The author with his first black bear of 2022. Tyler Freel

When it comes to game animals, bears possess an aura unlike any others—especially when it comes to toughness. They are often talked about as if they are supernatural specters of the woods, far more difficult to kill than a deer. Their phantom-like qualities (both real and exaggerated) stoke deep-rooted opinions about killing them efficiently with a bow and arrow. These opinions seem to be especially prevalent among folks who have never done it before. Making good archery shots on bears is simple, but it is a little different than shooting ungulates like deer.

Distilling the Lore

Even experienced bear hunters will give you differing opinions about what rifle cartridges or broadheads you need to use, shot placement, and blood trailing.

If there’s any universal advice to heed when it comes to making clean, ethical shots on bears, it’s to take all that “advice” with a grain of salt and understand the context in which it’s given. Bears are incredibly tough and tenacious, and should always be taken with great care, but they are technically very easy to kill cleanly and quickly. Pretty much every tale of woe I’ve heard about hard-to-kill bears begins with a poor first shot. Screw up, and all bets are off. But if you put a sharp broadhead through both lungs, the bear (no matter how big he is) will be dead—usually very quickly.

Visualizing the Vitals on Bears

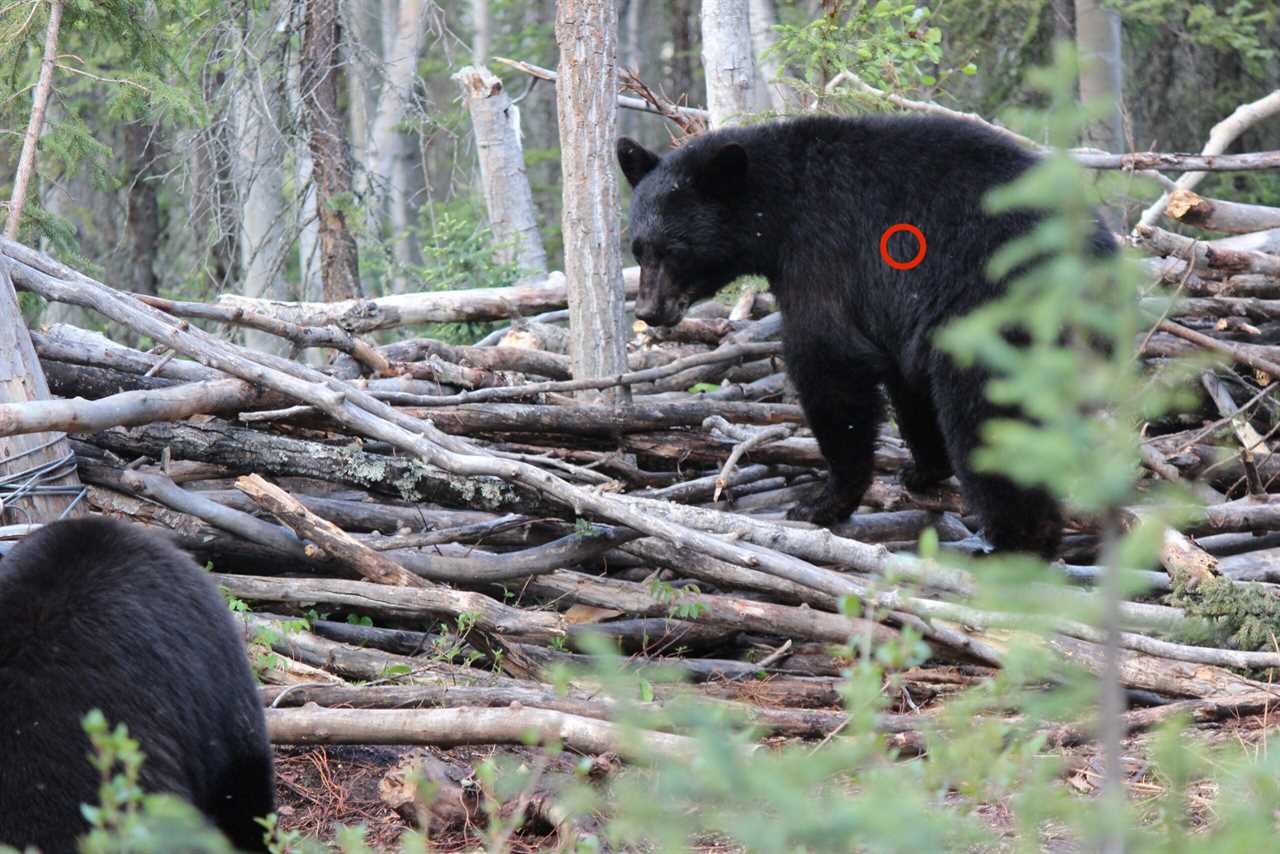

As with any game animal, shot placement is critical for bears. A bear’s anatomy is relatively straightforward. The heart and lungs sit a little farther back compared to a deer. Many hunters are often told to place their shot in the “middle of the middle.” This means halfway between the back of the shoulder and front of the hips, and halfway between the top of the back and bottom of the belly. When standing perfectly broadside, this is generally good advice, and your shot will go through the large rear portion of both lungs. However, I typically tend to favor just slightly forward of middle.

I’d recommend holding for a double-lung shot rather than intentionally aiming for the heart. Heart shots are great, but I’ve found that a solid double-lung shot seems to kill bears more quickly than a heart shot. Often, double-lunged bears won’t death moan, but you can usually hear sounds of air coming through the wound.

The issue with a simple mantra like “middle of the middle,” is that bears will often present a variety of good shot angles, but with each angle, the optimal aiming point changes. For example, a bear that is quartering away at 45 degrees offers a devastatingly effective shot angle, but that’s only if you aim farther back. If you hold for the same spot you would on a broadside bear, you may not even kill the bear with this shot angle.

One of the most common shot-placement mistakes I’ve seen is aiming too far forward (I’ve done this myself). Sometimes a shot entry that would be perfect on a deer won’t even get into the chest cavity on a bear.

In fact, I shot a nice black bear boar the other night. I hit him six or eight inches behind the front shoulder, and he expired in about 15 seconds. When skinning him, I found a recent broadhead wound, through the front shoulder and out through the brisket. The bear behaved as if nothing was wrong. I’ve seen several bears over the years hit forward or just low in the armpit—which would mean a heart shot on a deer—and it doesn’t even kill them. There will be a heavy bloodtrail for a few hundred yards that then dissipates into nothing.

When a bear is quartering away, you want to aim farther back. This aiming point would produce a deadly double-lung shot. Tyler Freel

The biggest key to aiming at the right place on bears is to understand where their vitals sit and visualize them at any given shot angle—and clearly pay attention of the bear. I’ve made a few marginal shots over the years because the bear was at a slightly different angle than it seemed in the moment.

For as straightforward as understanding black bear anatomy should be, even many of the bowhunter education diagrams get it wrong. In the popular projector-slide overlay diagrams that IBEP uses, the vitals of the bear are shown slightly farther forward than they are in real life. One of the most accurate references that I’ve found is a widely-shared photo attributed to Woody Sanford of a necropsied black bear that’s frozen and stood up to show where the vitals sit. This image has been posted on various forums and websites for nearly 20 years. Although its front leg is slightly back, it gives a good picture of where the heart and lungs sit. While broadside with both legs straight, aim just slightly forward-of-center (halfway between the front of the hind legs and back of the shoulder) and halfway up from the bottom of the belly fur and you’ll center punch both lungs. If the bear has its front leg forward and you try to tuck it low just behind that shoulder, you’re likely to miss everything vital.

With the front leg held this far back, you want to hold close to it. Tyler Freel

This guide published by the Alaska Dept of Fish and Game gives a pretty accurate representation of a bear’s anatomy. With the front leg back, you’d want to aim just behind it, but if the bear were standing flat-footed and broadside, the biggest portion of the vitals would be back farther from the shoulder.

Especially in low-light conditions, bears can be a little more difficult to aim at compared to deer because their thick fur can hide definition in their bodies. This makes it harder to find an exact “spot” to aim at. For a compound with bright pins, it isn’t as much of an issue, but if you’re shooting a traditional bow with an instinctive aim, it requires a bit more attention and focus.

This points sound like basic bowhunter-ed information, but the knowledge is good-as-gold. Put your arrow through both lungs, and you’ve got yourself a bear every time.

When a bear is broadside and front leg is forward, aim almost halfway back from the front shoulder to the hips. If you shoot tight to the front shoulder, you risk losing the bear. Tyler Freel

The Mental Game of Making a Good Shot on Bears

Most hunters are familiar with the term “buck fever,” and probably have experienced it at some point. Well, it certainly exists with bears—and can be even worse. Bears often invoke a surge of adrenaline like no other animal. I’ve been fortunate to kill many black bears over the years, but my heart still starts pounding when one appears out of the woods. It’s one of the things that draws me to bear hunting, but it can also be a huge obstacle for accurate shooting.

The bear shakes have gotten the best of many hunters. Many shots have been flubbed, and sometimes a hunter can’t even draw their bow. I’ve seen videos of hunters become emotional wrecks in the presence of a bear, sometimes shaking uncontrollably.

This video is a great example of nerves on the first shot producing a clean miss, then a perfectly-placed second shot.

If you’re a first-time bear hunter, don’t let this scare you. Just be aware that you will need to have a plan for controlling your motor functions during that surge of adrenaline. I find that deep, slow breathing helps. Patience is also key. Usually, I don’t have to be in a rush to push a shot at the first opportunity.

Have a specific process that you follow when executing each shot and focus on that process, not the bear’s presence. Your brain will be wanting to get rid of the arrow as quickly as possible, and sometimes simply getting your sight picture onto the bear will cause you to punch the trigger or let go of the string. This usually means poor results. If you develop a specific shot process and follow it when a bear is in front of you, you will shoot more accurately.

Recovering Your Bear

Bears have a reputation for being tough to recover for several reasons. Their blood trails tend to be miniscule, they tend to lay very flat to the ground, and without antlers or hooves, they can move through the underbrush more-quietly than most ungulates.

Bears tend to leave significantly less-substantial blood trails than ungulates, mostly because of their physiology. Some bear hunters will tell you it’s their thick hair that absorbs the blood, or fat that clogs the wound. I’ve noticed that the subcutaneous tissues often move around and cover up the wound beneath the skin. Even when skinning, a big broadhead cut generally doesn’t create a gaping hole, and you have to dig around to find it.

The most important thing you can do after shooting a bear is simple: Take careful note of where your shot impacted and the angle. Resist the urge to do anything other than watch and listen. If it’s quiet and you’ve made a good double-lung shot, the bear will usually be lying dead in the last place you heard him. Sometimes you’ll be able to see their last movements before they lose their feet.

I never count on being able to find blood. Last year I shot three black bears, and only one left any blood trail at all. Using a wide-cutting, scary-sharp broadhead does often improve blood trails, but even with a 3-blade broadhead and an exit, you might not get anything. I was able to quickly find all three bears based on where I last saw and heard them. I personally prefer cut-on-contact, single-bevel broadheads like the RMS Gear Cutthroat, and their 3-blade Cutthroat works well too. Other great options are the Iron Will wide-cut broadheads, and even Magnus Stingers or well-sharpened Zwickeys work great. Good-quality expandable broadheads work great most of the time as well, just make sure to shoot the bear in the ribs.

Bears can be particularly difficult to find—even when you’re right on top of them. If there’s thick underbrush or even tall grass in uneven terrain, they can practically disappear. When they die, bears tend to conform to the ground, and if they fall in a depression, you may have to walk right on top of them to find them. Keep this in mind and trust your gut and observations. If you made a good shot and a good estimate of where you last heard the bear, take your time and be thorough. If you heard a death moan, keep in mind that they often sound farther away than they really are.

Read Next: Growing Black Bear Populations Could Mean a Bear Hunting Boom in America

There’s no set time-limit for waiting to look for your bear, and if I hear lung sounds or a death moan, I’ll usually go find them within 15 or 20 minutes of the shot. If your shot is less-than-ideal or you’re unsure, you may need to either wait or pursue them immediately. For questionable shots that are back further—think liver or guts—you need to wait. The bear usually won’t go far before bedding down, but will take time to expire. I’ve encountered a couple over the years that I bumped up and were still alive a few hours after being shot. Waiting overnight, if possible is usually a good call. However, if you hit a bear too far forward, or in the spine, your only chance of recovery is usually to pursue them immediately and either run them up a tree or get another shot.

Bears present their own unique challenges for archery hunters, but objectively, they are relatively easy for a bowhunter with good equipment to kill quickly and ethically. From all the bears I’ve seen, double-lung archery shot bears seem to expire even more quickly than rifle-shot bears. So keep your nerve, pay close attention to the angles, and shoot well.

The post Keys to Making Good Archery Shots on Bears (and Recovering Them Quickly) appeared first on Outdoor Life.

By: Tyler Freel

Title: Keys to Making Good Archery Shots on Bears (and Recovering Them Quickly)

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/keys-to-making-a-good-archery-shot-on-bears/

Published Date: Tue, 24 May 2022 13:32:32 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions