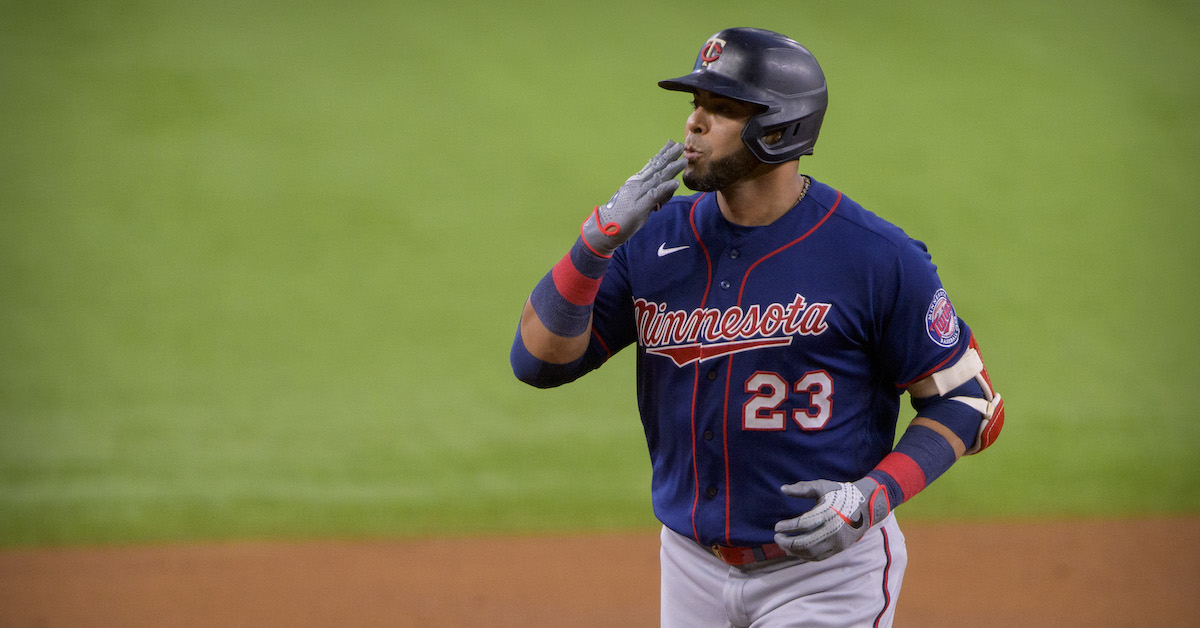

Jerome Miron-USA TODAY Sports

As the professional baseball career of Nelson Cruz flashes before my eyes, no single image emerges to define his legacy. He served as a leader in the clubhouse, was devoted to off-the-field humanitarian efforts, proudly represented his Dominican homeland, consistently hit the baseball so hard that he earned the nickname Boomstick, and did all of it at a high level for more years than any aging curve would have dared to predict.

Last week, after 19 seasons in majors, Cruz announced his retirement on The Adam Jones Podcast. He also addressed the second-most important topic pertaining to his career: the origin of his nickname. Back in 2009, while playing as himself in a video game for some sort of promo event, Cruz hit a home run and referred to his bat as the Boomstick. The name circulated amongst fans and stuck.

Though the name is a straightforward reference to Cruz’s ability to inflict the kind of damage to a baseball that can be heard for miles around, the moniker, like him, owns a larger legacy. In 2012, while Cruz was in Texas, the Rangers introduced the Boomstick hot dog, a two-foot, two-pound contrivance smothered in chili, nacho cheese, and onions. After playing eight seasons with Rangers, he left following the 2013 season, but despite that, the Boomstick remained on offer in Arlington, even after the team moved to a new stadium in 2020. Not only does the Boomstick display admirable staying power for a novelty menu item, but in 2023, the Rangers also doubled down, introducing a burger version of the Boomstick, upgraded with crispy onion rings and a brioche bun.

Through the (hot dog) Boomstick’s tenure, it satiated fans as they endured a World Series famine. The season before its debut, the Rangers famously came within a single strike of winning it all, but calamity struck when David Freese sent a fly ball to right field that Cruz badly misplayed, allowing the tying run to score.

In the twelve intervening years, the team could have distanced itself from Cruz, pulled the item from the menu, not brought it over to a new stadium, and attempted to excise whatever demons haunted the franchise from the 2011 title run. But Texas didn’t. Cruz himself could have let that play become the avatar for his career — let it hang around in the back of his mind and let the guilt and self-doubt stifle his abilities for whatever remained of his career. But he didn’t.

In his podcast interview, Jones refers to Cruz as “the gente,” or a big brother figure in the clubhouse, and asks him how he developed his calming leadership style. He responds with a story about Michael Young, the veteran third baseman who guided him during his early years with Texas. After a game where Cruz left the tying run on second in the ninth inning, with Mariano Rivera taking him down on just three pitches, Young provided a pep talk: “It’s not gonna be the first time, it’s not gonna be the last time, so move on.”

Cruz moved on from his postseason blunder in 2011. He also moved past a PED suspension in 2013. At that point in time, players associated with PEDs quickly went from heroes to villains, their reputations taking on irreparable damage. Ryan Braun, Alex Rodriguez, and Melky Cabrera never redeemed themselves in the eyes of fans. Cruz, though, owned up to his mistake and found a way forward. He issued a statement explaining his actions and taking responsibility for their consequences, then followed his words with actions. Over the next ten years and six organizations, he volunteered his time to work with younger players, both in the big leagues and the minors, to advise them against using PEDs.

Importantly, Cruz’s voice carries weight. Managers, executives, and teammates all gushed about his leadership. Twins manager Rocco Baldelli once referred to him as “one of the best human beings you’ll ever be around” and went on to praise his clubhouse presence, describing him as “a guy you can rely on to set a good tone in that room, to take care of things in that room, to show people a model of how to be a true professional at this level.” Twins GM Thad Levine called Cruz’s demeanor “effervescent.” Trevor May was quoted saying, “Everyone notices that he works his butt off and that bleeds over.”

That clubhouse energy led to a heavy recruiting period every time Cruz hit free agency late in his career. Jonathan Schoop texted him several times a week in an effort to entice him to the Twins; that same offseason, he fielded calls from Alex Bregman selling him hard on signing with the Astros. Later on, fellow Dominicans Juan Soto and Manny Machado led campaigns to bring him to the Nationals and Padres, respectively.

Cruz commands a palpable presence, and he wields it with intent. Prior to spring training in 2019, he sought out insight from Twins personnel on the team’s young players, asked to have his locker put next to then–25-year-old Miguel Sanó, and always made himself available to answer questions and give advice.

His relationship with Dominican players such as Soto, Sanó, and Machado is part of the strong connection Cruz maintains with his home country. He played in parts of nine LIDOM seasons between 2001 and ’23, making a special point this year to play in each of the Dominican Winter League’s five stadiums before officially retiring from winter ball. He also played for the Dominican Republic’s national team in four iterations of the World Baseball Classic, helping them win it all in 2013 and serving as a player-general manager for the team this past spring. When speaking to the importance of representing his country and its passion for baseball, Cruz distilled it down to two numbers: “I played for [eight] MLB teams, but I can only play for one country.”

But for Cruz, love of country meant more than just donning a uniform. Boomstick23, his charitable foundation, works to provide educational and athletic opportunities to children in underserved communities in the Dominican Republic, as well as working to provide running water, electricity, and emergency medical services to Las Matas de Santa Cruz, a small town near the Haitian border where he grew up. That earned him recognition at the 2020 ESPYs, where he took home the Muhammad Ali Sports Humanitarian Award. “All the work that you do, you don’t do it expecting to be recognized,” he said that night. “I never did it to be recognized. I just thought it was the right thing to do.” He followed that up by winning the Marvin Miller Man of the Year Award a few months later, as well as the Roberto Clemente Award in 2021.

Cruz’s ability to lead and care for people on and off the field made him something of an unofficial player-coach. As Twins president of baseball operations Derek Falvey saw it, “He was just a partner. It kind of felt like he was part of the staff in many ways. And at 7 o’clock (each day), he went to go hit. It was just awesome.” It was that devotion to hitting that kept Cruz in the league for 19 seasons, earning him seven All-Star appearances, four Silver Sluggers, and five top-ten finishes in MVP voting. He rides off into the sunset with a career .274/.343/.513 slash line, a 128 wRC+, 40.7 WAR, 2,055 games played, 2,053 hits, and 464 homers. Consider, too, that two of his top-ten MVP finishes came in his age-38 and age-39 seasons; 307 of those home runs came in his age-33 season or later; and his wRC+ didn’t dip below 123 until his age-41 season (during which it was later revealed he needed eye surgery).

Most will remember Cruz for his myriad of positive contributions in and around the game of baseball, but analytical researchers will remember him as the guy who made an absolute mockery of the aging curve. Aging curves differ slightly in methodology and likewise in results, but in general, most estimate that hitting abilities hover around their peak between the ages of 26–31, then start a gradual decline that steepens the older a hitter gets. According to wRC+, Cruz legitimately hit his peak at age 27, when he posted a 168 wRC+, but 11 (!) years later, he put up a 164 wRC+ and a 166 wRC+ in back-to-back seasons, with a wide range of average to well-above-average seasons in between. There’s no curve to his performance over the years — just a somewhat wiggly line at the top of the graph.

In reality, most big leaguers don’t age like Cruz, try as they might. Given his past, one could suspect him of using banned substances, but in response, he has pointed to the negative test results accumulated over the years since 2013. Instead, he credited his finely tuned training and recovery routine, which teammates and trainers spoke of using the same tone reserved for legends and tall tales. As Twins strength and conditioning director Ian Kadish once put it, “He’s defined the fountain of youth.”

Cruz, though, isn’t merely a point on an aging curve or a one-dimensional video game character with a powerful bat. He doesn’t leave behind a career defined by any singular feature or moment, but rather a glowing example of what it means to be a full-spectrum human with bad decisions alongside a childlike joy for a game and mountainous screw-ups that take over a decade to undo alongside a bottomless pit of generosity. We’ll remember him as the Boomstick, but the Boomstick is more than a bat.

It’s also a hot dog.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-anti-hero-of-the-aging-curve-calls-it-a-career/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions