Vincent Carchietta-USA TODAY Sports

Juan Soto is a tricky player for me to write about, because the numbers speak for themselves — no literary flourish needed. Trying to get cute while writing about a guy performing miracles isn’t baseball blogging, it’s the Gospel of John.

Nevertheless, Soto is operating on such a level (he’s hitting .316/.421/.559 through the weekend — all stats are current through Sunday’s games) that it begs examination. Soto has the best batting eye of his generation; therefore, for him, every year is a walk year. But this season, specifically, is his final one before he hits the open market in search of a record long-term contract.

It’s been a complicated couple years for us Soto zealots. How can this player demand more money than the (deferral-adjusted) Shohei Ohtani deal? He’s never won an MVP and only finished in the top three once. He’s never recorded a 7-WAR season, never hit 40 home runs. He’s a bad defender, and in the past two seasons, he hit .242 and .275 respectively. If he’s such a uniquely valuable player, how come two teams gave up on him before he turned 25?

Soto suffers slightly in the public estimation because his greatest skill is invisible. Soto has posted a .400 OBP in every season of his career; since he debuted in 2018, nobody else has done that more than twice in a full 162-game season. He is the active leader in walk rate by 3.3 percentage points and the active career OBP leader by 27 points, both over Aaron Judge.

Soto is still one of the most selective hitters in the majors — out of 171 qualified batters, he has the fifth-lowest overall swing rate and chase rate — but by his standards, he’s been quite aggressive this season. Soto is currently running, albeit by a tenth of a percentage point, the lowest walk rate of his career. That’s accompanied his lowest-ever strikeout rate. And when he makes contact, he’s doing more damage; Soto currently has the highest wOBA and xwOBA of his career, with the exception of his 47-game 2020 season.

This past winter, it was fashionable to suggest that Soto would adapt his game to playing in the Bronx. After all, this is a very strong left-handed hitter who’d just come from San Diego and its famous pitcher-friendly ballpark. Now, Soto would be playing his home games at Yankee Stadium, an edifice whose dimensions were built to suit 100 years’ worth of pull-happy lefty power hitters.

Soto might not be as big as Judge or as thirsty for home runs as Babe Ruth, but he can count to 314 — the distance, in feet, from home plate to the right field foul pole at Yankee Stadium. That’s not very far.

I was skeptical; when Soto puts a charge into the ball, he can hit it out. Soto is currently eighth in career HR/FB%, leading — among others — Bryce Harper, Pete Alonso, and Austin Riley. But he’s traditionally been rather groundball-happy. We’re into year three of international forehead-smacking over Vladimir Guerrero Jr.’s inability to do anything but smash the ball incredibly hard right into the dirt in front of home plate. Soto and Guerrero actually have identical career groundball rates, and Soto’s GB/FB ratio is a couple hundredths higher.

Changing that part of his game would carry great risk for Soto; terrestrial as his batted-ball profile might be, the 25-year-old is working on his seventh straight season with a wRC+ over 140. It is most decidedly not broke. Soto is, in fact, pulling the ball slightly more than he ever has, and running his lowest GB/FB rate since 2019.

But this early-season explosion is not the result of Soto hunting Ruth’s short porch. He’s hit eight home runs, which puts him on pace for 36 over a full season — exactly one more than his previous career high. Only two of Solo’s dingers have gone out to right field at Yankee Stadium, and both of them would’ve gotten out of every stadium in the majors. Soto’s pull rate of 41.7% is just 68th out of 171 qualified hitters. And as a matter of fact, Soto’s pull rate on fly balls is the lowest it’s been since his rookie year, as is his fly ball rate on balls hit to the pull side.

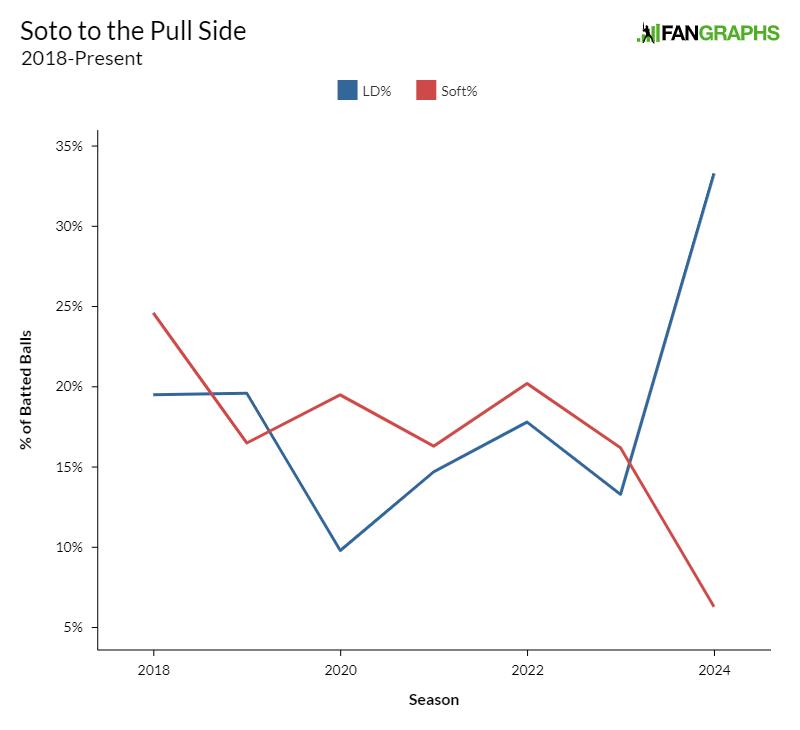

What Soto is doing is hitting the absolute bejeezus out of the ball, but on a relatively low trajectory. Soto is in the bottom 10% of qualified hitters for fly ball rate on balls hit to the pull side, but he’s in the top 5% in line drive rate. Here’s what Soto has done every year on batted balls to the pull side. The blue line is line drive rate (more is better), and the red line is soft contact percentage (less is better):

This is a specific area of improvement for Soto, but he’s hitting the ball incredibly hard all over the place. What was merely plus or plus-plus power is now among the best in baseball, non-Judge/Ohtani division:

Juan Soto Is Hitting the Ball Harder

| Year |

EV50 |

Rank |

Out of |

| 2018 |

101.2 |

54th |

249 |

| 2019 |

102.1 |

38th |

250 |

| 2020 |

104.2 |

6th |

257 |

| 2021 |

104.6 |

11th |

232 |

| 2022 |

102.2 |

36th |

252 |

| 2023 |

104.5 |

9th |

258 |

| 2024 |

105.7 |

4th |

270 |

SOURCE: Baseball Savant

Finally, Soto is making better swing decisions. His O-Swing% is lower than it’s been since 2021, which was his best-ever MVP finish. His swing rate on pitches within the zone is higher than it’s been since before the pandemic. And when he does swing at pitches in the strike zone, he’s making more contact than ever and doing more damage. Soto’s xSLG on pitches in the strike zone is .702, which is his best mark since 2020 by almost 100 points.

Conversely, Soto is making less contact than ever on pitches outside the zone, which might sound like a bad thing at first. But actually, when a batter swings at a pitch outside the strike zone, a whiff is not necessarily the worst outcome. A hitter with limited strike zone judgment might try to square up a pitch outside the zone; a hitter like Soto might just get fooled on a pitch that ends up in an unexpected place and miss it altogether. And if a batter swings and misses, he famously gets two more chances. If he reaches out and rolls over to shortstop, he doesn’t get a do-over.

We think of hitters as following a developmental curve. As they get more experience, they make better decisions. As they get into their mid-to-late 20s, they get stronger and hit the ball harder. And eventually, they get old and their hands or eyes go, and the decline phase starts. A particularly precocious hitter might defy that aging curve; I remember waiting for Mike Trout to make another leap in his late 20s, but he was never really better than he was in his rookie year.

And it would’ve been fair to expect that of Soto. This guy was the best position player on a championship team at an age when most big league All-Stars are losing their shoes at a Chi Omega mixer. You want maturity? Soto came out of the womb with the discernment you’d expect from an ancient, serene god. Even as a 20-year-old, Soto hit like he’d been taking that borderline slider for 500 million years. How could he possibly get smarter and stronger?

We’re only six weeks into the season, but it looks like that’s exactly what happened. Soto has always worked miracles. Now he’s working better miracles.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-gospel-of-juan-soto/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions