Tim Robinson sticks a big lionfish beside an artificial reef. Rayna O’Nan

ON ANY GIVEN weekend this summer, there’s a lionfish derby underway in Florida. As the lionfish population has exploded in recent years, so too has interest in targeting the invasive critters. Tournaments begin in late winter and stretch into the fall, with cash and other prizes incentivizing already-motivated spearfishermen to remove as many destructive fish as they can from vulnerable coral reefs in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. (The species is notorious for its voracious appetite: A single lionfish residing on a reef can reduce native reef fish recruitment by as much as 79 percent.)

The world’s biggest lionfish derby is the Emerald Coast Open, held in Destin, Florida, in mid-May. This year our photographer tagged along with one of the participating teams, captained by spearfisherman Tim Robinson. At 62, Robinson is a scuba instructor and the owner of ZooKeeper, which makes a sort of underwater creel for safely storing lionfish during dives and sponsors lionfish derbies across the state.

“This is not a problem that we’re going to eradicate. Lionfish multiply worse than rabbits,” says Robinson. “A female lionfish lays between 15 to 30,000 eggs every four to seven days, year-round. To put that into perspective, [participants] removed roughly 25,000 lionfish during this two-day derby, and then about a little over 5,000 in the pre-derby that started in February. And that’s basically the number of eggs that one female lionfish lays once a week.”

“This is not a problem that we’re going to eradicate. Lionfish multiply worse than rabbits.”

—Tim Robinson

Not all the eggs in a clutch survive, of course, but Robinson’s math problem helps illustrate the sheer scale of the lionfish invasion. While he enjoys the larger mission of lionfish management, Robinson spends his weekend spearfishing for another reason.

“The truth is that we love it. We love spearing lionfish,” says Robinson. “It’s the thrill of the hunt. They’re not just out swimming around freely. In most cases, you have to hunt for them. It’s fun to come up with a dozen lionfish or a full ZooKeeper. I’ve had days when I couldn’t get any more lionfish in my ZooKeeper. It’s just a great feeling. So yes, we want to be part of the cause [to reduce lionfish] and do our part. But we really, truly love it. It’s just in our blood.”

Cody Robinson (left), 26, prepares to dive; Rob Robinson (right), 28, makes a standard back roll off the boat into the water. During the derby Robinson’s team dove in alternating pairs, using the buddy system for safety and keeping two divers in the boat to clock their mandatory surface time. (This allows divers to “off gas,” or exhale excess nitrogen absorbed from their tank’s air supply.) The Robinsons mostly targeted lionfish around 90 to 100 feet deep during this derby. Rayna O’Nan

Cody spots a lionfish before his ZooKeeper even hits the ocean floor. The team didn’t find many lionfish at this wreck, and later they chatted with a team who had fished it before they arrived. Rayna O’Nan

A lionfish conceals itself behind a rock as Tyler Bourgoine hunts nearby. Although the fish are native to the Indian Ocean, they blend in easily with Florida’s natural and artificial reefs. A single lionfish sports 18 venomous spines: thirteen along its spine, three near the anal fin, and one on each side. Robinson says getting poked by any one of them is “about 10 times worse than a bee sting.” Divers who are stung should return to the surface and try to break down the venom by applying a heat pack; Robinson keeps these handy in his dive kit. Rayna O’Nan

“We’re trying to protect the reef from the lionfish,” says Robinson, who never wants his spear to pass through a fish and strike the reef. Careful shot placement is key. “You basically swim right up to a lionfish, and you can actually touch them with your spear and maneuver them. You want to move him around a little bit. Because they don’t have a predator [here], they’re not afraid of you. As a general rule, they’ll let you come right up to them and put the spear within a couple inches before you shoot them.” Rayna O’Nan

Tyler (left) and Cody close in on a trio of lionfish. Although most lionfish are unfazed by divers swimming up to them, lionfish that have been shot at before are skittish. The invasive critters hide beneath ledges or in holes in the reef, making a bright dive light essential for successful hunting. “They can blend in with whatever they’re around,” says Robinson, who offers spearfishing education classes for divers. “I always say to think like a lionfish. Like if I were a lionfish, where would I be? And that’s typically under a ledge. They actually invert themselves and go belly up underneath one. Half the fish I shoot are typically upside down.” Rayna O’Nan

Cody (Right) fistbumps his dad, who just speared a big lionfish. The Robinsons are hunting with homemade sling spears (also known as Hawaiian spears), which are about 3 feet long and tipped with three to four prongs. They’re often barbed to prevent losing fish, and some divers put up to seven prongs on their spears, though Robinson considers this overkill. Rayna O’Nan

Rob stuffs a lionfish into his ZooKeeper. All lionfish divers use some sort of lionfish containment device for a few reasons. Spearing a lionfish doesn’t usually kill it, so divers must trap them somehow. It also protects against venomous stings and provides a handy carrying case for toting fish back for weigh-in and, eventually, eating. Rayna O’Nan

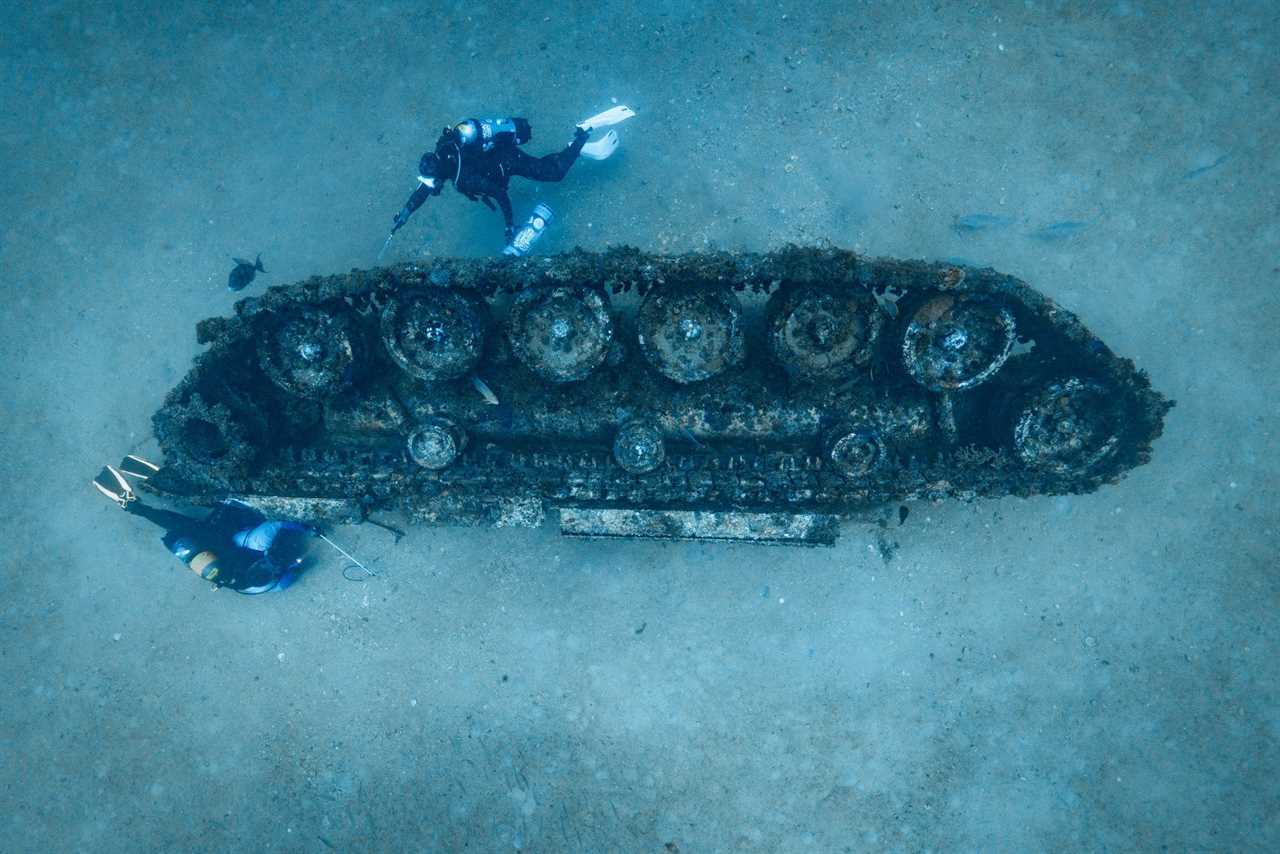

Cody (top) and his father check an old tank. Lionfish are nocturnal and primarily hunt at night, but they’re also opportunistic predators. “They eat to eat, not because they’re necessarily hungry,” says Tim Robinson. “They eat because there’s something in front of them to eat. They’re not selective. As long as it will fit in their mouth, they’ll eat it. We catch them with their bellies so bloated, because their bellies will expand 30 times to accommodate what they’re eating.” Rayna O’Nan

Keeping tabs on his dive computer, Cody swims to the surface. Divers are not supposed to ascend faster than 1 foot per second to avoid decompression sickness, known as the bends. Rayna O’Nan

Surfacing with fresh lionfish hauls. The Robinsons hired a charter captain who was willing to take them scouting ahead of the derby, plus drive them around for two dawn-til-dusk days on the water during the competition. Rayna O’Nan

Handing off a ZooKeeper stuffed with lionfish. Rayna O’Nan

Rob empties a load of lionfish into the boat cooler. The team kept the fish on ice all day before returning to the weigh-in. Rayna O’Nan

Rob holds up two of the team’s bigger lionfish from the first day of the derby. Rayna O’Nan

The ZooKeeper team poses for a quick group photo. From right, front: Tim Robinson, Tyler Bourgoine, Rob Robinson, and Cody Robinson. Their dive master and charter captain stand behind them. Rayna O’Nan

Buckets of lionfish back at the dock. A total of 24,699 lionfish were removed by 144 participants at the Emerald Coast Open in Destin. The fish were cleaned and taken home, given away, or served by Destin restaurants. Lionfish is a mild white fish that tastes great anyway you prepare it, says Robinson, though he likes it fried best. Rayna O’Nan

Each lionfish submitted for the derby was carefully measured, with prizes awarded for the largest and smallest fish, as well as most lionfish removed. The largest measured nearly 18 inches long, earning that team a $5,000 check. Rayna O’Nan

Deep Water Mafia I won the top prize of $10,000 for spearing the most lionfish: 2,898 fish in two days. After Robinson and his team finished in 12th place in the 2022 tournament with 305 fish, his sons were determined to win this year’s tournament—not for the prize money, which Robinson declines as a sponsor, but for the challenge. The ZooKeeper team buckled down and speared 509 fish this year … and still came in 12th. Robinson chalks that up not to an increase in competition among participants but to the exploding lionfish population. Rayna O’Nan

Read more OL+ stories.

The post Photos from the World’s Biggest Lionfish Derby appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

By: Rayna O’Nan and Natalie Krebs

Title: Photos from the World’s Biggest Lionfish Derby

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/fishing/spearfishing-invasive-lionfish/

Published Date: Wed, 05 Jul 2023 22:31:25 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://manstuffnews.com/weekend-warriors/this-is-the-largest-carp-ever-caught-by-a-female-angler-in-britain

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions