wouldn’t quibble with either of those numbers, which is why I prefer to think in “the equivalent value in a normal contract” instead of any of the other options.

The latter method, a risk-free discounting that brings each deferred cashflow back to the year where it’s earned, is my preferred method for evaluating contracts. If you’re getting some money 10 years in the future, but it’s guaranteed, that’s not so different from getting it now and then locking it up in an investment for 10 years. Aside from tax treatment, which probably matters to Ohtani but which I’m going to skip over here because I’m not a tax lawyer, the two are quite similar. To end up with more than $700 million, Ohtani would have to take some investment risk by moving out of treasuries. In terms of a guaranteed amount of money, $2 million today and $68 million in 10 years is equivalent to $47 million today. The real question is how to talk about it, because 10 years and $700 million (but with deferrals!) doesn’t sound a lot like “10 years and $470 million.”

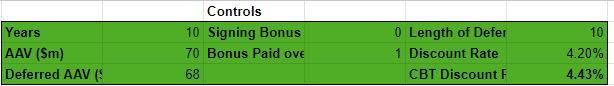

To that end, I made you a spreadsheet. You can take a look at it here. I’ve made it read-only, so that the first reader to start playing around with it doesn’t ruin the fun for everyone else, but you can save your own copy and then do whatever you’d like with it. It’s a pretty straightforward model, but I’ll just walk through the basics. First, there’s the control panel, which looks like this:

This has all the variables you can mess with. Most of them are pretty straightforward: years, average annual value, and deferred average annual value control how long the deal is, how much money is in it, and how much of that money comes right away versus in the future. For the purposes of this spreadsheet, the deals pay the same amount every year, and the deferrals are the same every year, because otherwise there would just be too many variables to fidget with. You can also add a signing bonus, payable over a customizable number of years, if you’d like.

The last column sets up all the math-y parts that you probably don’t want to do. “Length of deferral” is what it sounds like: how many years after each contractual year the player receives his deferred money. Ohtani is getting $68 million for his 2024 play in 2034, $68 million for his 2025 play in 2035, and so on. Each year is deferred 10 years. If you wanted to shorten or lengthen that time, you’d just change that cell. “Discount rate” is a simplified catch-all that handles the time value of money. A fancier model would use a forward curve and interest rates that vary over time, but that’s far more precise than is useful for an exercise like this, and anyway interest rates are extremely flat right now: five-year treasuries yield 4.22%, 10-years yield 4.20%, and 30-years yield 4.31%. Finally, “CBT discount rate” is the contractually determined rate at which payments are discounted for the purposes of calculating the competitive balance tax.

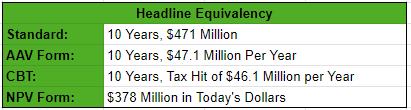

Those are all the inputs you need to define Ohtani’s contract as well as what it’s worth to him and to the league’s bean counters. The next several rows just show the calculations for each year so you can look at them if you’re curious to see it broken down. The meat of the output is at the bottom, what I’ve called “headline equivalency”:

This tells you how to talk about a contract with a given deferral as if it were a regular contract, with all the money paid in annual installments during its term. In other words, after the math is done and assuming my discount rate roughly mirrors Ohtani’s, we could call this contract and a 10-year, $471 million pact equivalent. That’s pretty useful for equating it to, say, Aaron Judge’s nine-year, $360 million deal. It’s more years and more money per year – around $7 million more per year, to be precise. That’s a lot easier to comprehend than “well it’s $30 million more per year, but he doesn’t get most of that money for a very long time, so you have to count it less.”

I also included it in average annual value form, just to save you doing the math. The tax cap hit math just runs Becker’s calculations; it lets you know how much the deal will count against the team’s competitive balance tax payroll. Finally, the last row is money in today’s dollars. We don’t usually think about contracts this way, but clearly the $40 million Judge is getting in 2031 is worth less in today’s money than the $40 million he’s getting next year. This just formalizes that. I don’t think it’s particularly useful because it doesn’t line up with the way we talk about contracts, but hey, it’s there for completeness’s sake.

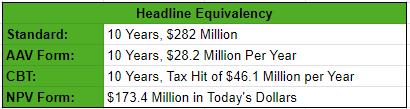

Don’t agree with my discount rate? Change it! Say Ohtani actually thinks that he’s a genius investor who could make 10% annualized returns on the open market. First, I’d say that he probably can’t, and that if he can maybe he should be doing that with his already sizable fortune instead of messing around with salary structures. But hey, you can change the discount rate to 10%, and now you’ll have a new output:

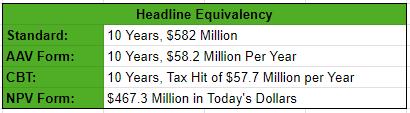

Wow, now he probably should have just taken the money in standard form. That discount rate doesn’t make much sense – risk-free is a reasonable way to think about these things, at least in my opinion – but hey, I built this sheet so you could put whatever you want in, not to tell you what to do. Go nuts. Test out Mookie Betts’s contract, or build theoretical ones of your own. The world is your oyster, so long as you narrowly define the world as consisting of baseball contracts with deferred payments. Here’s another one, just for fun — Ohtani’s deal but with only half the money deferred:

I hope that this tool helps make the point that this isn’t an interest-free loan from Ohtani to the team, or some convoluted workaround, or anything like that. It’s certainly a little weird that Ohtani is only getting $2 million a year in cash, but the rest is just deferred cash, which is also valuable. He’s hardly going to run into cashflow issues; if you gave him an extra $40 million a year, he’d probably just invest it anyway, and besides, he has all that endorsement money to fall back on. Now, you can work out how it would look as a “normal” deal on your own time, and with your own variables. So one more time, here’s the sheet.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/ohtanigraphs-spreadsheet-edition/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions