Bill Streicher-USA TODAY Sports

In the ninth inning of Monday night’s game against the Phillies, Rockies catcher Elias Díaz doubled off Jeff Hoffman with two outs, nobody on, and the game tied 1-1. That put Rockies manager Bud Black in a bit of a pickle. With a runner on second, a single would score the go-ahead run, and Colorado’s best hitter — Nolan Jones — was at the plate. If a single were ever going to come, it would come now.

Rather, a single would score a normal runner from second. Unfortunately, Díaz is slow. He’s in the first percentile for sprint speed. He’s so slow, when he puts a pork shoulder in the crockpot it’s done cooking by the time he comes back from the pantry with the barbecue sauce.

If Black wanted to get that run in from second with a single, he had one of two options. First, call a cab. Second, call for a pinch-runner.

This being the 2024 Rockies, nothing about it was that simple. Black had four reserves on his lineup card: First, backup catcher Jacob Stallings, who’s just as slow as Díaz — literally first-percentile sprint speed as well. Why bother pinch-running? Kris Bryant was not in the lineup after tweaking his back over the weekend, and the other two Rockies reserves, Jake Cave and Brendan Rodgers, were both ill and unavailable to play.

If you’re sick, make sure you wash your hands and cover your mouth when you sneeze, because otherwise Kyle Freeland might end up pinch-running. And believe it or not, it almost worked! Freeland hadn’t run the bases in a competitive game in three years, but he got his money’s worth on this trip. He advanced to third on a wild pitch, and when Hoffman bounced a slider, he saw his chance.

Freeland, wearing Jackie Robinson’s no. 42 on his back, came steaming in for a dramatic play at the plate… only to fail to beat the flip back to Hoffman, who belly-flopped onto his former teammate and applied the tag. Freeland banged his (non-throwing, thank God) shoulder on the play, but he escaped serious injury. The Rockies lost in extra innings.

Was this farcical? Sure. And rare. The last pitcher to score as a pinch runner actually did so a year ago today: Kutter Crawford, who came in as the bonus runner in the 10th inning of a game after the Red Sox had already lost the DH.

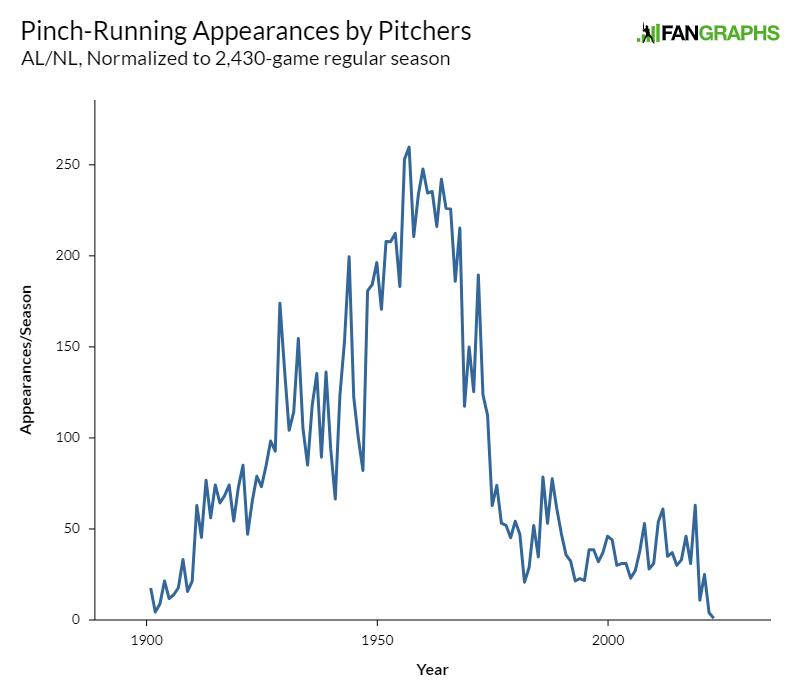

But not too long ago, pitchers pinch-running wouldn’t have had the man-bites-dog newsworthiness they’ve developed in the universal DH era. It was fairly routine, once upon a time.

The universal DH has had a profound effect on pitcher pinch-running appearances. It will surprise no one to learn that Freeland is the only pitcher to pinch-run in 2024; Crawford was the only pitcher to pinch-run in 2023. In 2020 and 2022, there were only four pinch-running appearances per season by pitchers.

Before that, the last season with single-digit pitcher pinch-running appearances was 1909. As recently as 2019, there were 63 pinch-running appearances by pitchers. Freeland’s 180-foot misadventure skews the numbers, because it came only three weeks into the schedule, but as of 2023, pinch-running appearances by pitchers are at an all-time low. (Data from Stathead.)

The situation the Rockies faced on Monday was so extreme it feels like a Socratic thought exercise with an official name — Black’s Paradox, something like that. But I actually think there’s a solid, if somewhat contrarian case for using pitchers as pinch-runners fairly frequently.

Even with the limit on bullpen size, benches are only four players deep as a matter of course, with one of those spots devoted to a backup catcher, who’s usually slower than dial-up internet. Make a defensive substitution here, an early platoon swap there, and all of a sudden you’re scraping the barrel when the ninth inning comes and you need to get a runner home from second.

With 13 pitchers on the roster, you’re telling me not one of them can scoot? That there’s not a single fastball-slider guy in the bullpen who played soccer in high school and can do what the third base coach says?

That seemed to be the case back in the 1950s and 1960s, though times were different then. Pitcher roles were less defined than they are now, with far less concern for players’ physical safety. Also, in an age when your typical ballplayer went through a case of Schlitz and three packs of Lucky Strikes on a game day, exceptional athletes stood out more, regardless of position.

These days, less so. Pitchers now tend to be big, meaty fellows, and with the DH prevalent in college and across all levels of the minors, most of them haven’t run the bases in a game situation since high school. Even a fast pitcher might only have the instinctive baserunning sense of a particularly intelligent hunting dog, and would not be au fait with best practices on how to slide on a close play. This last bit is important, as evidenced by the fact that Freeland almost got maimed while trying to score.

In your typical major league season under current roster rules, more than 800 pitchers will appear in the majors every year, and surely some of them could pinch-run if need be. Michael Lorenzen and Jose Cuas both had seasons with double-digit stolen base totals in college, just to name two, though neither of them would ever be mistaken for Vince Coleman.

Nevertheless, the list of great pinch-running pitchers is heavy on recidivists. In 2021, the last non-universal DH year, no pitcher pinch-ran more than twice. But in 2019, Lorenzen pinch-ran 13 times. Joe Musgrove pinch-ran eight times. Max Fried — multiple Gold Glove winner, so you know he’s a good athlete — did it four times. Two-way college players Brian Johnson and Brendan McKay did it, as did Vince Velasquez, who that year hit a home run and turned a double play out of left field. (Velasquez’s highly effective two-inning stint as an outfielder extrapolates to a hilarious 1,200 runs saved above average per year, according to DRS.) You’ll also find that Black has used this gambit before; he pinch-ran with pitchers three times — including once with Hoffman, ironically enough — in the final three weeks of the 2019 regular season.

The 2019 season was a golden age for pitchers pinch-running; it was the final season of both the 25-man roster and the last non-COVID season before the size of a pitching staff was restricted. That meant benches were shorter than ever, and managers had to get creative.

Over the past 10 full seasons, the manager who called for a pitcher to pinch-run the most times in a single season was David Bell of the 2019 Reds, who did it 17 times. That was conditioned by the presence of Lorenzen in Bell’s bullpen, though Sonny Gray and Tyler Mahle both ran off the bench more than once. That’s the norm, though. Only five teams in the past 10 full seasons have employed a pitcher as a pinch-runner more than 10 times.

In short, a manager doesn’t go out of his way to have a pitcher pinch-run; normally, he’s just taking advantage of marginal flexibility afforded by knowing he has a fast pitcher on his roster. But when such a player is available, some managers get more excited than others to use him.

Most PR Appearances by a Pitcher in a Season, 1995- Present

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

A lot of the top guys on this list are either former two-way players or had a reputation for being athletic. Hampton and Leake especially — we Mikes are a sprightly bunch.

But wait a minute: Estes in 1999 and Leake in 2011 had the same manager. A little off the scale, there’s Edwin Jackson with six pinch-running appearances for the 2017 Nats, Bronson Arroyo with five for the 2008 Reds, Estes again with four each for the Giants in 1996 and 1997. You can surely see the glasses and toothpick by now: Dusty Baker, I presume?

Since we’re fully into the realm of trivia rather than research, let’s zoom the historical lens out one more time. Even Baker’s greatest detractors (or advocates, depending on what normative stance you take) would never accuse him of being as great a meddler as the famous managers of days gone by.

Let’s entertain a scenario in which a rookie pitcher named Ruben Gomez pitched well enough to get a couple token downballot MVP votes for his 204 innings of work. But that he’d been used even more as a pinch-runner — 32 appearances to 29 — than as a pitcher. Who would you guess his manager was?

Most PR Appearances by a Pitcher in a Season, 1901-Present

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

Very good; Leo Durocher was indeed the correct answer.

Though Dick Williams deserves an honorable mention. Williams famously quit after Year Two of Oakland’s championship three-peat in 1973. The official reason was a falling out with A’s owner Charlie O. Finley. (After his resignation, Williams attempted to sign on with an owner who was easier to work with: George Steinbrenner of the Yankees.)

What if Williams ruined his relationship with Finley because he insisted on using Blue Moon Odom as a pinch-runner? Odom pinch-ran 28 times in 1972 and 20 more times in 1973. For his career, Odom pinch-ran 105 times, which is the second-highest total for a pitcher in the modern era (since 1901, AL and NL only), behind only Pedro Ramos’s total of 120. Odom has also scored the most runs as a pinch-running pitcher, 31, and stole the most bases, four. (Stathead says this honor belongs to Anthony Gose, but that’s a fluke of the search system. Gose’s five stolen bases as a pinch-runner all came during his early career as an outfielder; the future left-handed reliever stole 70 or more bases in a minor league season twice before converting to the mound.)

Herb Washington might not have been able to hit or play the field, but at least he wasn’t a pitcher, Finley must’ve thought.

I don’t believe that evolution — at least in baseball — is either inexorable or unidirectional. Even having pitchers pinch-run is about as rare now as it was 115 years ago, despite a spike in the middle of the last century. What better evidence could you ask for that the genie can be put back in the bottle?

But the better the empirical understanding of the sport, the greater the tendency toward optimization, and eventually, sameness. Even a tactically homogeneous sport can be regulated into an entertaining product, and this I’d argue MLB has done quite effectively in the past five years. The rare pitcher pinch-running appearance — even this one was silly both in conception and outcome — is a curio from a time long gone. We should embrace new sillinesses as they emerge, because they too will one day be obsolete.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/when-throwers-have-to-run/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions