Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports

Earlier this week, I wrote about Emmanuel Clase. Specifically, I wondered whether a lower release point, or whatever caused that lower release point, was the reason his performance took a step back in 2023. I don’t know the answer for sure. I don’t even think there is a way to know the answer for sure, but I’ve spent the last few days thinking about release points. Clase’s has fallen roughly two inches over the last two years. That feels like a lot to me, but I realize that I don’t have a basis for that feeling. What happens to a pitcher’s release point on a year-over-year basis? Does it stay the same? What constitutes a normal amount of variance? Does it only fall off once things are starting to go wrong? Does it slowly degrade over time just like the pitcher himself, who is after all merely an ephemeral vessel of bone and sinew, destined to return unto the dust?

Naturally, there’s only one place to find answers for metaphysical questions like these: Baseball Savant. I pulled the average vertical release point for every pitcher in the Statcast era, calculating the year-over-year change for their primary fastball. For pitchers who threw both a four-seamer and a sinker, I ignored whichever pitch they threw less often. I also threw out seasons in which players changed their release point by more than four inches, which to me indicates an intentional change to a pitcher’s delivery and overall approach to pitching. We’re interested in cases like Clase’s, where his release point changed unintentionally as he tried to pitch in the same way.

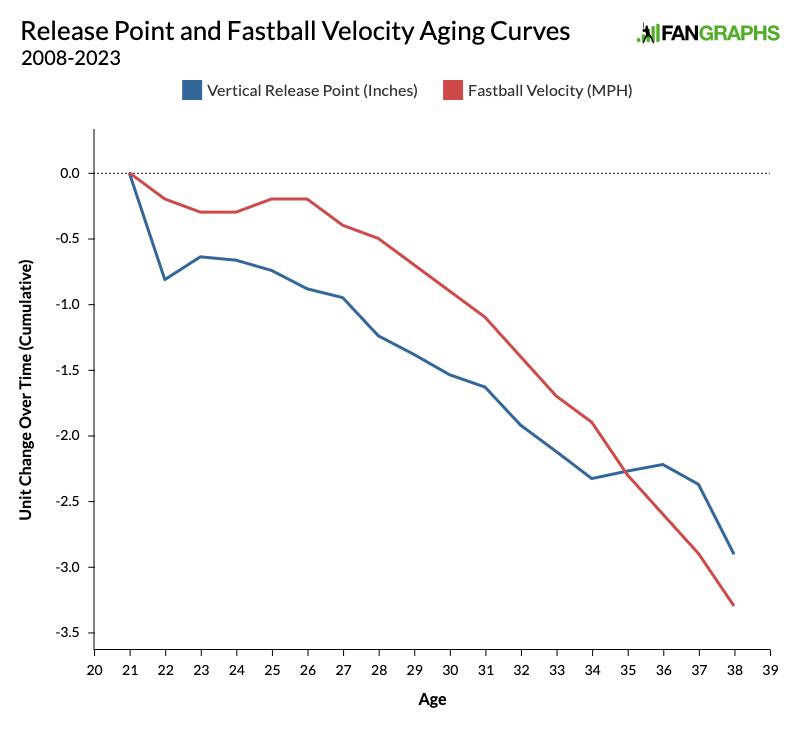

That left me with a goodly sample of 5,353 player seasons. In addition to calculating the change in vertical release point, I also noted the change in fastball velocity, along with the changes in the pitcher’s overall FIP-, whiff rate, and groundball rate (adjusted to league average). The first thing I did was create an aging curve, but before I show it to you, I’d like to tell you what I was expecting to see.

Going in, my hunch was that release point would fall gradually over time. Not only that, but I expected that few players would see their release point tick up from one year to the next. This hypothesis was partly informed by my own personal experiences as an (extremely) amateur pitcher, but it also seemed like common sense.

Per Joshua H. Lam and Bruno Bordoni, “The primary muscles involved in the action of arm abduction include the supraspinatus, deltoid, trapezius, and serratus anterior.” You might recall that Wade Miley is dealing with a strained posterior serratus right now and that Andrés Muñoz hit the IL with a deltoid strain back in April. While there wasn’t a documented trapezius injury in 2023, pitchers Lance Lynn, Kyle Zimmer, and Justin Anderson all suffered trapezius strains over the last few years. The supraspinatus is a part of the rotator cuff, and the list of pitchers who have suffered rotator cuff injuries is long indeed. In other words, pitching is known to create wear and tear on every single one of the primary muscles involved in raising the arm. It makes sense that it might affect one’s ability to do so, even for those lucky enough to avoid major injury. And that’s before accounting for the normal effects of aging, such as decreased flexibility. With that, here’s our aging curve:

That is very definitive. Release point tends to fall over time. Even if you don’t trust the edges of the graph, the average pitcher’s release point drops by more than 1.5 inches between the ages of 24 and 34. As with any aging curve, it’s important to keep in mind that there’s some serious survivorship bias going on here. Pitchers whose release point fell from one year to the next generally threw slightly fewer pitches in the second year, somewhat minimizing their impact on the curve.

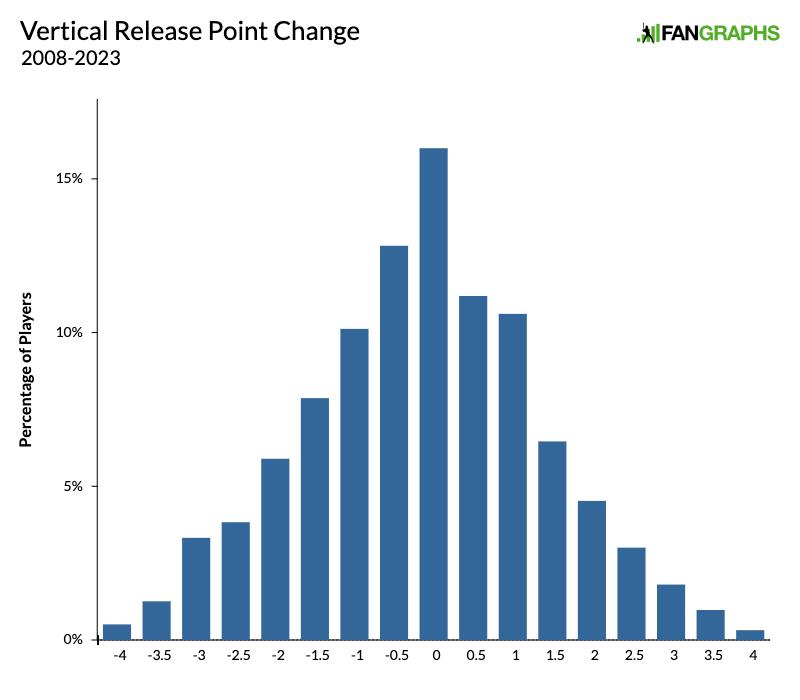

Maybe the most interesting part of all this data is the distribution. The average pitcher’s release point falls by just 0.13 inches per season, and the standard deviation is a surprisingly large 1.5 inches. Here’s what that looks like in graph form, putting all year-over-year changes into buckets of 0.5 inches:

In a given year, 51.6% of pitchers see their release point drop, while 45.2% see a gain. While the overall trend is down, it really is very slight, and a pitcher is nearly as likely to raise their release point as they are to lower it. A year-over-year drop of an inch, like Emmanuel Clase’s, is in something like the 73rd percentile. It’s a large drop, but by no means enormous (though when it happens for two consecutive years, it’s definitely a little more worrisome).

The last thing I did was run some correlation coefficients, using fastball velocity as something like a control variable:

Vertical Release Point and Performance Correlations

| Factor |

Vert RP |

FB Velo |

FIP- |

Whiff% |

GB%+ |

| Vert RP |

– |

-.01 |

-.01 |

.01 |

-.05 |

| FB Velo |

-.01 |

– |

-.29 |

.29 |

.13 |

An increase in fastball velocity is correlated with a better FIP, more whiffs, and more groundballs, just as you’d expect. Even after accounting for the survivorship bias that I mentioned earlier, I was a surprised to find essentially no correlations between vertical release point and, well, much of anything (though because release point falls at roughly the same rate as velocity, the correlation between the two might be understated). Still, I assumed that injury is at least one of the reasons a pitcher’s release point might fall. As such, I expected a lower release point to be correlated with some drop-off in performance. Instead, the only correlation for which you could make any real argument is groundball rate, presumably because a lower release point means a shallower vertical approach angle. I think there’s a lot of room for more study, but so far as I can parse it, this data is telling us that even a drop on the order of an inch or two isn’t necessarily a warning sign that a pitcher’s performance is about to fall off.

Many thanks to Dr. Paul Canavan, who took the time to introduce me to some of the research on the biomechanical reasons that older players might have lower release points.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/fallen-angles-a-lower-release-point-isnt-necessarily-a-sign-of-impending-doom/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions