David Butler II-USA TODAY Sports

The fastball is dead. Or is it?

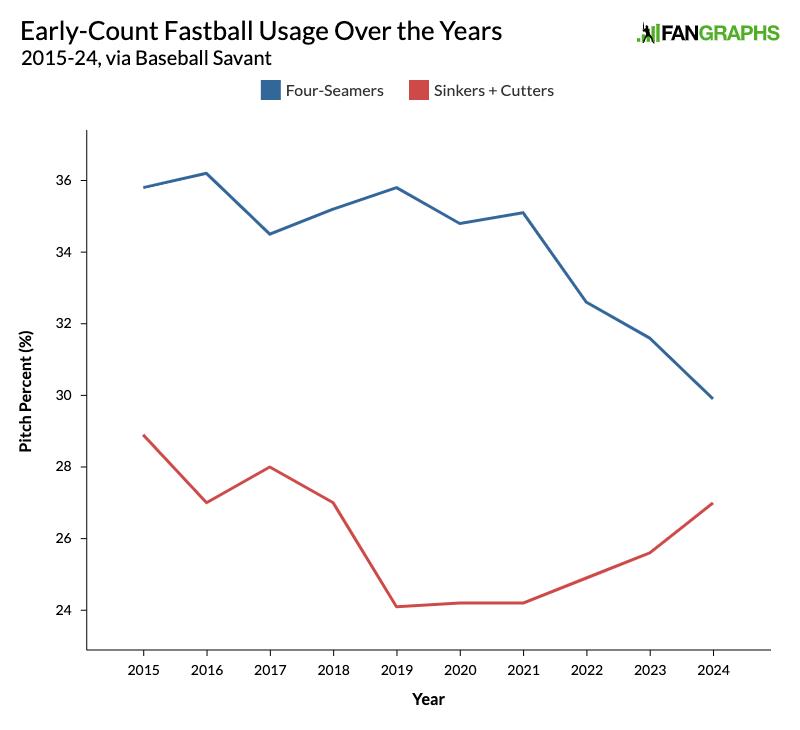

Every season has its share of articles detailing the league-wide decline in fastball usage, and 2024 is no exception. This time around, the spotlight has been on the Red Sox, who have seemingly crafted an elite rotation based on a delightfully succinct philosophy: Spin go brrrr. Indeed, they trail the league in four-seam fastball usage by a wide margin. But they’re also ninth in sinker usage and first in cutter usage as of this writing. This is incredibly interesting to me, especially after you consider the graph below:

In early counts (0-0, 0-1, and 1-0), when batters are more eager to swing and hunt for fastballs, we’ve reached a new minimum for four-seam fastballs. That checks out. But look at the combined rate of sinkers and cutters: It’s back up to levels last seen in 2018. So really, the Red Sox aren’t being hipsters. If anything, they represent what the league is thinking as a whole. The uptick is there, even if you exclude Boston.

The question is why? If you look at the metrics, it isn’t so obvious. Early-count four-seam fastballs return a higher xwOBA than sinkers and cutters, but that’s always been the case, and probably has been since those pitches were invented. And it’s not like sinkers and cutters have been performing better relative to their past selves. An interesting hypothesis is that for pitchers with average or below-average velocity, sinkers tend to be a better option. In their updated Stuff+ model, the folks at Driveline Baseball found that sinkers averaged higher stuff ratings than four-seamers up to the 97-mph mark, after which four-seamers took over at an exponential rate. Healthy slingers who live in that velocity band are still somewhat rare, so it makes sense that more “normal” pitchers might look to sinkers to shield them from hard contact.

Today, I wanted to share my answer to the question. I didn’t set out to find an answer – initially, I was looking at ways to analyze the effect of pitch sequencing – but baseball rewards you when you least expect it. As it turns out, sequencing and fastball usage seem intimately linked.

First, I collected pitch-level data from the 2022 and 2023 seasons. After much wrangling, I was able to figure out the pitch sequence of every plate appearance. The subsequent data ranged from first-pitch popups to 15-pitch stalemates, with everything in between. For the purposes of this project, I decided to make a few major (and debatable) decisions. First, I excluded plate appearances that ended in a hit-by-pitch, walk, or strikeout. Ruling out hit-by-pitches was the easiest choice: They’re the product of poor control, not sequencing. Walks have a little more to do with sequencing, since the right order of operations could coerce a batter into swinging at balls off the plate. Still, I’d argue that they’re much more a product of command and stuff. I seriously considered including strikeouts in the set of outcomes, but at this point, with hit-by-pitches and walks by the wayside, I thought it would be more intriguing to isolate balls in play.

Second, instead of relying on literal outcomes, I calculated the expected run value of each batted ball based on the angle at which it was hit, the count, and whether the pitcher had the platoon advantage. Doing so accounted for several things. For one, pitchers exert far more control over launch angle than exit velocity, so it makes sense to reward (or penalize) them for the former. Inducing contact in an unfavorable count is also better on average, by run value, than inducing contact in a favorable count. Lastly, the platoon advantage extends to balls put in play. For example, righty-on-righty sinkers are regulars at the Salty Spitoon, but you can find righty-on-lefty sinkers lying on the floor of Weenie Hut Jr.’s, crying in shame. One last thing: I added sequence length as a variable, which accounts for the moderate negative linear relationship between the length of a sequence and run value.

With the data patched up and ready to go, my model of choice was a random forest, which uses an ensemble of decision trees to make predictions. If you’ve seen a decision tree before, you’ll notice that it resembles the cognitive process a pitcher might go through when selecting a pitch sequence: You start off with an initial pitch, after which the number of possible paths forward increases at an overwhelming rate. (If I was a professional pitcher, my chronic indecisiveness would be my downfall). I’d like to emphasize, though, that using machine learning is not necessary here. In fact, it’s probably overkill. But I needed the practice, and besides, building models is fun! It’s very involved, unlike querying data. Much of the methodology was heavily inspired by this article from Dylan Drummey, and I can’t thank him enough.

That was a lot. But now we can zip to the fun part. If you were choosing a first pitch, and your goal was to minimize damage on contact, which offering should you go with? Here’s what the data says, in order of model-predicted run value:

Best First Pitches

| Pitch 1 |

Predicted Mean RV |

| Sinker |

0.0184 |

| Cutter |

0.0300 |

| Four-Seam |

0.0354 |

| Changeup |

0.0389 |

| Slider |

0.0437 |

| Curveball |

0.0500 |

It looks like sinkers and cutters are the way to go. Four-seam fastballs and changeups are neutral pitches, while sliders and curveballs get slammed if hitters do manage to make contact against them. In reality, if you query actual sequences rather than model the outputs, these pitches also appear in this exact order. But maybe you sort of knew this already. I’ll admit, these aren’t the most interesting results, though they are useful in validating that the model isn’t stuck in la-la land. So instead, let’s move on to the best two-pitch sequences:

Top 10 Two-Pitch Sequences

| Pitch 1 |

Pitch 2 |

Predicted Mean RV |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

0.0076 |

| Sinker |

Sinker |

0.0137 |

| Sinker |

Cutter |

0.0196 |

| Sinker |

Slider |

0.0205 |

| Sinker |

Changeup |

0.0264 |

| Cutter |

Sinker |

0.0282 |

| Cutter |

Four-Seam |

0.0291 |

| Four-Seam |

Four-Seam |

0.0298 |

| Cutter |

Changeup |

0.0311 |

| Cutter |

Cutter |

0.0330 |

The formula for starting off a sequence hasn’t changed. But the column of second pitches does subvert expectations. Rather than change eye levels with an offspeed or breaking pitch, the model suggests that you should fire off another fastball, preferably one of a different variety. It’s the notion of a subtle change, of just a couple of miles per hour and a couple of inches. Somewhere between the old school coach who wants you to pound the zone with a heater and the Gen-Z analyst who’d like to see 10 breaking balls in a row, here we are. Fastballs are still good, yes, but there’s a nuance to them. Will we come to a similar conclusion with three-pitch sequences?

Top 10 Three-Pitch Sequences

| Pitch 1 |

Pitch 2 |

Pitch 3 |

Predicted Mean RV |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Cutter |

0.0038 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Slider |

0.0051 |

| Sinker |

Sinker |

Curveball |

0.0053 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Four-Seam |

0.0057 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Sinker |

0.0085 |

| Sinker |

Sinker |

Sinker |

0.0109 |

| Sinker |

Cutter |

Curveball |

0.0151 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Changeup |

0.0156 |

| Sinker |

Slider |

Four-Seam |

0.0157 |

| Sinker |

Slider |

Four-Seam |

0.0161 |

Unfortunately, this is where the model begins to show its weakness. Here’s what I think is happening: Because sinkers are undoubtedly the best first pitch to throw for contact suppression purposes, the model overcorrects and assumes that any sequence that starts with one is infallible. As a result, the longer a sequence, the weaker the correlation between the predicted and actual run values becomes. I couldn’t figure out a way to address this, so from now on, we’ll also rely on empirical evidence:

IRL Top 10 Three-Pitch Sequences

| Pitch 1 |

Pitch 2 |

Pitch 3 |

Actual Mean RV |

| Sinker |

Cutter |

Sinker |

-0.0562 |

| Cutter |

Four-Seam |

Curveball |

-0.0482 |

| Sinker |

Changeup |

Curveball |

-0.0266 |

| Cutter |

Curveball |

Slider |

-0.0262 |

| Curveball |

Changeup |

Curveball |

-0.0193 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Curveball |

-0.0126 |

| Cutter |

Four-Seam |

Slider |

-0.0126 |

| Sinker |

Slider |

Curveball |

-0.0098 |

| Changeup |

Sinker |

Changeup |

-0.0066 |

| Sinker |

Four-Seam |

Sinker |

-0.0057 |

These results are more realistic. We see a few more sliders, curveballs, and changeups pop up, and the overall variety seems to reflect how the average pitcher navigates an at-bat. And yet…

- Eight of 10 first pitches are either a sinker or a cutter. The remaining two are non-fastballs. There is not a single four-seamer to be found.

- Instead, four-seamers can be found living in second pitch land. This seems to suggest, once again, the importance of changing fastball types. Six of the 10 second pitches are fastballs.

- The pattern breaks with third pitches: Now, breaking and offspeed pitches dominate the list. Three fastballs in a row might be pushing it. That said, the number one sequence is sinker-cutter-sinker.

- Overall, for a supposedly dead pitch type, the fastball is prominent.

But let’s think about this for a moment. If these observations are true, why has there been such a widespread effort to eliminate the fastball?

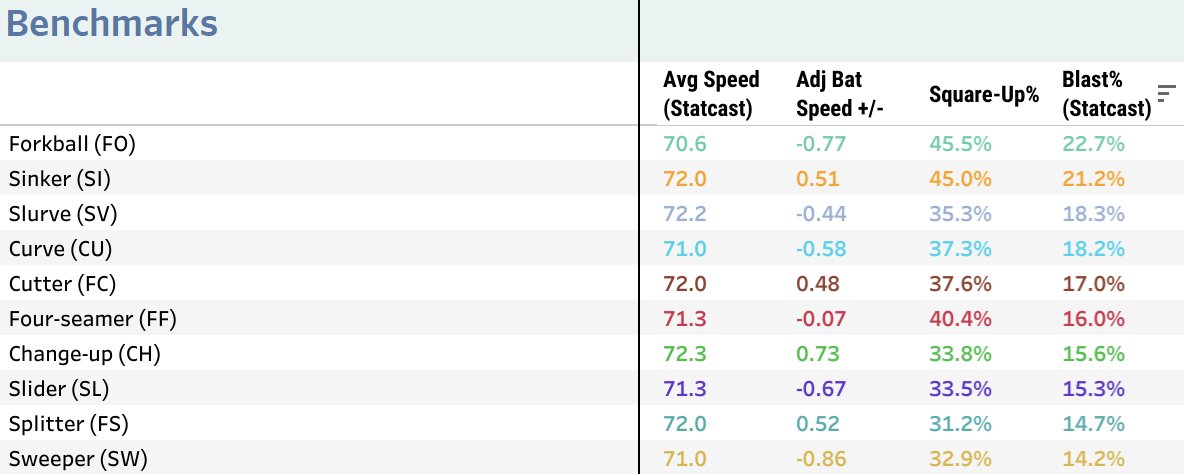

In his analysis, Drummey came to the opposite conclusion: Curveballs and sliders had the lowest predicted run values, while cutters and sinkers had the highest. This doesn’t mean one of us is catastrophically wrong. The main culprit here is the curse of pitching: What is good for contact suppression (as defined by launch angle) is generally bad for getting swings and misses. Take the sinker as an example. Year after year, it leads all pitch types in groundball rate. At the same time, it is last in whiff and chase rate, and as recent bat tracking data indicates, it’s easy for batters to square up. If you exclude strikeouts, walks, and exit velocity as I did, you’d end up overrating the sinker and underrating, say, the slider, which in many respects is everything a sinker is not. The slider leads all pitch types in whiff and chase rate, and is troublesome for batters to square up. Via Alex Chamberlain:

This is why the sinker isn’t too popular, and why it isn’t dominating the league. If you only consider their innate qualities, sliders are decidedly superior to sinkers. Ideally, a pitcher would throw nothing but sliders on the outer edge of the plate, basking in glory every outing. But this isn’t a perfect toy world where all other things can be held equal. Some pitches dot the corners; others end up in the middle. Breaking balls need to be set up with fastballs in order to achieve their full potential. And not every hitter is vulnerable to spin. At some point, you’re going to have to throw a fastball and hope for the best. The most prudent option, then, is to be smart about what fastballs you throw, how you throw them, and when.

Certain aspects of “how” have already been addressed. For the most part, the league is on board with both the high fastball, and with throwing fewer fastballs, period. But the “what” and “when” are largely uncharted territories. The results from our model could be an illuminating map. We’ve seen that the best way for pitchers to suppress contact – in other words, to minimize the possibility of detrimental launch angles – is to embrace a wide variety of fastballs. Not just four-seamers, but also cutters and sinkers.

Order matters, too. The fastball triumvirate should be used early in the count, not when hitters fall behind. If you look at the league-wide combined sinker and cutter usage in counts that favor the pitcher, you’ll find that it’s actually at an all-time low. The gap between it and the aforementioned early-count fastball rate is solid evidence that some teams are looking to attack with sinkers and cutters first, changeups and sliders second.

It’s surprising how this resembles a more traditional approach to pitching. For a century, pitchers established the count with their fastballs, then pivoted to a wipeout pitch once they had two strikes under their belt. The act of pitching backwards, which reverses this order, is associated with the modern game, even if it did exist in days past. But it’s worth noting that pitching backwards is usually accomplished through a four-seam fastball, not a sinker or a cutter. In this context, the four-seamer is not a broad stroke of the canvas – it’s a finishing touch, intended to produce a strikeout.

Circling back to the initial question, I don’t think the league is trying to eliminate the fastball. Instead, I suspect there’s been a collective effort to reframe the very definition of a fastball. If you viewed a fastball as a primary pitch and only a primary pitch, it makes sense that you’d want to use it as much as possible. The word “primary,” in the language of baseball, implies volume. But if you viewed a fastball as a flexible construct, maybe you’d start to think outside the box. You end up realizing that a fastball with the right shape can be viable in two-strike counts. And you may end up discovering that using multiple types of fastballs in conjunction with each other is much more effective than relying on just one.

I’m a little hesitant to make sweeping claims about what certain teams or an entire league is up to, since pitch usage is dictated by which players are on which roster at a given moment. But I’m sold on the idea that it can’t hurt to have more than one fastball. It won’t dramatically alter someone’s life, and this is by no means a revolutionary concept, but I think an extra fastball (or two!) could aid pitchers who normally struggle to keep the ball on the ground. The evidence is there. It won’t require a mechanical overhaul, and it doesn’t need to blow opposing hitters away. All it needs to do is divert them. Tyler Glasnow, who has started to experiment with a sinker, is a great example.

The kitchen sink has returned, and fastballs are lending it a helping hand. The traditional way of using a fastball might be dead, but the pitch itself continues to show up – in new outfits, that is.

Source

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/one-fastball-isnt-enough/

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions