A dead brown found on the Big Hole this June. Big Hole Lodge

In May, a coalition of more than 30 fishing guides sounded the alarm about the historic trout declines taking place in Montana’s Jefferson River Basin. Fed up with what they saw as a slow response to a serious problem, the guides wrote a letter to Gov. Greg Gianforte demanding that more action be taken by the state.

“We have an emergency in southwest Montana’s rivers, and we need to act immediately to avoid a total collapse of those trout fisheries,” they wrote. “This is an all-hands-on-deck moment.”

The Jefferson River Basin, which includes the Big Hole, Beaverhead, and Ruby Rivers, comprises some of the most productive trout water in the West. The three streams (and the main stem of the “Jeff”) have historically supported thousands of wild trout per mile, along with prolific bug hatches that draw anglers from all over the U.S. But in recent years, the Basin’s trout populations have taken a nosedive due to low water levels and a mysterious disease that no one has a handle on.

The growing frustration over the state of these fisheries was compounded by the fact that the region lacked a fisheries manager for two years, not to mention a full understanding of what’s driving the declines.

Finally, Gov. Gianforte held a meeting on Friday at a packed community center in Wise River. He tried to assure the crowd that Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks had formed an adequate response to trout declines in the Basin. This news was welcomed by the locals. It was also long overdue, which only underscores the fact that it could be some time until we fully understand the crisis at hand.

The Lowest Fish Counts on Record

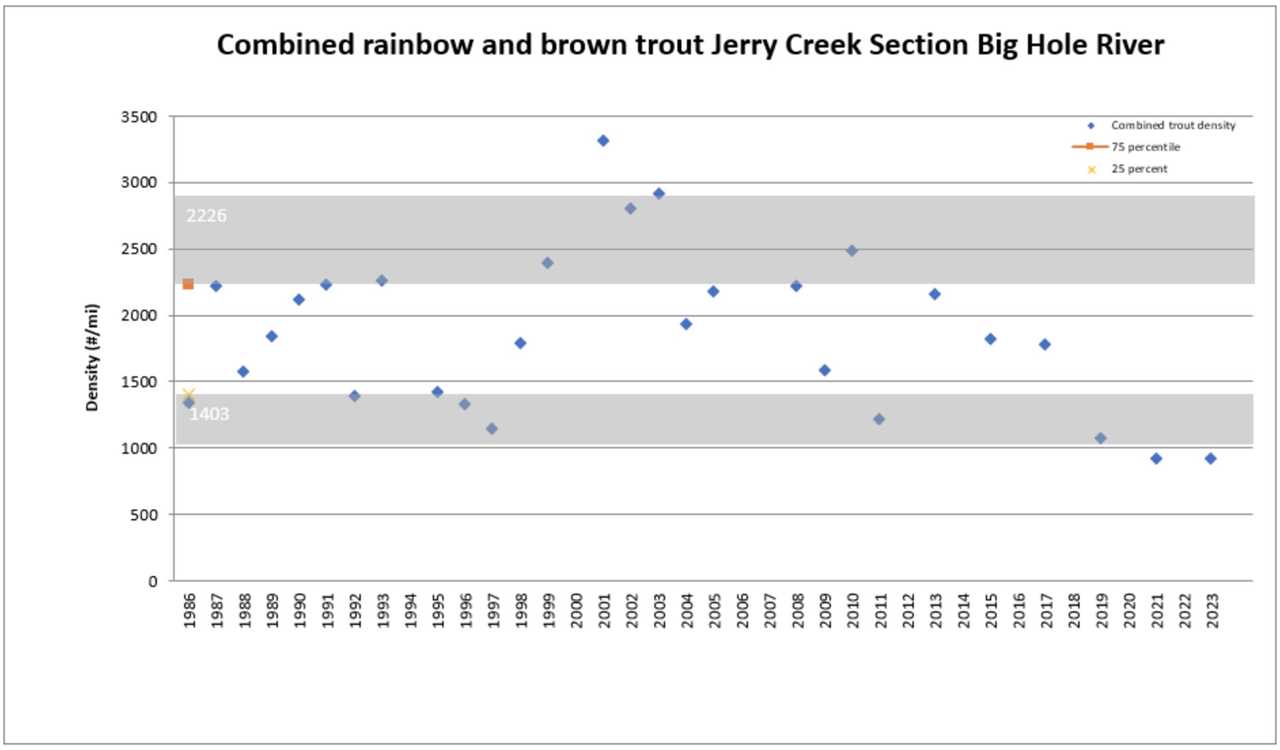

In the Big Hole River, fisheries biologists with MFWP are seeing the lowest numbers of brown and rainbow trout since record-keeping began in 1969. Similar declines have been recorded on the Beaverhead and Ruby Rivers, which along with the Big Hole flow into the Jefferson—one of three main forks that form the Upper Missouri River.

The most recent fish counts on the Jerry Creek Section of the Big Hole show fewer than 1,000 brown and rainbow trout per mile. That’s compared to roughly 1,750 trout per mile in 2017, and it’s a third (at best) of the 3,000 to 3,500 trout per mile that were counted along the same section in 2000.

“We’re talking about the lowest fish counts on record in the Big Hole, Ruby, and lower Beaverhead. It’s bigger than a singular river,” says Brian Wheeler, a fly-fishing guide at Big Hole Lodge and the executive director of the Big Hole River Foundation. “This is a basin-wide crash at the headwaters of the Missouri River, and we’re right in the middle of it.”

Trout populations in the Big Hole peaked in the early aughts, and they’ve trended downward over the past 11 years. Courtesy MFWP

Trout populations in the Basin have trended downward over the past 11 years, and scientists will point out that other streams in southwest Montana have seen their trout populations dip recently during low water years. But they also agree that something more troubling seems to be taking place on the Big Hole.

“We’ve seen declines—[but] nothing on that magnitude,” MFWP fisheries biologist Jim Olsen told the Montana Standard last month. “In the past, they’ve really followed water. And so, during drought times, populations [on the Big Hole] would decline. But we’re talking a 20 to 25 percent decline.”

What makes these low numbers even more concerning is that no one knows exactly what’s causing them. As Olsen and others have pointed out, low, warm water has been linked to trout declines in rivers across the Intermountain West. But brown trout are usually more tolerant of warm water than rainbow trout and native cutthroat throat—which also inhabit the Big Hole—and the browns seem to be faring the worst out of the three.

Low water conditions on the Big Hole River in September 2021. Brian Wheeler

“It’s the browns that seem to be the ones getting this disease—this fungus—whatever it is,” Wheeler says. “Another odd aspect is that the rainbows aren’t increasing to fill the voids the browns are leaving. And then you have cutthroat, which seem to be doing great. These are some things that don’t quite make sense and lead us to think there is an additional factor at play that’s probably disease.”

Olsen and other biologists found several of these dead, fungus-covered browns in the Big Hole last fall. They say the only way to positively identify the mystery disease is to bring a live tissue sample from a living fish to a histopathologist in a lab. But the agency has so far been unable to pull this off.

This spurred Big Hole Lodge owners Craig and Wade Fellin to launch the Save Wild Trout campaign in the spring. The group partnered with Yeti to acquire some coolers that were retro-fitted with aerators. These serve as temporary fish tanks, and they could be essential in helping the guides achieve their number-one goal: getting a live-but-dying brown trout into MFWP’s hands.

Filled with water and retro-fitted with an aerator, a Yeti cooler serves as a temporary fish tank. Courtesy Save Wild Trout

“We’re just trying to get this done as quickly as possible, and the best-case scenario is providing an answer so the state can chart a path forward,” Wheeler says. “We’ve had a few situations where a guide caught a sick fish, rowed down and wasted their day to get to the boat ramp—but didn’t care because this is as close as anybody has gotten to getting a sick fish to a biologist. Then they got to the takeout where they had service, but the fish didn’t quite make it because there was nobody available to come meet us at the boat ramp.”

The Mysterious Fish Fungus

Mike Duncan, who was hired as the Region 3 Fisheries Manager just three weeks ago, says he understands the frustrations voiced by the outfitting community.

“I get it. I get that folks worry that we’re not being proactive or responsive enough, but we’re working on it best we can.”

A former fisheries biologist on the Madison River, Duncan points to the agency’s recently announced four-pronged response to trout declines. This includes three key studies into fish mortality, recruitment, and any potential diseases that could be impacting populations. The three studies are slated to begin sometime in 2024. This feels like an eternity for the guides and private anglers, who are now trying to work in tandem with the state to speed the process up. In the meantime, Duncan is working to better understand what’s killing the trout.

“The fungus on their sides, that’s saprolegnia. We know what that is,” Duncan tells Outdoor Life. “But these other lesions we’re seeing on the top of their heads, tails, and bellies. We don’t know what exactly is causing that, and saprolegnia could be a secondary effect from that.”

A handful of dead, fungus-cover browns that MFWP biologists came across in November 2022. Courtesy MFWP

Duncan points to the new online portal that FWP launched in July, which allows the public to report sick or dead fish to the agency. (This represents the fourth “prong” in MFWP’s ongoing response.) And he says that as much as he’d like to see a sick brown trout tested in a lab, it’s not always that easy. There aren’t many histopathologists who can run this specific live-tissue test, he explains, and the agency’s staff is already spread thin across a large geographic area.

“I think we need to have realistic expectations on how we can respond to these calls,” Duncan says. “The one that came through the other week … I was finishing up a meeting and hit the road to head over there, and then the fish died before we got there.”

Duncan adds that while the moribund browns are a real concern, it’s not like every brown trout in the Big Hole is sick or dying. He and other biologists have spent days on the river looking for sick trout without finding one.

“I get that when you see a dead or dying fish, it’s concerning … especially when you have a population that is at or near historic lows,” Duncan says. “And when the biologists can’t tell you exactly what it is—I understand why the public wants answers. And we’re gearing up to get them those [answers].”

Declining Water and Quality Concerns

The myriad problems plaguing the Big Hole might not be fully understood just yet, but two things are certain. They aren’t unique to southwest Montana, and they all tie back to a shortage of cold, clean water.

Flows in the Big Hole Rifer are wholly dependent on snowpack, but the region has been getting less snow in recent years. Brian Wheeler

Below-average snowpack, weakened runoff, higher water temps, lower soil moisture levels, and longer fire seasons. As the effects of climate change bear down on watersheds across the West, many of the people whose livelihoods are tied to these rivers start blaming one another. And on the Big Hole, this conflict is too often portrayed as the fishing community versus the ranchers.

Beaverhead County is home to more cows than any other county in Montana, and cattle operations have long been linked to poor water quality. Wheeler runs a water-quality-monitoring program at various points along the river, and he’s seen nutrient-loading issues with some stretches containing high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. He also says that since some irrigators don’t measure how much water they use, it’s hard to determine the amount of water being taken out of the system at any given time.

“We know we have nutrient problems, but I want to say explicitly that this is not a ranchers versus fishermen debate,” Wheeler says. “The whole ‘cows not condos’ thing is a real mentality out here and we hope that ag stays on the landscape. These problems are not unique to here. They’re also not unfixable.”

Excessive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus can cause algal blooms, which consume oxygen and kill trout. This photo was taken in 2022 near the Big Hole’s confluence with Mud Creek. Brian Wheeler

This is where the Big Hole Watershed Committee is trying to make a difference. Executive director Pedro Marques explains that the group was formed to get ranchers engaged in voluntary conservation, and so far, they’ve been successful. Marques and Wheeler both point to the Arctic Grayling Recovery Program, which is run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and supported by MFWP. The program relies on dozens of ranchers along the river who’ve either cut down on their water use, engaged in restoration work, or both—all with the common goal of preserving one of the last viable grayling populations in the Lower 48.

“These ranchers are doing the best they can,” Marques says. “We know there are improvements to be made, like installing water measurement devices at diversion points and making headgates more efficient to operate. And if we can find some spots where we can help ranchers move their production and concentration of cows further from the river—those are relatively easy projects once we identify them.

“But based on our drought management plan that we’ve had for 20-something years, ranchers have been giving back water, and they’re all trying to share in that sacrifice for the river’s sake,” he continues. “The hard truth of the matter is that these landowners could dry up the river tomorrow and not break a single law.”

Volunteers with the Big Hole Watershed Committee work on a river restoration project on a tributary of the Big Hole. Courtesy Big Hole Watershed Committee

Duncan agrees.

“We’re confident that it’s the amount of water in the river that continues to drive the bus,” he says. “And we can work with water users to be as efficient as possible … But we can’t make snow. Ranchers are already taking voluntary cuts on the Big Hole, Beaverhead, and Ruby Rivers, and every one of those rivers could be dried up multiple times if it weren’t for their efforts.”

Marques adds that it’s important to look beyond the barbed wire fences to the roughly 2,800 square miles of mountainous country the Big Hole drains. He brings up the loss of beaver in the region, which has significantly reduced the landscape’s ability to hold water, along with the roughly 42 percent of rangeland that’s been lost to conifer encroachment over the last 30 years.

“If you ask the ranchers ‘where’s the water?’ they look up at the mountains,” Marques says. “These forests are overstocked. And every tree uses water: roughly eight to thirty-five gallons per lodgepole pine per day.”

Are Anglers Contributing to Trout Declines?

Marques also brings up a hard question that some anglers might not want to answer: Is there a chance that we’re part of the problem?

The ranchers in the Big Hole Valley have dealt with water shortages before. Both Marques and Duncan point to the drought of 1988, when the river went totally dry near Wisdom. Trout populations dipped as a result, but they say the ’88 crash still wasn’t as substantial as the one we’re seeing today.

“One thing to keep in mind is that agricultural practices in this valley—and the amount of water they use—haven’t changed substantially in 100-plus years,” Marques says.

One thing that has changed substantially is the amount of fishing pressure the Big Hole receives every summer. MFWP keeps track of this pressure by gauging the number of “angler days” in a year. (One “angler day” equals one angler fishing one body of water for any amount of time on a given day.) Past surveys by the agency showed 71,553 angler days on the Big Hole in 2011. That number jumped to 95,233 in 2017 and then to 118,140 in 2020, which equals a 65-percent increase over a nine-year period.

Floaters on the Madison River, which has also seen a huge increase in fishing pressure in recent years. BLM / Flickr

The question, then, is whether all this increased angling pressure is having a real impact on the fishery itself. Duncan can’t be certain it isn’t. Catch-and-release anglers have long seen themselves as having minimal to no impacts on wild fish populations. But the jury’s still out as to what percentage of trout survive, die, or get sick after they’re caught, handled, and released.

“We’ve seen a lot of increased pressure in recent years, just a lot more folks fishing on these rivers,” Duncan says. “And I think one of the reasons we’re interested in the impacts of catch-and-release angling is because it’s the one thing we have the most control over.”

These impacts can also vary depending on the waterway. It’s possible that some rivers in the West can handle more catch-and-release because there’s enough clean, cold water to keep fish populations healthy and strong in the first place. As an example, Marques points to the Madison River tailwater, which sees roughly three times the angling pressure at Big Hole.

Read Next: How a Dam Malfunction on the Madison River Nearly Wrecked a Blue-Ribbon Fishery

“People point to that river and say, ‘See, you can still hammer these fish as long as you release them—they’ll be fine.’ But that’s because the Madison has a dam that provides abundant cold water. I don’t think you can hammer these fish under certain situations. I think it adds a significant stressor to a fishery that’s already struggling.”

The most obvious stressor is the direct handling of fish, which can remove the protective slime that serves as a trout’s immune system. Playing fish for too long can also wear them down and make them more susceptible to predation or disease.

But there are secondary effects of angler pressure—more cars driving through the valley, more feet walking along the riverbed, and all the bug spray and sunscreen from 120,000 angler days—that could be impacting the river’s overall health and its bug populations. And fewer bugs means less food for trout.

Emergency Regs and Fishing Closures

While the state looks for answers, MFWP has enacted emergency fishing regulations on the Big Hole, Beaverhead, and Ruby Rivers. Catch and release is now mandatory throughout most of the Big Hole, as is fishing with single barbless hooks. The agency also plans to shut down fishing during the brown trout spawning season, which takes place in the fall. Duncan explains that browns are “extremely vulnerable” when they’re on their spawning redds—especially after dealing with low water conditions all summer.

These emergency regs are separate from the state-mandated Hoot Owl restrictions that are already in place on the Big Hole, Beaverhead, and Ruby Rivers. The restrictions close certain stretches to fishing after 2 p.m. and they’re triggered when water temps exceed 73 degrees for three days in a row. (You can find a list of the current closures and angling restrictions here.)

Other Things Anglers Can Do

“Right now, all the changes regulation-wise are being implemented on the fishing side of things,” Wheeler says. “And we have absorbed that happily because until we know, the outfitting community is willing to take these hits. We know we have to be extra cautious until we figure this out.”

Keep ’em wet. Andrew / Adobe Stock

For Wheeler and the other guides at Big Hole Lodge, this means carrying a thermometer and reeling up when water temps reach 68 degrees, which is even stricter than the state’s Hoot Owl rules. (Trout start to get stressed when water temps exceed 65, and they’re already struggling to survive by the time temps reach the mid-70s, according to Trout Unlimited.) It means keeping fish wet and handling them as gently as possible. It means staying off closed sections and not ripping browns off their spawning redds in the fall.

“These fish can be resilient when we figure out what’s happening and manage accordingly. But job number one is to define the problem,” Wheeler says. “That’s why I carry one of those coolers and aerators in my truck. And anytime I have a single fishing client, we’re bringing that in the boat with us and—I never thought I’d say this before—hoping to catch a sick fish.”

The post Trout Numbers Are Crashing in Montana, and No One Is Sure Why appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

By: Dac Collins

Title: Trout Numbers Are Crashing in Montana, and No One Is Sure Why

Sourced From: www.outdoorlife.com/conservation/montana-trout-declines/

Published Date: Fri, 04 Aug 2023 21:44:35 +0000

----------------------------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://manstuffnews.com/weekend-warriors/the-best-elk-hunting-gear-of-2023

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

Backyard GrillingWeekend WarriorsAdvice from DadBeard GroomingTV Shows for Guys4x4 Off-Road CarsMens FashionSports NewsAncient Archeology World NewsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions