A pair of gobblers duking it out during the spring season. Donald M. Jones

My eyes snap open when the toms gobble, my head swiveling like an owl’s. They’re close.

“Hear something?”

My dad is looking at me, eyebrows raised.

“Two,” I whisper, surprised. The gobbles were loud, carrying down the ridge. I hold up two fingers to be sure he copies. It’s already sunrise on opening day and we’re still listening for gobbles like a pair of desperate coyotes. Or at least, I’m listening. At 64, Dad can’t hear like he used to. I hadn’t realized how bad it had gotten in the years since we’d hunted together.

“Where are they?” He hitches a bulky pack higher on his shoulder, the only turkey hunter for a hundred miles without a vest.

“Up the hill, on the quarry road,” I say, checking my watch, then grabbing the gun and decoy bag at my feet. We’ve been waiting around on this two-track for an hour. “We need to move. Which way you wanna go?”

“You tell me. Can we go up and cut over?”

I shake my head. “I think we should sneak in from below, by the beaver pond.”

“Whatever you think,” he says, turning on the spot and unzipping his pants to take a leak.

“Pea Brains”

Most people enter their golden years somewhere around retirement. I think of this phase—roughly the last third of a natural human life—as the don’t-give-a-shit years. Dad hit his stride at 50.

Symptoms of not giving a shit include neither providing notice of intent to urinate nor stepping a polite distance (any distance) away to do so. If Dad’s outside, pissing is fair game. One may also scratch one’s back with a variety of odd and often dangerous objects, such as shed antlers, fireplace pokers, and clean forks that are returned to the silverware drawer from whence they came.

Conviction of always being right may also occur. Once, Dad and I made it just 10 minutes into a road trip before he threw the first punch of an hour-long fight. “I want to talk to you about something I know we don’t agree on,” he said solemnly. I looked over, alarmed he was about to dredge up politics, or religion, or extended family. He sighed. “Your perspectives on scent control are shortsighted and naive.”

A DAD LIKE MINE IS EMBARRASSING WHEN YOU’RE 13. BY THE TIME I GRADUATED HIGH SCHOOL, HE WAS HILARIOUS. AT 29, I’M TORN BETWEEN ADMIRATION AND EXASPERATION.

Swearing also becomes less filtered with age. As a teenager, I was delighted when Dad started dropping F-bombs around me. The worst insults in his vocabulary, however, remain G-rated. Lord help the unwitting “pea brain” cruising in the passing lane when he’s headed to camp. Worse still is “slob,” muttered like the four-letter word it is for a German Catholic with high blood pressure and a reverence for immaculate floors. Without order—gleaming skinning knives, color-coded wind charts for every treestand, a pickup with 115,000 miles that looks brand-new—the world would descend into darkness and chaos. By his reckoning, my sweaty camo and cluttered truck might as well be Sodom and Gomorrah. I’ve seen him field dress a deer exactly once, on the day he taught me how. I’ve cleaned his deer ever since. Guts make him retch, though he still offers pointers. He says I’m risking disease and—the horror—bloodstained camo by not wearing gloves. And not normal gloves either, but the plastic ones that go clear over your elbow, like I’m some kind of redneck debutante.

A dad like mine is embarrassing when you’re 13. By the time I graduated high school, I thought he was hilarious. At 29, I’m torn between admiration and exasperation. My hunting buddy is a control freak reveling in the lawlessness of old age.

“Oh, I Heard That One”

We make hardly any noise as we sneak into a cedar grove below the roost. There’s a small, sloping clearing and one place to set up. “Let’s sit there,” I whisper, nodding toward an old cedar just wide enough for both of us. My back hits the tree and, on cue, the toms gobble.

“You’re up, Dad,” I whisper. He doesn’t move. “Dad!”

“What?”

“Did you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“Gobbles,” I whisper. “Yelp back.”

Dad reaches for his box call, a Lynch’s World Champion that he bought in the early ’80s, and produces three uncertain yawps. Our tom is loud now, and I’m grinning underneath my facemask.

“Did you hear that one?”

“No.”

“He gobbled back. Heard one across the creek too, but he’s way off. Yelp again.” He drags the paddle a few more times. It sounds like the wreckage of a cattle gate creaking in the wind. I have enough sense to realize I’m no better, so I sit silently in judgment. But it doesn’t matter; the answering gobble is immediate and enthusiastic.

“Oh, I heard that one,” he says, sounding surprised to discover there really is a turkey nearby. Then, “Good, ain’t I?”

“Time to shut up, Dad.”

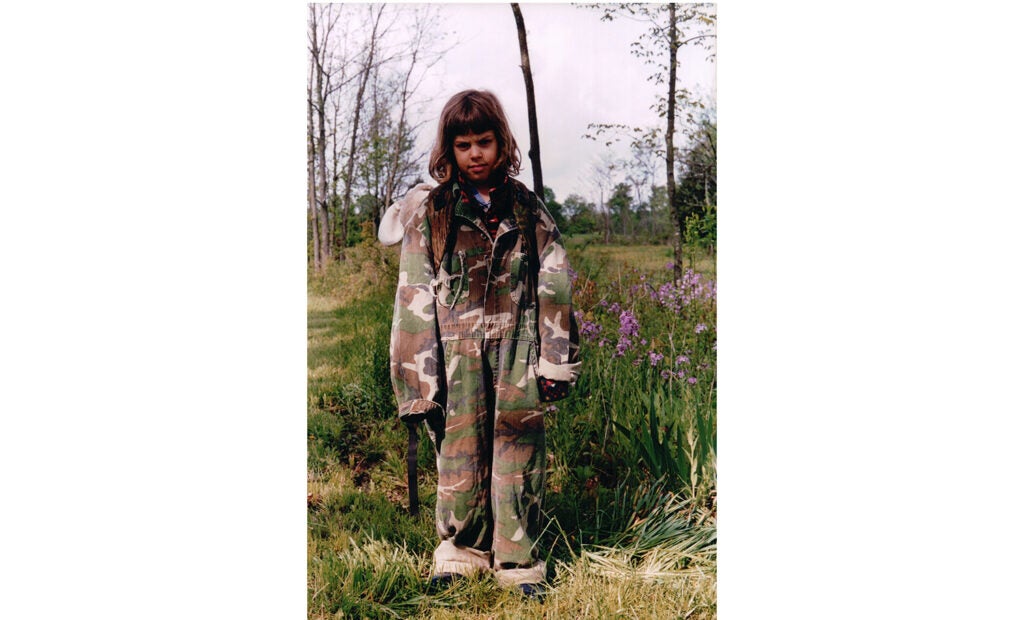

The author at 8, already skeptical after her first turkey hunt with her dad. Courtesy of Natalie Krebs

“She Saw Your Whole Face Moving”

I once hunted four seasons straight with Dad without even seeing a legal bird. He’d inevitably kill a tom before I arrived or after I left, but we’d never killed one together. The last time we sat together, he yelped in a hen with that same Lynch call. She walked into the field and then ran right back out.

“Well,” he said, throwing me a sidelong glance. “She saw you filming on your phone.”

“Me?” I watched his jaw work the gum I’d given him, the mashing exaggerated by the mask hanging off his chin. “She saw your whole face moving!”

My dad picks up hobbies the way he picks up the crumbs and gum wrappers I leave in my wake: often, and with relish. These hobbies include cycling, tae kwon do (my sister is still pissed about Dad meeting her college boyfriend for the first time, nunchucks in hand), woodworking, beekeeping, syruping, and golf. Before I got my learner’s permit, I would tag along to the golf course so I could drive the cart and keep him from picking fights with the pea brains who didn’t notice he wanted to play through. These men were drinking beer and chatting and generally having a good time. I tried to distract him by pointing out wildlife: deer, turkeys, barred owls. He would marvel at my sharp eyes, then tell me to floor it.

When Dad achieves proficiency at one hobby, he turns to the next. But he’s never stopped hunting, the most consuming pastime of his life. Whether it’s because he loves it too much or because hunting is impossible to fully master, I’m not sure. So we squabble over it, each knowing the other still has much to learn. While he never abandoned hunting, Dad went sparingly until I started to obsess over it too. His most recent fixation, food plots, keeps him from going solo into the turkey woods when there’s seed to spread or fertilizer to mix. But he always puts aside his to-do list to hunt with me. Everyone needs a hunting partner, no matter how ornery. So we argue, sure. But we’ll never run out of things to argue about.

“Can I Shoot Him Now?”

It’s silent in the clearing, without even the softest breeze rustling the trees. It’s been several minutes since the last gobble when I hear a branch snap. I stiffen, then realize it’s Dad. “What are you doing?”

“This branch is in the way if the other tom comes in,” he says.

I clamp my mouth shut and watch the trees, searching for movem—Snap. Snap. SNAP SNAP. The whole tree is shaking.

“DAD!” I hiss, really seething now. This he can hear just fine. Dad freezes, then puts his hands in his lap and doesn’t move again. One minute later, a blue head materializes where I’ve been glowering into the woods. “Don’t move. See the tom?”

For a heartbeat I think Dad didn’t hear. Then I realize he’s looking. We’re all frozen now, the bird transfixed by our jake deke, me marveling at the tom we haven’t spooked, and Dad wondering what the hell is going on.

“I don’t see him.”

“Twelve o’clock, straight up the hill.”

Another beat, and Dad shifts almost imperceptibly. He sees the longbeard. I know he wants to grab his shotgun, still by his side because I yelled at him not to move.

“Wait,” I whisper, watching the longbeard’s head flush an angry red. “Let him come in.”

I’m not videoing this time—I don’t dare move. The tom is just steps from thick timber. Dad is a good shot, but if he does miss, no one is making that follow-up. Besides, I heard two birds up here.

The longbeard slinks into the open, chest swelling. Then he pounces, raking the deke and pecking its neck. I forget about the possibility of a double, mesmerized. For 60 seconds, wingbeats and spurs on rubber are the only sounds in the clearing.

“Can I shoot him now?” Dad asks, deadpan, and I realize he just exercised enormous patience for me.

“Shoot him.”

The hunting buddies with an opening-day tom from the family farm. Courtesy of Natalie Krebs

“Whatever You Think”

As quiet as the woods were this morning, they’re alive with gunshots and distant gobbles as Dad walks ahead, longbeard over his shoulder. We try one more setup, then head back to camp.

“You know,” he says, pulling up a chair, “you yelling at me made more noise than those branches. That’s a natural sound turkeys hear all the time.”

I choke on my doughnut and wash it down with coffee, ready for a fight. “Not when that sound is coming from the same spot as the hen they’re after!”

He considers this. “Well, that’s true.”

I take another sip of coffee and swallow it with the rest of my points. I’ve learned a lot from my dad. Turkey hunting, but other stuff too, like people skills and road rage. “Whatever you think” really means “I think you are making a mistake.” And thinking you’re right all the time is an exercise in self-deception. It’s impossible to be right all the time.

“Here.” He hands me a plate to catch any more crumbs I might spray across his clean kitchen floor. “Well, that was really fun. I love watching them beat the shit out of the decoys like that. Are you taking me turkey hunting next year?”

The post Turkey Hunting with My Dad Is an Exercise in Trying Not to Kill Each Other appeared first on Outdoor Life.

By: Natalie Krebs

Title: Turkey Hunting with My Dad Is an Exercise in Trying Not to Kill Each Other

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/turkey-hunting-with-dad/

Published Date: Sat, 02 Apr 2022 12:00:00 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://manstuffnews.com/weekend-warriors/the-best-hiking-boots-for-2022

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions