Jovanny Hernandez/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

With the news that Byron Buxton is eyeing up a return to center field, the Minnesota Twins have quite a bit of flexibility at the heavy end of the defensive spectrum. When they need some thump and don’t care much about the defensive consequences, the Twins can choose from a variety of designated hitters, left fielders, and first basemen: Matt Wallner, Alex Kirilloff, Trevor Larnach, and most recently Carlos Santana.

Santana, who will turn 38 just after Opening Day, has been around so long he’s the only reason anyone remembers Casey Blake. By now, you know what he’ll provide: Lots of walks, a little power, and decent defense at first base. Santana’s last season of 2.0 WAR or more was 2019, and after spending 10 of his first 11 seasons in Cleveland, he’s bounced around quite a bit; this is his fifth team since the start of the 2022 season.

In other words, he’s a second-division starter at first base or DH, which is an archetype of player we’ve had pegged since time immemorial. And not to put too fine a point on it: A veteran DH who hits five Central Division teams in a five-season span is kind of like a rock band extending its career by playing the state fair circuit. You still want to see REO Speedwagon, but maybe not as much as you did in 1981.

Surely the Twins know that, and for one year at $5.25 million, they don’t even need Santana to play every day in order to come out ahead on this investment. Like the Blue Jays and Justin Turner, they’re hoping to get one last productive season out of a guy who was a really good hitter for the previous decade, while running the risk that this is the year his bat finally gives up and goes to live on that farm upstate.

There are three reasons the Twins were able to get Santana for less than half what Toronto paid for Turner. First, Turner can… well, I think “play second base” is probably stronger phrasing than I’d like to use. But he can stand there with a glove without getting the bends. Second, Turner was a better hitter than Santana last year — really, for the past five years — and the signs of his decline are less pronounced than Santana’s. Third, while Santana still has excellent strike zone judgment, his walk rate in 2023 was the lowest of his career by some distance, and his power and quality of contact numbers have been on the decline basically since the pandemic, a brief renaissance in 2022 notwithstanding.

Santana can still be a useful offensive contributor, perhaps even an above-average hitter overall, if he gets his walk rate back up into the 14% range, instead of hovering around 10%. But whether he does so is less interesting to me than what he represents for the future of first base and DH overall.

His whole career, Santana has been an on-base machine despite putting up pedestrian numbers as a hitter specifically. In 2019, he hit .281/.397/.515; that’s the only season in which he posted a .270 batting average or a .500 slugging percentage. He only has one other full season each of hitting .260 or slugging .460. But even with half a decade’s worth of decline phase rate stats on his ledger, Santana still has about the same career OBP (.356) as Xander Bogaerts and about the same career wRC+ (116) as Ian Happ.

That’s because his career walk rate, 14.8%, is the same as Mike Trout’s. They’re tied for fifth among active hitters, just a fraction behind Max Muncy and Bryce Harper.

Maybe this is a bit of the Baader-Meinhof effect. Joe Mauer — another Twin, a former catcher-turned-first baseman with an OBP-over-power offensive profile — just got elected to the Hall of Fame. (Because all news is local, I’ll mention that according to Wikipedia, the phrase “Baader-Meinhof phenomenon” first appeared in a 1994 letter to the St. Paul Pioneer-Press. Once you’re aware of the Twin Cities, you see them everywhere.) And personally, I was just mulling over a choice of first basemen in my Diamond Mind league draft: Nolan Schanuel, Ryan Noda, or LaMonte Wade Jr.

What do these players have in common? OBP over power, at a position that — until recently — tended to prioritize the latter.

Last season, seven players posted an OBP of at least .340 with a SLG under .440 while taking 400 or more plate appearances and playing at least 60% of their games at first base or DH. In the Wild Card era, 2010 is the only season with more players meeting those criteria.

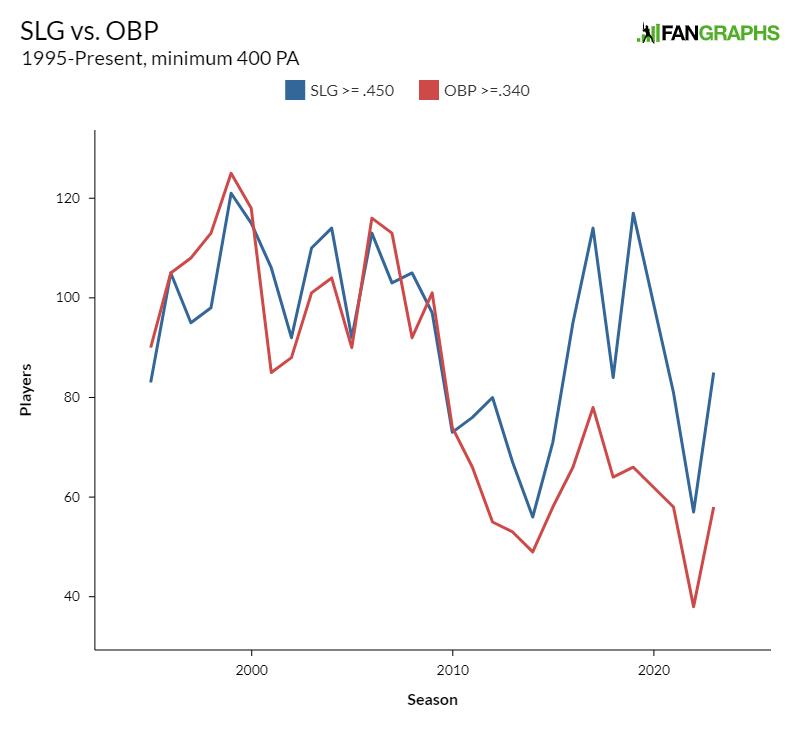

There’s nothing particularly compelling about those specific arbitrary cutoffs, or even the slightly different set I’m about to throw at you. Only that they illustrate a point that’s going to jump out once you see the following graph. This is the number of players at any position, per year of the Wild Card era, who had an OBP of .340 or better and a SLG of .450 or better in at least 400 PA:

From 1995 until about 2010, the run-scoring environment went up and down year-to-year, but in the 2010s, the two qualities diverged. Power numbers returned to the peaks of the steroid era, particularly during the juiced ball period of the late 2010s, while league-wide OBP plummeted amid skyrocketing strikeout rates. The nadir came in the early 2020s, which led to the crackdown in sticky stuff, the pitch clock, and new fielder positioning rules. And sure enough, offense rebounded in 2023.

Rather than track individual seasons at arbitrary endpoints, let’s look at league-wide numbers. Batting average makes up a fraction — usually more than half — of both OBP and SLG. The first part of both getting on base and accumulating total bases is registering base hits. ISO, um, isolates how good a hitter is at accumulating total bases beyond singles, while an equivalent stat for OBP would do the same for walks, hit-by-pitch, and the other means of reaching first base. We don’t really need one, because OBP and average use different denominators, which would make the math a little hairy. And walks make up almost all of the OBP-to-batting average gap such that walk rate alone is a useful proxy.

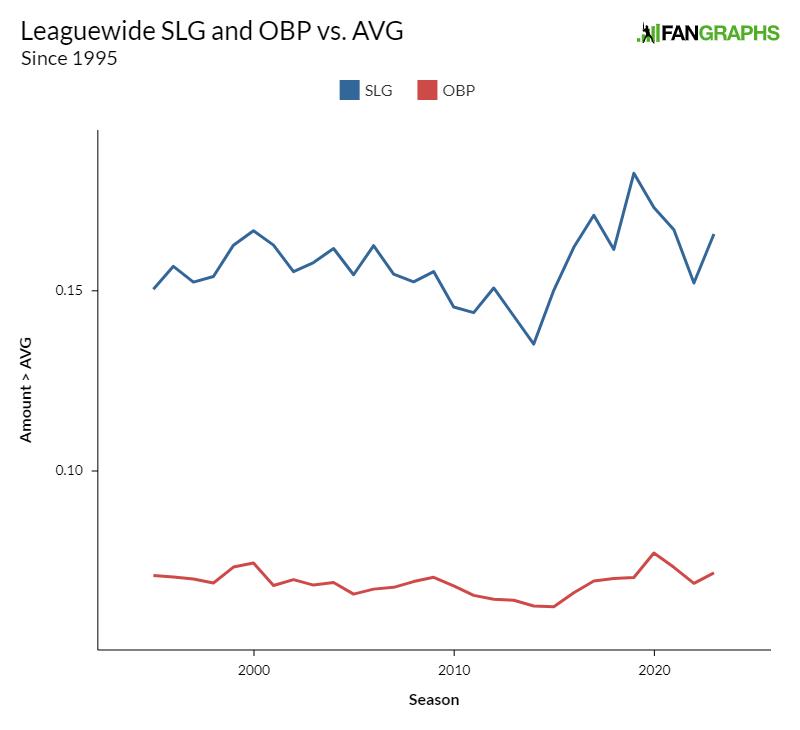

Nevertheless, let’s look at the league-wide ISO, and how much it fluctuates when compared to the difference between the league-wide OBP and the league-wide batting average:

Again, there’s a big spike in ISO in the late 2010s. Power in general is more volatile than OBP; since 1995, the league-wide ISO has been as high as .183 (in 2019) or as low as .135 (in 2014), a difference of 48 points, or 36%. If you take out 2020, when everything was a bit out of whack, the difference between league-wide OBP and batting average has only varied by 12 points, or 20%.

Five years ago, power was extremely cheap and plentiful; on-base ability was not. So where a few years ago the league’s DH and first base positions were populated with relatively low-OBP, high-SLG players, because they were a dime a dozen, we’re seeing a shift toward high-OBP, comparatively low-SLG hitters in those positions now as it becomes easier to get on base but harder to hit home runs.

I don’t know if the sudden proliferation of Santana-type hitters on the left end of the defensive spectrum is anything more than a coincidence. As fascinating a player as Noda is, I’m not sure the A’s have any special interest in him other than the fact that he owns a first baseman’s mitt and makes the league minimum. But we might be seeing a shift toward OBP over power in these major offensive positions.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/first-basemen-need-to-change-their-evil-ways-baby/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions